In this ink-and-wash drawing, which was recently given to the J. Paul Getty Museum, two figures stand in a harrowing setting, surrounded by the heads of numerous submerged bodies. Giovanni Battista Paggi (1554–1627) represents a famous episode from Dante’s fourteenth-century poem The Divine Comedy, narrated at the end of Canto XXXII and at the beginning of Canto XXXIII of the Inferno. Dante, on the right, encounters a group of traitors in hell, who are trapped in the frozen lake of Cocytus as punishment. While walking with Virgil, he stops to question a few desperate souls, including Count Ugolino della Gherardesca, who is gnawing on the head of Archbishop Ruggieri degli Ubaldini. Ugolino, a former governor of Pisa who betrayed his citizens, recounts to Dante his tragic personal story in which he was imprisoned with his sons in a tower where they starved to death. This treacherous punishment was inflicted on Ugolino by Ruggieri, who then nominated himself governor of the city.

Paggi was born into the Genoese nobility, and, although he had to work around the restrictions imposed by the city of Genoa banning nobles from selling products and exercising any artisan profession, he started practicing the art of painting.1 In 1581 he fled his hometown to avoid prosecution after stabbing one of his patrons, and he arrived in Florence where he reached the peak of his artistic career. 2 In addition to receiving protection from the Medici court, he obtained commissions from the Grand Duke de’ Medici’s protégé Niccolò Gaddi (1537–1591), the Florentine families Segni and Pucci, Silvano Razzi (1527–1611)—an intellectual and member of the Accademia Fiorentina—and Bianca Cappello (1548–1587), Francesco I de’ Medici’s wife.3 His success in Florence and his familiarity with the Medici entourage ultimately favored Paggi’s inclusion in the Accademia del Disegno in 1591, which enhanced his status as a professional artist.4

Squared for transfer, the Getty drawing is preparatory for a now lost painting. A drawing at the Courtauld Gallery (fig. 1), which shows an almost identical composition, offers important information about the painting and clarifies the purpose of the Getty study. Conceived by Paggi as a ricordo, a visual record of one of his own works, the Courtauld sheet contains an inscription that reveals that the artist made the two-meter-wide painting in 1591 for Don Pietro de’ Medici, who was residing in Spain at the time.5 A letter by Pietro dated February 1592 attests that he was waiting to receive paintings from Florence in Madrid, making it plausible that Paggi’s work was sent with this shipment.6 While the Getty and the Courtauld drawn compositions closely correspond and the two sheets share approximately the same size, the Courtauld drawing is not squared, suggesting that it was not used in the design process, in keeping with its role as a ricordo. In comparison to the Getty drawing, in which Paggi captured the atmosphere and the setting through the use of dramatic wash, the Courtauld sheet is stylistically simplified. The contours of the figures are more clearly defined with pen and ink, and there are fewer submerged figures in the lake.7 As a result, the subject is much easier to read in the Courtauld sheet, with Ugolino’s mouth clearly agape while pausing from sinking his teeth into Ruggieri’s head, although it is lacking in the general intensity of the Getty drawing.

Paggi’s drawings and the related painting were created in response to renewed interest in Dante’s poem in the later sixteenth century. From the 1540s, regular readings and open lectures of the poem were held in Santa Maria Novella in Florence. Encouraged and supported by Duke Cosimo I (1519–1574), the readings and foregrounding of Dante’s The Divine Comedy were part of Cosimo’s political vision of promoting Florentine culture, language, and history.8 By the time Paggi executed the commission for don Pietro de’ Medici, several autonomous drawings from The Divine Comedy had been produced, including sheets made by Federico Zuccaro, Johannes Stradanus, and Jacopo Ligozzi,9 as well as paintings, such as one with an episode from the Purgatorio by Florentine painter Alessandro Allori,10 and four with moments from the Inferno attributed to Jacopo Ligozzi’s circle.11 The majority of these works have been linked to specific commissions for members of Florentine academies, which often promoted the reading and the publication of new editions of Dante’s verses.12 Paggi’s work was likely produced in a very similar context, given the role of its patron Pietro de’ Medici as the first protector of the Accademia della Crusca, a linguistic academy that aimed to standardize the Italian language following the literary works of Tuscan fourteenth-century authors, especially Dante.13

While Pietro de’ Medici’s involvement in the Accademia della Crusca can explain his interest in The Divine Comedy, the choice of the episode of Count Ugolino—a victim of betrayal—could have been driven by more personal motives. The early 1590s, when Paggi executed and sent the painting to Spain, were years of significant tension between Pietro and his brother, the Grand Duke of Florence, Ferdinand de’ Medici (1549–1609), and the city of Florence itself, since Pietro’s position in Spain and his eccentric lifestyle often troubled the delicate political relationship between the Grand Duchy and the Spanish crown.14 It is documented that, around 1591, Pietro prepared a manuscript for his sons containing all the attacks and false accusations made against him by Ferdinand, who, after Pietro’s death, promptly gave the order to burn all his documents.15

