Finely detailed yet majestic in its scope, Landscape with the Temptation of Saint Anthony is Roelandt Savery’s most impressive forest landscape dating from his brief Amsterdam period (1613–19). Unusually well preserved, it evinces a sophisticated dialogue between remote alpine topography and the trials of isolation suffered by a popular hermit saint. The thickly wooded terrain unfurls across the horizontal composition, revealing a series of distinct prospects, from dark, dense undergrowth at the far left, to a sparking cascade and a lofty stand of trees in the center, to a luminous distant vista at right. Rays of sunlight burst forth over looming rock formations and a rushing river that cascades over boulders and winds through imposing trees to plunge again toward a faraway plain. Nestled unobtrusively in the lower left corner among the shrubbery, the hermit saint Anthony the Great sits in his rustic wooden cell, his faithful pig slumbering at his feet. Absorbed in his Bible and holding a crucifix, he is as oblivious to the magnificence of his remote retreat as to the antics of the assorted fantastic demons that harass him. Numerous forest animals and birds, notably mountain goats, deer, and cranes, populate the scene.

Savery returned to the Netherlands in 1613 after nine years spent in Prague as court painter to the Holy Roman emperors Rudolf II (reigned 1576–1612) and Matthias (reigned 1612–19). While at court, he specialized in landscape, still-life, and animal subjects, joining other leading Dutch and Flemish artists, such as Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1601) and Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625), in the innovative elucidation of natural subjects that were Rudolf’s particular delight.1 At the behest of Rudolf II, Savery undertook a journey through the rugged Bohemian and Tyrolean Alps in 1606–7, becoming one of the earliest artists to draw the spectacular terrain of the isolated alpine wilderness.2 He captured steep mountainsides covered with thick pine forests, massive boulders, and rushing waterfalls on paper, reworked them in the studio, and then later adapted them into reimagined painted landscapes of fresh, wild power. Smaller, more intimate motifs were published as prints by Aegidius Sadeler II (ca. 1570–1624).3 Upon his return to the Netherlands, Savery was lauded by poets as a “light” of Amsterdam and, specifically, as a painter of landscapes, a designation that attests to the admiration his work received in the metropolis.4 The artist’s landscape forms became even more monumental after he moved to Utrecht in 1619, dwarfing religious subjects still further (for example, Landscape with the Flight into Egypt, 1624, Washington, DC, National Gallery of Art). From this time until his death, Savery’s vigorous production, aided by his studio, concentrated on flower pieces and popular, encyclopedic menageries.5

Savery’s own exceptional exposure to rugged alpine terrain fundamentally shaped his innovative approach to landscape. While continuing to employ the detailed and decorative handling of late-sixteenth-century painters highly regarded by his patron, such as Pieter Brueghel the Elder (ca. 1525/30–1569), Hans Bol (1534–1593?), and Gillis van Coninxloo (1544–1607), Savery composed his expansive scenes by adopting a more direct, frontal viewpoint and including still-unusual elements he had studied first-hand, such as tumbling cascades and vertiginous slopes.6 Dramatic light effects, achieved through the juxtaposition of darker foreground features and a brighter middle ground, and occasionally even brilliant rays of light (in the upper left) served to enhance the spectacular nature of the painting. Though based on observation, Savery’s minutely detailed natural settings were ultimately fantastic creations devised in the studio. The isolated majesty of views such as Landscape with the Temptation of Saint Anthony would have delighted urban dwellers with their novelty. Savery’s alpine subjects helped to generate a new taste among patrons for powerful landscape forms and laid the foundation for the heroic landscapes of the mid-seventeenth century by Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/29–1682), Allart van Everdingen (1621–1675), Gillis d’Hondecoeter (1575?–1638), and Esias van de Velde (1587–1630).

