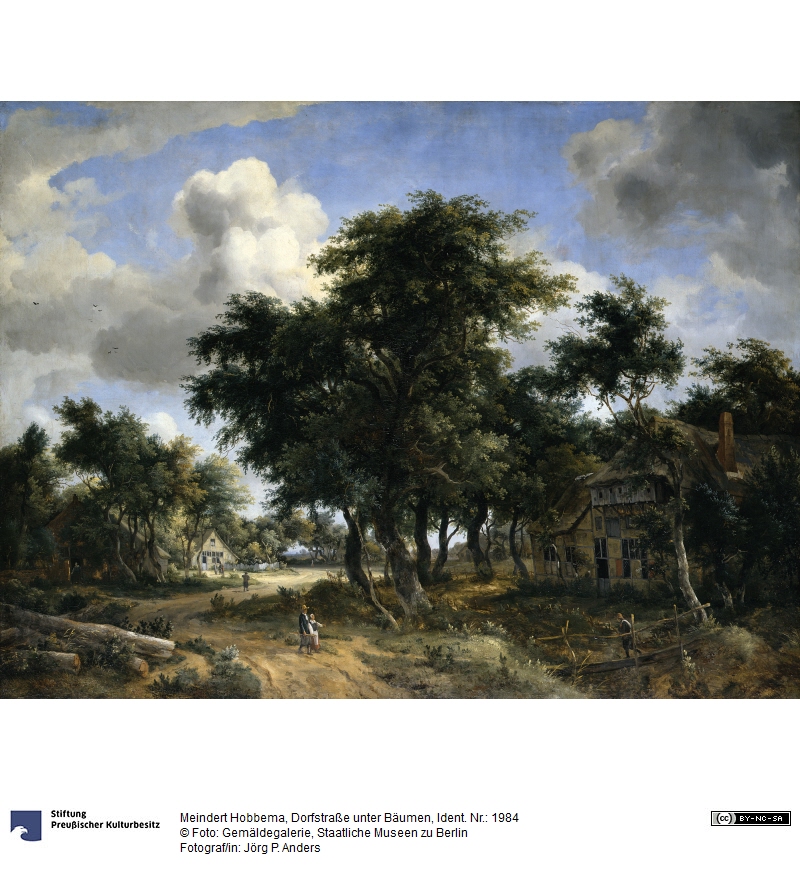

A few modest cottages nestled among trees serve as the unpretentious subject for one of Hobbema’s most beautiful grand-scale landscapes. Once part of a distinguished private collection from the mid-eighteenth to the late twentieth century, it is one of the artist’s least known but best preserved works. Monumental oaks cast the foreground into deep shade, which gives way to a gently rolling terrain of sunlit glades and leafy copses. Hobbema’s varied brushwork and nuanced palette of greens, browns, grays, and rosy tints impart a sparkling liveliness to the scene, extolling the textures of the oak trunks, young and mature foliage, weathered wood and brick. An elegantly clad horseman trotting along a muddy tract—its wet soil conveyed by thin, runny paint—invites the viewer to follow him past local denizens (both human and canine) toward a distant horizon. At right, a humbler path used by travelers and livestock meanders near an irregular brick house with a thatched roof. Swaying foliage, scudding clouds, and warm sunlight evoke the freshness of a breezy spring day in this accomplished canvas.

One of the most specialized Dutch landscape painters of the seventeenth century, Meindert Hobbema worked in Amsterdam, composing wooded scenes of tranquil village life, water mills, and ponds for an urban clientele. The son of Lubbert Meyndertsz, he later assumed the surname Hobbema for unknown reasons. Orphaned at an early age, Hobbema received his training under one of the greatest and most influential landscape artists of the period, Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/29–1682), who testified in 1660 that Hobbema had “served and learned with him for some years” (“bij hem eenighe jaren gedient en geleert”).1 It is highly likely that the two artists traveled together to the central eastern region of the Dutch Republic near the German border in the early 1660s.2 The countryside and rustic buildings, particularly the barns and watermills of Twente, Gelderland, and Overijssel, captivated Hobbema, who inventively reconstituted scenic elements from the region, along with motifs from Ruisdael’s oeuvre, in landscapes he composed afterward in his studio.3 Hobbema appears to have substantially curtailed his activities as a painter after 1668. In that year he married and assumed the lucrative position of a wine gauger to the Amsterdam octrooi (the body that levied taxes on goods brought into the city). Only a few works have been firmly attributed to him between 1671 and his late masterpiece, The Avenue at Middelharnis (1689; London, National Gallery)."4