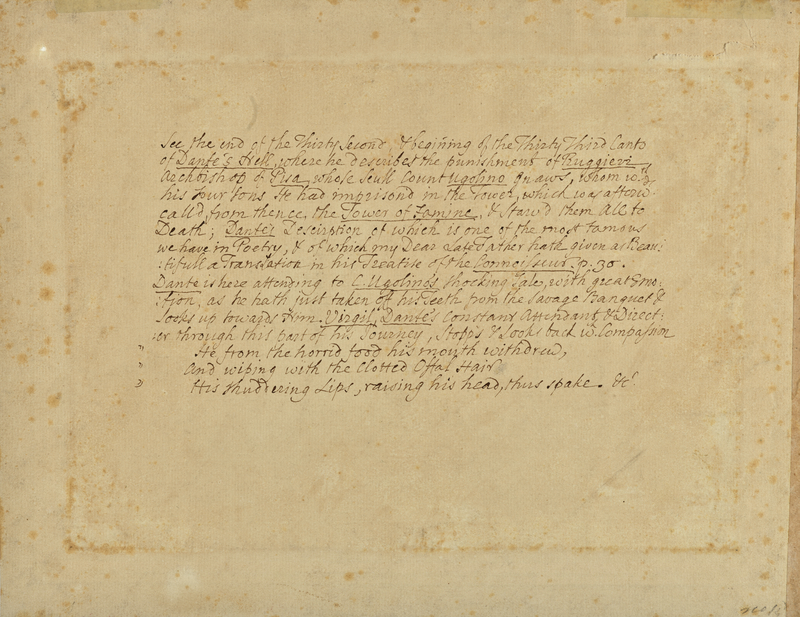

The afterlife of Paggi’s drawing is inextricably linked to its intense subject matter, as the sheet inspired considerable interest among later collectors for its treatment of Ugolino’s story.16 In an annotation on the verso of the mount of the drawing (fig. 2), the eighteenth-century collector Jonathan Richardson Junior (1694–1771), who owned the drawing and whose “R” mark is visible on the recto of the sheet, explains the episode of Dante’s Inferno and refers to an English translation of the passage by his father, the painter, connoisseur, and collector Jonathan Richardson Senior (1667–1745):

See the end of the Thirty Second, and beginning of the Thirty Third Canto / of Dante’s Hell, where he describes the punishment of Ruggieri / archbishop of Pisa, whose skull Count Ugolino gnaws, whom with / his four sons He had imprisoned in the Tower, which was after / called from thence, the Tower of Famine, and starved them all to / Death; Dante’s Description of which is one of the most famous / we have in Poetry, and of which my Dear Late Father hath given a Beau/tifull a Translation in his Treatise of the Connoisseur. p. 36. / Dante is here attending to C. Ugolino’s shocking tale, with great emo/tion, as he hath just taken off his Teeth from the savage Banquet and / looks up towards Him. Virgil, Dante’s constant attendant and direct/or through this part of his journey, stopps and looks back with Compagnon / ‘He from the horrid food his mouth withdrew, / and wiping with the clotted offal hair / his shuddering Lips, raising his head, thus spake.’

In his treatise on The Science of a Connoisseur, Richardson Senior uses Dante’s episode of Count Ugolino as the highest example of pathos and emotional intensity. The “shocking tale” narrated by Ugolino to Dante would have disturbed and moved the readers of Dante’s verses and, consequently, artists should endeavor to achieve the same intensity of feelings when depicting the scene. In his discussion on the comparison of the arts, Richardson imagines how the episode would have been represented by a painter and a sculptor, concluding that through the art of painting an artist could achieve the most complete and perfect work in terms of narrative, setting, and emotions.17 The inscription of Jonathan Richardson Junior highlights the dramatic component of the story represented and the gruesome detail of Ugolino suddenly removing his mouth from Ruggieri’s skull, an action that, following Dante’s contrapasso system of punishment, has been variously interpreted as an allusion to Ugolino eating the bodies of his dead children in the tower.18 The lack of any further details about the artist is unusual in Jonathan Richardson Junior’s annotations, which usually focus on connoisseurship and on the identification of the artist who made the drawing. In providing the reference to Dante’s passage, the inscription instead emphasizes how Paggi closely followed Dante’s emotional verses, creating a personal link with his father’s text, which contributed to a renewed interest in the story of Ugolino in eighteenth-century England.19

- Flavia Barbarini, J. Paul Getty Museum, Departments of Drawings

-

Peter Marshall Lukehart, “Contending Ideals: The Nobility of G.B. Paggi and the Nobility of Painting,” PhD. diss. (The Johns Hopkins University, 1988), pp. 27–29, 46–48. ↩︎

