In this rediscovered portrait by Anton Raphael Mengs, the German painter depicted his friend, the Spanish diplomat José Nicolás de Azara (1730–1804), Marquis of Nibbiano, in three-quarters’ profile, seated at a wooden table, an index finger inserted into a book as if he had been interrupted while reading. Elegantly but simply dressed, Azara is wearing a deep blue justacorps with wide flaps, a yellow vest with red trim, and a white shirt, open at the collar. His brown hair is worn naturally, slightly curled in bobs above the ears, and his facial features are rendered with close attention to individualistic detail, including a broad forehead, fleshy neck, and dimpled nose. The portrait is one of many that Mengs produced for European aristocrats and dignitaries, who prized the artist’s disciplined compositions, refined brushstrokes and vibrant palette. But it also marks a notable shift in his approach to portraiture and documents an intriguing relationship between artist and sitter that had an enduring impact on the history of European art and collecting.

Mengs was one of the most acclaimed painters in Europe in the late eighteenth century and an early proponent of the Neoclassical manner that would come to dominate European artistic production by the turn of the nineteenth century.1 Born in Aussig, a Bohemian city near Dresden (now Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic), Mengs made several early pilgrimages to Rome to study antique sculpture and the Renaissance and Baroque masters. He would go on to pursue an exceptionally cosmopolitan practice in both Rome and Madrid, where he served for nearly a decade, from 1761 to 1769, as court painter to King Charles III of Spain (1716–1788).2 Mengs’s largest projects were ceiling paintings, at the Palacio Real in Madrid (1762–1769; 1775), the ballroom of the Villa Albani in Rome (1760–1761), and in the Camera dei Papiri in the Vatican Library (1772–1773), but he was most accomplished as a portrait painter. His portraits of court figures, such as the Bourbons in Naples and Habsburgs in Madrid, were often a riot of colors and textures, capturing the trappings and opulence of court life. In Rome, he established a studio in the former home of the French painter Pierre Subleyras (1699–1749), and like his principal rival Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787), he pursued commissions from aristocrats and visiting dignitaries on the Grand Tour of Italy’s cultural monuments.3 Compared to his court portraits, many of these pictures are restrained, combining classical moderation with select rhetorical details. By the time he painted Azara, Mengs’s portraits were notable as much for their versatility and inventiveness as for their rich colors and compositional refinement.

Mengs seems to have encountered Azara for the first time in 1765, when the artist was recruited to assist in the design of a medal to commemorate the engagement of the Prince and Princess of Asturias.4 Born to a wealthy Aragonese family, Azara played an important diplomatic role in the court of King Charles III of Spain. In the mid-1760s, he was appointed General Agent and Procurator in the Papal States and moved to Rome, where he built a network of prominent politicians, artists and writers. Mengs’s and Azara’s friendship was forged through a shared interest in the classical world, fueled by the writings of their mutual friend, the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768).5 Azara’s engagements with classical art and literature were multi-fold, as publisher, archaeologist and collector.6 He collaborated in the publication of new translations of classical texts, including Horace, Virgil and Catullus, led excavations of Roman ruins at Tivoli, and amassed a sizeable collection of portrait busts and cameos, the latter of which would enter the collection of King Charles IV (1748–1819). Most famously, he unearthed a herm and bust of Alexander the Great, for a time the only known portrait of the Macedonian conqueror.7

Azara enlisted Mengs as an occasional collaborator in these projects. According to Azara, it was Mengs who recognized the bust of Alexander the Great for what it was, later confirmed by the discovery of an inscription nearby.8 Azara commissioned Mengs to design a series of engravings depicting the recently excavated Villa Negroni in Rome, and at times served as an intermediary between Mengs and his royal patron in Madrid. For his part, Mengs’s theoretical musings on art and beauty were undoubtedly influenced by discussions with his friend, and by the archaeological record that Azara amassed during their overlapping years in Italy. The depth of their friendship is evident in Azara’s biography of Mengs, published the year following the artist’s death, where he wrote unsparingly but with empathy about Mengs’s obsessive work ethic, tortured relationship with his father, and deep affection for his wife and children.9 In recounting Mengs’s decline and death, which he attributed to a combination of overwork, self-neglect and medical malpractice, Azara’s grief is palpable. “I confess that my feelings suffer much at the remembrance of the sad scene, for which reason I will give but a short account of that doleful tragedy.”10 The loss of his friend seems to have been almost too painful for Azara to put into writing.