Wooded Landscape with Travelers on a Path through a Hamlet dates from the mid-1660s, the apogee of the artist’s career. Whereas Hobbema’s paintings from the early 1660s still reflect Ruisdael’s influence in their dark palettes and closed compositions (fig. 1), those executed after 1663 exhibit a more expansive sensibility, freshness, and lack of rigidity, despite his reliance on a limited range of motifs. His greatest paintings are marked by a new spirited engagement with light and texture that distinguishes his pictorial style from Ruisdael’s formal stillness. In Wooded Landscape with Travelers, as in Village among Trees (1665; New York, Frick Collection) and Wooded Landscape with Cottages (ca. 1665; The Hague, Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis), sunlit spaces alternating with shady woods create a visual rhythm that animates his tranquil subjects.

In other large landscapes from about 1665, such as Village Street under Trees (fig. 2) and A Stormy Landscape (fig. 3), Hobbema employed a raised vantage point and low horizon similar to that found in Wooded Landscape with Travelers. Diverging pathways and double vanishing points were favorite means by which the artist encouraged the viewer’s eye to wander through the scene. While Hobbema generally employed a central axis or a tract beginning from the viewer’s right, Wooded Landscape with Travelers reverses the visual weight created by the deep areas of shadow from the left to the right foreground. As in A Stormy Landscape (fig. 3), in which the broad, reflective sweep of the river curves inward from the left, the main road in the present painting, in which a smaller body of water (a puddle) mirrors the sky, sweeps the eye toward distant reaches. Both the Wallace Collection and the Getty landscapes share similar compositions overall: tracts or a river coursing around the central stand of monumental trees, with buildings to either side. While the suggestion of impending foul weather in A Stormy Landscape provides a subtle contrast to a sunnier mood of the present picture, it does not disrupt Hobbema’s generally congenial presentation of nature. Wooded Landscape with Travelers and the nearly two dozen large-scale landscapes from about 1665 may constitute a loosely conceived series of magisterial and complementary compositions. Much remains to be learned about Hobbema’s patrons and marketing of his works, but smaller paintings, such as the Getty’s A Wooded Landscape (1667) may have been produced for the open market. Perhaps painted on commission due to its grand scale, Wooded Landscape with Travelers and other landscapes of similar dimensions dating from the mid-1660s are among Hobbema’s most distinctive contributions to the genre.5

While Hobbema often painted his own staffage, he occasionally employed other artists in this capacity, such as Nicolas Berchem (1620–1683) and Johannes Lingelbach (1622–1674), in keeping with contemporary practice. As John Smith first noted, Abraham Storck (1644–1708), a capable painter of small marine and seaside genre scenes, was responsible for the array of figures in Wooded Landscape with Travelers.6 Storck’s skillful characterization of diverse types (including minute details such as the clay pipe held by the man at far left), along with his distinctive viscous application over the finished landscape elements, compliments Hobbema’s own descriptive brushwork.

Nothing is known of Hobbema’s studio practice. However, the confident and energetic brushwork in this painting suggests that he composed his subjects directly on the canvas according to a well-established process.7 A few small pentimenti are visible to the naked eye, revealing Hobbema’s fine-tuning of the rhythm of the elements in the scene. Notably, Hobbema painted over a few of the slats in the fence around the barn (at left; fig. 4) to create a gap that suggests dilapidation as well as an area of greater visual interest. Storck also made alterations to the figures while he was painting; for example, the hat of the man at left was made smaller.

Along with Salomon van Ruysdael (1600/03?-1670) and Philips Koninck (1619–1688), Hobbema’s landscapes epitomize the native Dutch landscape tradition. While it is difficult to ascertain the connotations his lush scenes may have held for his early patrons, Hobbema’s pleasant wooded landscapes may have offered seventeenth-century viewers a subject as alluring as the mountain views and golden skies of the Dutch Italianate painters. The eastern provinces of the Dutch Republic were remote and unfamiliar to most residents of Amsterdam—representing, in essence, a Dutch “outback.” The Haarlem painter Vincent Laurensz. van der Vinne (1628–1702) traveled through the region in 1652 and described the topography of Gelderland in his diary: “It is a flattish land with few mountains, but amusing with less profitable woods. . . . The soil is usually fruitful, especially for wheat and buckwheat and in some places (mostly around the Maas, Waal, and Rijn [rivers]), very grassy and suitable for cattle, of which many were grazing there.”8 The gray, weathered wood barn at left and brick houses with thatched roofs in Wooded Landscape with Travelers identify the setting as the region on the border with Germany. Travelers on horseback and on foot, and deep ruts alluding to wheeled carriage traffic, are a visual convention with a long history in Northern painting. They invite the viewer to traverse the countryside and look closely at its features and charming details, such as the cat sitting on the split door of the cottage at right.9 Landscape views with scenic motifs in the form of great trees and rustic buildings imparted a sense of contentedness. Hobbema’s cheerful view of nature may also have offered a connection to a timeless and indigenous way of life to city dwellers.