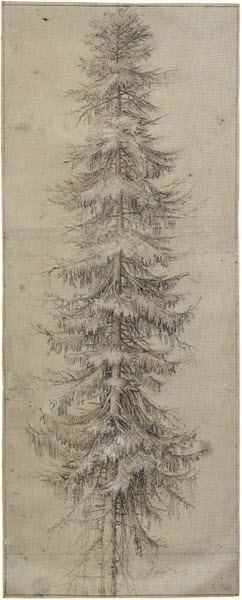

While Savery had depicted specific landscape elements, such as waterfalls and dense woody undergrowth, in small-scale paintings when residing in Prague, he united various constituents into unified compositions upon his return to the Netherlands.7 As in the present work, a number of his paintings from the second decade adopt a strong lateral shift and move from a near view to a sweeping blue vista that recalls sixteenth-century Flemish landscape formulas. Savery’s expansive scenes were enhanced by the use of a double-width horizontal format anchored by a strong vertical feature at the center, such as a centrally placed tree or a ruin, as in The Drink, ca. 1616 (Kortrijk, Museum voor Schone Kunsten).8 Savery’s fascination with striking trees is borne out by several drawings of single firs in various media (fig. 1).9 One of the most captivating elements of the present work, the golden fir in the middle ground with delicate, animated foliage, has its antecedents in Savery’s Prague-era compositions, such as Forest Landscape with a Waterfall and Deer in Bohemia (Dalfsen, Gräfin van Regteren-Limpurg-van Lynden; fig. 2)—a wilder precedent for the composition of the present work…10 In Landscape with the Temptation of Saint Anthony, the foreground vignette of goats gathered among dainty ferns at the base of the central fir invites the eye to explore the landscape.

In this work, in which Saint Anthony’s presence is surprisingly inconspicuous, the wilderness and the solitude it represents are the true subjects of the painting. During the course of the sixteenth century, the portrayal of popular hermit saints who had retreated to the desert, such as Jerome and Anthony, in broad, “world” landscapes became widespread, following the compositions of Joachim Patinir (ca. 1480/85-1524) and Herri Met de Bles (ca. 1510)—artists whose brilliant panels were avidly collected by Habsburg princes. However, as the present work demonstrates, Savery was also attuned to current developments in the circles of the Flemish painters Paul Bril (ca. 1554–1626) and Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625). Working in Rome in the 1590s for Counter-Reformation patrons including Cardinal Federico Borromeo, Bril and Brueghel produced luminous, small landscapes on copper with rustic hermitages tucked into foreground corners. Landscape with the Temptation of Saint Anthony, Savery’s only depiction of the temptation of Saint Anthony, recalls the Mountain Landscape with Saint Anthony from the well-known series Solitudo, sive vitae partum eremicolarum designed by Marten de Vos, engraved by Jan and Raphael Sadeler (ca. 1588; fig. 3), and subsequently painted by Jan Brueghel the Elder.11 In his related portrayals of Saint Jerome, Savery integrated the hermit saint into the terrain even more thoroughly than Bril and Brueghel, almost camouflaging his presence amid rocks and branches.12 The saint’s monstrous tormentors recall the fantastic creatures of Hieronymous Bosch (ca. 1450–1516), which were disseminated through the graphic work of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and remained extremely popular well into the seventeenth century.13 Savery’s fantastic beasts, like the long-tailed creature flying from the direction of the cascade (fig. 4), appear almost as natural denizens of the scene.14

Even more than his Flemish predecessors, however, Savery expounded on the magnificence of the wilderness to underscore the hermit saint’s total retreat from civilization. According to the Legenda Aurea, Anthony the Great, the father of monasticism and the vita contemplativa, sought sanctuary in the mountains.15 There, in the metaphorical desert, the steadfastness of his faith was challenged as he was subjected to hallucinatory attacks by fiends. Savery’s exquisitely detailed natural setting amplified the central themes of Anthony’s legend: solitude, separation from worldly goods, and comfort in nature. By situating the quintessential subject of an ascetic existence in the depths of one of Europe’s most fascinating but remote locations, Savery celebrated the contemporary view, most extensively demonstrated by Rudolf II’s collecting and patronage, that the wonders of nature are evidence of God’s creative power.

- Anne T. Woollett

-

Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, L’école de Prague: La peinture à la cour de Rodolphe II (Paris: Flammarion, 1985), pp. 114–28; Lee Hendrix, “Natural History Illustration at the Court of Rudolf II,” in Rudolf II and Prague: The Court and the City, exh. cat., eds. Eliška Fučícová et al. (Prague: Prague Castle Administration; London, New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997), pp. 157–71. ↩︎

-

According to Sandrart, Savery was sent to draw the “unusual wonders of nature” (Joachim Von Sandrart, Teutschen Academie II, book 3 [Nuremburg, 1675], p. 305 [TA 1675, vol. 2I, Buch 3 (niederl. u. dt. Künstler), S. 305, http://ta.sandrart.net/531]); Joaneath Spicer-Durham, “The Drawings of Roelandt Savery,” (PhD diss., Yale University, 1979), pp. 51–62. Rembrandt van Rijn acquired one of Savery’s alpine notebooks, described as “Een ditto [een bookie], groot, met teeckenige in 't Tirol van Roelant Saverij nae 't leven geteeckent,” in the inventory of Rembrandt’s effects drawn up July 25–26, 1656, for which see Walter L. Strauss, and Marjon Van der Meulen, with the assistance of S. A. C. Dudok van Heel and P. J. M. de Baar, The Rembrandt Documents (New York: Abaris, 1979), p. 377, no. 270 (fol. 36). ↩︎