Mengs painted at least two portraits of Azara: a version on panel that entered the collection of the Prado Museum in 2013 (fig. 1), and the newly rediscovered Getty version, which is on canvas.11 As Azara explained in his biography of Mengs, the Prado portrait was painted in 1773–1774, when artist and sitter crossed paths in Florence while the latter was returning from a diplomatic mission to Parma.12 Because they had so little time together, Azara’s hand in the Prado portrait was not modelled on his own, but instead on that of a later sitter, the composer Johann Gottlieb Naumann (1741–1821). Since the hand in the Prado and Getty paintings are identical, it seems likely that the Getty painting was based on the original Prado picture rather than produced during a separate sitting.13 While the circumstances of the production of the Getty version are not documented, Steffi Roettgen has speculated that it may have been created for Azara to gift to a longtime lover, Giuliana Falconieri (1748–1814), a member of Rome’s high society who married Prince Antonio Publicola Santacroce in 1767.14

The portrait of Azara is notable for its pleasing correspondences: Azara’s open collar and the open book; the ripples in Azara’s shirt and the ripples on the table’s wood surface; and the brilliant red trim of his waistcoat taken up again in the book’s edge-painting. In formulating the picture, Mengs drew on his close study of the Renaissance masters. The formal composition recalls Raphael, while areas of chiaroscuro and rich color, applied in relaxed brushstrokes down the front of Azara’s chest, suggest the importance of Correggio and Titian to Mengs’s development. In his notes accompanying the publication of Mengs’s handbook for painters, Reflections upon Beauty and Taste in Painting, Azara argued that Mengs’s particular skill derived from his ability to harness the best of each of these Renaissance antecedents: Raphael for his design and expression, Correggio for his grace and chiaroscuro, and Titian for coloring, which together appealed to the full range of the viewer’s faculties: to the head, the heart and the eye.15 Mengs also adopted visual strategies to flatter and humanize his friend. Despite the composition’s prevailing grays and blues, light illuminates Azara’s broad forehead and hand, linking the physical loci of knowledge to the means by which it is disseminated, and calling subtle attention to Azara’s expansive intellect and literary pursuits.

Scholars have noted a shift in Mengs’s portraiture around the time he painted Azara toward a more informal approach that emphasized an intimacy between the artist, viewer and subject.16 For example, in his portrait of Cardinal Francesco Saverio de Zelada (1717–1801) (fig. 2), begun in Rome in 1773 but finished in Florence the following year, Mengs subverted the traditional grandeur and reserve of the ecclesiastical portrait by depicting Zelada with mouth open and a wry smile on his face, as if he were responding to a jest by the portraitist.17 Zelada was one of the most powerful men in Rome at the time, but Mengs made him seem accessible, casually holding his red cap in his right hand, his mantle obscuring the more intricate finery of his lace vestments. Mengs achieved a similar intimacy in his portrait of Azara, imbuing his subject with great psychological depth and complexity. In addition to adopting a more casual rhetoric in manner and dress, Mengs depicted with great subtlety how the eyes divulge character. The heavy upper lid and the under-eye shadow, with its hint of puffiness, suggest a fatigue born of hard work and discipline, while the moisture welling up near his tear duct, shimmering in the light, captures something of the warmth and tenderness he felt for his friend. Azara, hardly an unbiased critic, attributed the portrait’s success to an additional element: the strength of their affection for one another. Recalling their brief time in Florence when the Madrid panel was executed, Azara wrote that “[Mengs’s] friendship for me made him perform wonders in the execution.”18

The portrait of Azara had an intriguing afterlife in works of art produced in the years after Mengs’s death.19 In 1781, it served as a model for an engraving that Azara commissioned from Domenico Cunego (1727–1803), in keeping with Mengs’ own practice of reproducing his works in print. Mengs seems not to have been entirely pleased with the result and commissioned a second engraving by Giacomo Bossi (1750–1804) to illustrate the Italian edition of Winckelmann’s Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (1764), published, with a dedication to Azara, by the Italian archaeologist Carlo Fea in 1783.20 Azara also likely provided the portrait as a model for his head in a twin bust (of Azara and Mengs in a Janus-like configuration), produced by Giovanni Volpato (1735–1803) in 1785.21 (fig. 3)

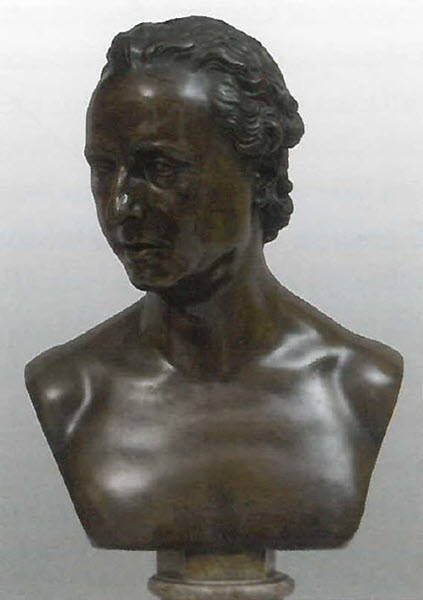

Azara, who outlived Mengs by more than two decades, did his part to promote the posthumous reputation of his friend. In addition to publishing Mengs’s biography and theoretical writings, in which he eulogized Mengs as a new Apelles, Azara arranged for the installation in the Pantheon of a bronze bust of Mengs, later replaced by one in marble, next to the tomb of Raphael. The bust seems to have been one of a pair depicting Mengs and Azara produced by the Irish sculptor Christopher Hewetson (ca. 1737–1798) under the direction of Mengs himself in the years before he died.22 (figs. 4 and 5). The inscription accompanying the bust in the Pantheon contained a dedication to Mengs as a “Philosopher Painter” from “his friend José Nicolás de Azara 1779,” indicating the Spanish diplomat’s great esteem for his colleague and his belief in the importance of his legacy.23