Wooded Landscape with Travelers attained new significance when it was acquired by the preeminent collector of Dutch and Flemish paintings in Britain, John, 3rd Earl of Bute (1713–1792) in the mid-eighteenth century. A friend and mentor of Frederick, Prince of Wales, later George III, he served as adviser, Secretary of State (1761), First Lord of the Treasury (1762), and, finally, de facto Prime Minister, wielding great authority in statecraft before retiring from politics in 1763 as an unpopular figure frustrated by political disappointments. A distinguished arbiter of taste, Lord Bute had guided the education of the young Hanoverian prince and later continued to influence the formation of the royal collection.10 His education at the University of Groningen and the University of Leiden (1730–34) evidently profoundly influenced his own interests in art.11 With the assistance of the energetic etcher and dealer Captain William Baillie (1723–1810), among others, he quickly formed the most outstanding collection of Dutch and Flemish paintings in England. Beginning modestly at first in 1749, he assembled a range of important works by Jacob van Ruisdael, Aert van der Neer (1603–1677), and Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684), as well as a remarkable group of landscapes by Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691).12 Wooded Landscape with Travelers was probably obtained during the early 1760s, perhaps as part of a heady buying phase in the autumn of 1762.13 Bute’s small but important group of Dutch landscapes by Hobbema, Ruisdael, and Berchem placed him well ahead of avid British taste for Dutch landscapes which peaked only about eighty years later.

Hobbema’s Wooded Landscape with Travelers hung at Bute’s Bedfordshire estate, Luton Park, designed by Robert Adam in the early 1770s. The Neoclassical house was surrounded by a great park landscaped by Lancelot “Capability” Brown starting in 1765.14 Lord Bute was a keen naturalist and observer of nature with a penchant for trees, and Hobbema’s pleasantly arranged Dutch countryside may have resonated with him as strongly as Brown’s concurrent genial manipulation of the English landscape. A Wooded Landscape with Travelers was probably the Hobbema painting seen and recorded at Luton by Brownlow Cecil, the 9th Earl of Exeter in 1776, 15 and is also probably the work mentioned in the first catalogue of the collection drawn up in about 1799, when it was located in the anteroom to the library “opposite the chimney”: “Hobbima [sic] a landscape—very fine.” John Smith considered it a “capital picture [that] possesses in the highest degree the various beauties for which this distinguished master’s works are esteemed,” while Gustav Waagen declared: “In lighting, delicacy of aerial perspective, power and truth of effect, as well as in size . . . a capital work by the master.”16 Though it was regularly exhibited by the marquesses of Bute in the late nineteenth century following a fire at Luton, Wooded Landscape with Travelers remained out of the public view for most of the twentieth century and was consequently overlooked by scholars.17 A painting in superb condition, it retains the textural crispness and luminosity of Hobbema’s most notable works.

- Anne T. Woollett

-

Abraham Bredius, “Nog een ander over Hobbema,” Oud Holland 33 (1915), p. 193–94; H. F. Wijnman," Het Levens der Ruysdaels, II," Oud Holland 49 (1932), p. 194. ↩︎

-

Seymour Slive, Jacob van Ruisdael: Master of Landscape, exh. cat. (Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Philadelphia Museum of Art; London, Royal Academy of Art, 2005), p. 5. ↩︎

-

For the journey to the eastern provinces, see E. John Walford, Jacob van Ruisdael and the Perception of Landscape (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), pp. 9, 121, 123, 125–27. Only a few drawings have been attributed to Hobbema, including five sketches of watermills. See Jeroen Giltay, “De tekeningen van Jacob van Ruisdael,” Oud Holland 44 (1980), pp. 141–208. ↩︎

-

For Hobbema’s career, see Wolfgang Stechow, Dutch Landscape Painting of the Seventeenth Century (London: Phaidon, 1966); Peter C. Sutton, ed. Masters of 17th-Century Dutch Landscape Painting, exh. cat. (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts; Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1987), pp. 345–54. ↩︎