-

Mary Newcome, “Drawings by Paggi, 1577–1600,” Antichità Viva XXX, no. 4/5 (1991), p. 15. ↩︎

-

Lukehart 1988, pp. 50–51 and Pierluigi Carofano, “Appunti sull’attività Toscana di Giovan Battista Paggi,” in Honos alit artes. Studi per il settantesimo compleanno di Mario Ascheri, ed. Paola Maffei and Gian Maria Varanini (Florence: Florence University Press, 2014), pp. 189–190. ↩︎

-

Lukehart 1988, pp. 56, 88–101. ↩︎

-

“Al Sig.re D[on] Pietro Medici in Spagna – l’anno 1591 L bb.a 3 e ½.” ↩︎

-

Michael Brunner, Die Illustrierung von Dante Divina Commedia in der Zeit der Dante-Debatte (1570–1600) (Berlin, Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlad, 1999), p. 323, note 851. ↩︎

-

The Courtauld drawing’s relative dryness and the presence of a pen and ink line at the bottom of the composition are typical of Paggi’s ricordi drawings, as exemplified by another sheet in The Art Institute of Chicago (inv. 1922.1920). ↩︎

-

Mary Alexandra Watt, “The Reception of Dante in the Time of Cosimo I,” in The Cultural Politics of Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, ed. Konrad Eisenbichler (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2001), pp. 122, 128. ↩︎

-

Brunner 1999; De Girolami Cheney, “Illustrations from Dante’s Inferno,” pp. 488–520; Corrado Gizzi, Federico Zuccari e Dante, exh. cat. (Milan: Electa, 1993); Corrado Gizzi, Giovanni Stradano e Dante, exh. cat. (Milan: Electa, 1994); Robert L. McGrath, “Some Drawings by Jacopo Ligozzi Illustrating The Divine Comedy,” Master Drawings 5, no. 1 (Spring 1967), pp. 31–35, 86–89. ↩︎

-

Brunner 1999, pp. 327–328. Allori’s painting is now in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. ↩︎

-

Brunner 1999, pp. 302–304. The paintings attributed to Ligozzi’s circle were originally in the Drury-Lowe collection in Locko Park, England. Two paintings of the series, representing Dante and Virgil taking the ship with Charon to enter hell and Charon ferrying Dante and Virgil across the river Acheron, were offered at auction, Sotheby’s, Old Master Paintings, London, December 4, 2008, lot 171. ↩︎

-

The paintings by Ligozzi were made for Luigi di Piero Alamanni, a senior figure in the Accademia degli Alterati, an academy formed in 1569 where intellectuals gathered to discuss their writings and literary texts. Alamanni was also the owner of the Stradanus series, Brunner 1999, pp. 94–95. For the Accademia degli Alterati, see: Bernard Weinberg, “The Accademia degli Alterati and Literary Taste from 1570 to 1600,” Italica 31, no. 4 (December 1954), pp. 207–214; and Henk Th. van Veen, “The Accademia degli Alterati and Civic Virtue,” in The Reach of the Republic of Letters: Literary and Learned Societies in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. Arjan van Dixhoorn and Susie Speakman Sutch, 2 vols. (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2008), vol. 2, pp. 285–308. ↩︎

-

Volpini, “Pietro e i suoi fratelli. I Medici fra politica, fedeltà dinastica e corte spagnola,” Cheiron 53/54, no. 1/2 (2010), p. 140. ↩︎

-

Volpini 2010, especially pp. 159–160, and Edward L. Goldberg, “Artistic relations between the Medici and the Spanish courts, 1587–1621: Part I,” The Burlington Magazine 138, no. 1115 (February 1996), pp. 105, 113. ↩︎

-

Volpini 2010, 127, and Goldberg 1996, p. 114, note 68. ↩︎

-

The drawing has three collector’s marks, indicating part of its provenance history, belonging to Jonathan Richardson Junior (1694–1771, Lugt 2170); the English portrait painter Richard Cosway (1742–1821, Lugt 629), and the French collector Charles Molinier (1845–1910, Lugt 2917). ↩︎

-

Johnathan Richardson, Two Discourses. I. An Essay on the whole Art of Criticism as it relates to Painting. […] II. An Argument in behalf of the Science of Connoisseur […] (London: W. Churchill, 1719), pp. 30–35. ↩︎

-

Piero Boitani, “Ugolino dal Trecento al Rinascimento,” in Parlare dell’arte nel Trecento. Kunstgeschichten und Kunstgespräch im 14. Jahrhundert in Italien, ed. Annette Hoffmann, Lisa Jordan und Gerhard Wolf (Berlin; Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2020), pp. 31–42. ↩︎

-

Frances A. Yates, “Transformations of Dante’s Ugolino,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 14, no. 1/2 (1951), pp. 92–117. ↩︎