- David Bardeen

-

For Mengs’s career, see Steffi Roettgen, Anton Raphael Mengs, 1728–1779, vol. 2, Life and Work (Munich: Hirmer Verlag GmbH, 2003); Barbara Steindl, “Anton Raphael Mengs,” in The Dictionary of Art, vol. 21, ed. Jane Turner (London: MacMillan Publishers Limited, 1996), pp. 131–34. ↩︎

-

For Meng’s career in Spain, see José Luis Sancho and Javier Jordán de Urríes y de la Colina, “Mengs e la Spagna,”, in Mengs, La scoperta del Neoclassico, exh. cat. (Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen and Schloß, 2001), pp. 71–85. ↩︎

-

For Mengs’s portraits of British aristocrats in Italy, see Steffi Roettgen, Anton Raphael Mengs 1728–1779 and his British Patrons, exh. cat. (London: A. Zwemmer Ltd., 1993). ↩︎

-

Gudrun Maurer, “Mengs and Azara: Testimonios de una Amistad,” in Mengs and Azara: El Retrato de una Amistad, ed. Stephan F. Schröder and Gudrun Maurer (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2013), pp. 10–11. The volume edited by Schröder and Maurer, prepared in connection with an exhibition by the Prado Museum on the original panel painting by Mengs of Azara, provides a history of their friendship and professional collaboration. ↩︎

-

Mengs painted Winckelmann’s portrait ca. 1777, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. See Katharine Baetjer, European Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art by Artists Born Before 1865: A Summary Catalogue (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995), p. 231. ↩︎

-

For Azara’s classical pursuits, see Stephan F. Schröder, “Azara como promotor de les artes y coleccionista de arte clássico,” in Schröder and Maurer, Mengs and Azara, pp. 24–36. ↩︎

-

The herm, now in the collection of the Louvre Museum in Paris, contains an inscription in modern Latin: “this effigy of Alexander the Great, discovered in 1779 (in the Pison villa) at Tivoli, was restored by Joseph Nicolas Azara.” See Denon, l’oeil de Napoléon, exh. cat. (Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Musée du Louvre, 1991), cat. no. 191, pp. 196–97. ↩︎

-

José Nicolás de Azara, The Works of Anton Raphael Mengs, First Painter to His Catholic Majesty Charles III, translated from the Italian, published by the Chev. Don Joseph Nicholas d’Azara, vol. 1 (London: R. Faulder etc., 1796), p. 44. ↩︎

-

Ibid., pp. 7, 9, 55. ↩︎

-

Ibid., p. 39. ↩︎

-

For the Prado picture, see Schröder and Maurer, Mengs and Azara, 2013. For the Getty picture, see Steffi Roettgen, Anton Raphael Mengs: The Portrait of José Nicolás de Azara (London: Trinity Fine Art, 2019). ↩︎

-

Azara, The Works of Anton Raphael Mengs, pp. 27–28. ↩︎

-

Roettgen speculates that Mengs may have copied the Prado portrait when he was next in Rome, between 1777 and 1779. Roettgen, Mengs: The Portrait of Azara, p. 6. ↩︎

-

Ibid., pp. 10–12. ↩︎

-

Azara, The Works of Anton Raphael Mengs, p. 48. Lest the reader conclude that he was reserving such praise only for Mengs’s monumental works, Azara continued that it was “sufficient to see any one of [Mengs’s] paintings to rest convinced of these truths.” [emphasis added] Ibid. ↩︎

-

Steindl, Anton Raphael Mengs, p. 133. ↩︎

-

See Sancho and Jordán, Mengs, La scoperta del Neoclassico, cat. no. 89, p. 269. ↩︎

-

Azara, The Works of Anton Raphael Mengs, p. 28. ↩︎

-

For these later works, see Maurer, Mengs and Azara, pp. 15–19. ↩︎

-

Maurer, “Mengs and Azara,” p. 16. ↩︎

-

For a description of the bust by Volpato, see La scoperta del Neoclassico, pp. 117–28, no. 11. ↩︎

-

Ibid., pp. 116–17, no. 10; see also Maurer, “Mengs and Azara,” pp. 16–19, and Terence Hodgkinson, “Christopher Hewetson, an Irish Sculptor in Rome,” The Volume of the Walpole Society 34 (1952–54), pp. 44–45. ↩︎

-

Maurer, “Mengs and Azara,” p. 17. ↩︎