-

Measuring approximately 98 x 130 cm, the group includes: Village Street under Trees, ca. 1665 (Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, inv. 1984); Wooded Landscape with a Pool and Watermills, ca. 1663–68 (Cincinnati, The Taft Museum, 1931.407); Wooded Landscape with Cottages, ca. 1665 (The Hague, Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, inv. 1105); Village among Trees, 1665 (New York, Frick Collection, 1902.1.73); A Wooded Landscape, 1663, and A View on a High Road, 1665 (Washington, DC, National Gallery of Art, 1937.1.61, 1937.1.62); Cottages in a Woodland Clearing with a Young Fiddler Arriving Home in a Cart Greeted by his Family, ca. 1665 (Baron von Dedem). ↩︎

-

John Smith, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters, vol. 6 (London: Smith and Son, 1835), p. 151. Also Gustav Friederich Waagen, Treasures of Art in Great Britain, vol. 3 (London: John Murray, 1854), p. 481. For Storck, see A. Houbraken, De Groote Schouburgh (Amsterdam, 1718–21), vol. 3, p. 255; I. H. Van Eeghen, "De schildersfamilie Sturck, Storck of Sturckenburch,"Oud Holland 68 (1953), pp. 216–23. ↩︎

-

For an overview of the workshop practice of seventeenth-century Dutch landscape painters, see David Bomford, “Techniques of the Early Dutch Landscape Painters,” in Dutch Landscape: The Early Years, Haarlem and Amsterdam, 1590–1650, exh. cat, ed. Christopher Brown (London, National Gallery, 1986), pp. 45–56; Sutton 1987 (note 4), pp. 5–8. ↩︎

-

“Tis een vlack achtich lant met weijnich bergen, maer vermakelijcke en met min proffitelijke bosschaeijen,onder and’re het bos Echter wald, leggende noortwest van Aernem. De grond isser doorgaens vruchtbaer, insonderheijt van kooren en boeckwijt en op sommige plaatsen (doch meest ontrent Maes, Wael en Rijn) seer gras-rijck en bequam voor het vee, dat met menichte aldaer wert geweijdet,” see Dagelijkse aantekeningen van Vincent Laurensz van der Vinne. Reijsjournaal van een Haarlems schilder, 1652–1655, introduced and adapted by Bert Sliggers Jr. (Haarlem: Fibula-Van Dishoeck, 1979), p. 48. ↩︎

-

The practice of undertaking a visual journey or even pilgrimage through a landscape may derive from fifteenth-century Flemish painting, notably the work of Hans Memling. ↩︎

-

See particularly Francis Russell, John, Third Earl of Bute: Patron and Collector (London: Merrion Press, 2004). ↩︎

-

Russell 2004 (note 10), pp. 4–5, 183. ↩︎

-

Pieter Fouquet, the prominent dealer of Dutch paintings, may also have procured paintings for Bute, for which see Russell 2004 (note 10), pp. 190–91. River Landscape with Horsemen and Peasants is today in the collection of the National Gallery, London (inv. 6522 ). ↩︎

-

Although it has not been possible to determine when and from what source Bute acquired the Landscape with Travelers, he spent a substantial amount on pictures from Holland in 1762, for which see Russell 2004 (note 10), pp. 184–85. The painting was already in his collection at Luton Park by 1776, when it was seen there by the earl of Exeter. See note 15. Bute was also an avid collector of Italian masters, including large works appropriate to display in state rooms and in line with erudite collecting practices more generally. ↩︎

-

See Russell 2004 (note 10), pp. 167–70. ↩︎

-

The earl of Exeter’s notes are contained in an interleaved copy of Pellegrini Antonio Orlandi, Abecedario Pittorico (Venice: Pasquali, 1753), 2 vols. (Burghley House, Lincolnshire), “A Landscape by Mindehout Hobbima at Luton”; Susan Morris in Art Without Borders: European Old Master Paintings, 1600–1820 (London: Richard Green, 2002), p. 171. ↩︎

-

Smith 1835 (note 6), p. 151; Waagen 1854 (note 6), p. 481. ↩︎

-

For example, it was not included in catalogue raisonné by Georges Brouliet, Meindert Hobbema (1638–1709) (Paris: Firmin-Didot et Cie., 1938). Ellis Waterhouse noted a Hobbema in the residence of the 4th Marquess of Bute (15 Mansfield Street) on July 26, 1934. However, that work, which he described as “his [Hobbema’s] typical & deplorable piece of regular greenery—neither in any way outstanding,” was more probably A Watermill, a smaller work by Hobbema (Smith 1835 [note 6], no. 102); Ellis Kirkham Waterhouse notebooks and research files, 1801–1987, bulk ca. 1924–ca. 1979, Getty Research Institute, Research Library, accession no. 870204, Notebooks, 1931–1935, folder 10, p. 47. ↩︎