-

F. W. H. Hollstein, Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings, and Woodcuts, ca. 1450-1700. 72 vols. (Amsterdam: M. Hertzberger, 1949–2010). Aegidius Sadeler to Raphael Sadeler II: text comp. Dieuwke de Hoop Scheffer, ed. K. G. Boon (Amsterdam: Van Gendt & Co., 1980), vols. 21, pp. 46–51, vol. 22, pp. 48–61. ↩︎

-

Balthasar Gerbier, Eer ende de Claeght-Dicht: Ter Eeren van de lofweerdighen constrijcken ende gheleerden Henricus Goltzius . . . 1617, (The Hague: Aert Meurs, 1620); see Otto Hirschmann, “Balthasar Gerbiers Eer end Claght-Dight ter Eeren van Henricus Goltius,” Oud Holland 38 (1920), p. 111; for the praise of Theodore Rodenburgh (1618), see N. De Roever, “Drie Amsterdamsche Schilders (Pieter Isaaksz., Abraham Vinck, Cornelis van der Voort),” Oud Holland 3 (1885), p. 172. ↩︎

-

For Savery’s career, see Kurt J. Müllenmeister, Roelant Savery: Kortrijk 1576–1639 Utrecht, Hofmaler Rudolf II in Prag: Die Gemälde mit kritischem Œuvrekatalog (Freren: Luca Verlag, 1988). ↩︎

-

Joaneath Spicer, “Roelandt Savery and the ‘Discovery’ of the Alpine Waterfall,” in Rudolf II and Prague: The Court and the City, exh. cat., eds. Fučícová, Eliška. et al. (Prague: Prague Castle Administration; London, New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997), pp. 146–56. ↩︎

-

Prague-era works include, for example, Mountain Landscape with a Cascade and Forest Landscape with a Hermitage, Hannover, Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum, no./s KA 154/1967 and VAM 933; see Müllenmeister 1988 (note 5), pp. 210–11, cats. 47 and 46. ↩︎

-

Müllenmeister 1988 (note 5), p. 278, cat. 169. ↩︎

-

For Savery’s drawings see Spicer-Durham 1979 (note 2), especially C49–53. ↩︎

-

Oil on panel, 49 x 88 cm; see Müllenmeister 1988 (note 5), pp. 223–24, cat. 65. ↩︎

-

Christiaan Schuckman, comp., Marten de Vos. 3 vols.; F. W. H. Hollstein, Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings, and Woodcuts, ca. 1450–1700., ed. D. de Hoop Scheffer, (Rotterdam: Sound & Vision in cooperation with Amsterdam: Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum, 1995), vols. 44, p. 204, no. 966; vol. 46, part 2, p. 68; Pamela Jones, Federico Borromeo and the Ambrosiana: Art Patronage and Reform in Seventeenth-Century Milan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 131, 134. ↩︎

-

For Savery’s treatments of Saint Jerome, see Müllenmeister 1988 (note 5), pp. 151–52, 313–18. ↩︎

-

Both Roelandt and his elder brother Jacob were among the preeminent artists perpetuating the popular motifs and compositions of Pieter Bruegel the Elder around 1600. An enthusiastic admirer of Pieter Bruegel’s art, Rudolf II possessed an extraordinary collection of his paintings including, significantly, the mountainous Conversion of Saint Paul (1567; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum), which features a rocky high mountain pass and an imposing stand of bristling firs. (Joaneath Spicer, “The ‘Naer het Leven’ Drawings: By Pieter Bruegel or Roelandt Savery?,” Master Drawings 8 [Spring 1970], pp. 3–30). ↩︎

-

Although several of the fantastic fiends in Landscape with the Temptation of Saint Anthony resemble the Boschian creatures in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s print series The Seven Deadly Sins (1556–58), Savery may also have had access to drawings by Bruegel while in Prague. See Martin Royalton Kisch, “Pieter Bruegel as Draftsman: The Changing Image,” in Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Drawings and Prints, exh. cat., ed. Nadine Orenstein, (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), p. 32; for Bruegel’s print series, see Jürgen Müller in ibid., pp. 144–60, cat. 42–54. ↩︎

-

Jacobus De Voragine, The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. 2 vols., trans. William Granger Ryan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), vol. 1, pp. 93–96. ↩︎