Between high, forbidding cliffs, where wildflowers bloom in shadow and a stream trickles among the rocks, a ray of light finds its way, touching the birch trunks and wet stone with glints of silver. Young leaves seem to flutter, brilliant green in the sunlight, but in the distance, a dark stand of trees, silhouetted against the pale sky, creates a sense of foreboding. Spring in a Narrow Gorge is a composition of deceptive simplicity, a sharply circumscribed landscape vignette that evokes something more than the rocks and trees it represents. The image is a symbolic rather than a descriptive landscape, an invented scene composed by Arnold Böcklin for maximal atmospheric effect. As a pure landscape, with no mythological or religious staffage, it is virtually unique in the artist’s mature oeuvre.1 The painting nevertheless exemplifies all that is most compelling and mysterious in the artist’s representative style: the suggestive power that made him a hero for the succeeding Symbolist generation and, years later, a source of inspiration for the Surrealists.

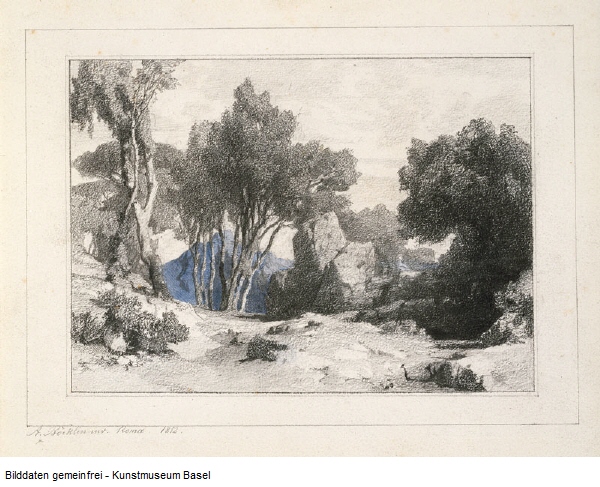

Born in Basel in 1827, Böcklin received his formative training at the Düsseldorfer Kunstakademie, where he studied landscape under Johann Wilhelm Schirmer (1807–1863). The scores of plein-air pencil drawings that survive from this period indicate an early and determined practice of direct nature observation (see fig. 1).2 Although for symbolic landscapes like Spring in a Narrow Gorge he abandoned his earlier methods in favor of a more inventive approach, the eerily convincing materiality of even these imaginary scenes plainly derives from a prolonged study of nature.3 A brief visit to Paris in 1848 brought the young Böcklin into contact with the work of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and the Barbizon painters, whose influence on his own practice, despite his later claims to the contrary,4 can be observed in a number of the artist’s landscapes, including the present picture with its pearly sky, dark trees, thinly painted cliff faces, and tiny flowers picked out with bright flecks of color.

Böcklin’s first visit to Italy in 1850 marked a turning point in his career. In Rome, like so many northern artists before him, Böcklin discovered classical antiquity and Renaissance art. Under the guidance of the art historian Jacob Burckhardt (1818–1897), he spent seven years in the Eternal City, painting his first mythological landscapes in a measured, Poussinist style.5 Despite several extended return visits to Germany, where he taught at the Weimarer Kunstakademie and painted for the Bavarian nobility, and to Switzerland, where he executed an important fresco cycle for Basel’s natural history museum, Böcklin had found his spiritual home in Italy and would return for three extended stays (1862–66, 1874–85, and from 1890 until his death in 1901).

He became a kind of honorary Italian, one of the so-called Deutsch-Römer (German Romans), a triumvirate of German-speaking artists who made their careers during the third quarter of the century painting Italian idylls for a northern clientele.6 Like the other members of the group, Anselm Feuerbach (1829–1880) and Hans von Marées (1837–1887), Böcklin evinced a keen interest in mythological subject matter but tended to depart from classical texts. Deutsch-Römer paintings (sometimes designated Stimmungsmalerei, or mood paintings) tend to evoke moods, rather than specific narratives, and Böcklin’s mature style, which began to emerge during his second Italian sojourn in pictures like Villa by the Sea (1864, oil on canvas, 125 x 175 cm, Munich, Schack-Galerie, inv. no. 11 528), exemplifies this tendency.

Böcklin’s most iconic work, which marked the apogee of his Deutsch-Römer style and won him international fame, was The Island of the Dead (Die Toteninsel, fig. 2).7 He painted six versions of the subject beginning in 1880, inspired by a visit to the island of Ischia, off the coast of Naples. These works epitomize Böcklin’s gift for suggestion and his ability to conjure mood through landscape without clear narrative content. Completed one year before Spring in a Narrow Gorge, The Island of the Dead shares with the Getty picture a symmetrical composition of slender trees framed by towering cliffs. The relationship between the two has been often remarked: both present solemn, portentous landscapes whose silence is punctuated by the imaginary sound of water.8 Some observers have gone so far as to suggest that Spring in a Narrow Gorge offers us a view of the Toteninsel’s interior—a stream of life sprung up on the island of the dead.9 The title Island of the Dead (Die Toteninsel), like those of the Getty picture (Quell in einer Felsschlucht) and most of the artist’s other works sold after 1877, was assigned by his German dealer, Fritz Gurlitt (1854–1893), whose marketing acumen raised Böcklin from semiobscurity and perpetual debt to riches and fame during the 1880s.10 By commissioning a series of engravings after Böcklin’s works in 1882 from the young Symbolist Max Klinger (1857–1920), Gurlitt secured for the painter a mass audience, and, indeed, astonishing international celebrity. Honored with large-scale exhibitions in Berlin, Hamburg, and Basel on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, Böcklin was a veritable cult figure among the Symbolists, who devoted paintings, print series, and journals to him. By the time of his death, he was among the most famous painters in the world. 11

The story of Böcklin’s fall from critical favor forms an interesting chapter in the history of taste. The prominent art critic Julius Meier-Graefe (1867–1935), initially an admirer of Böcklin’s work, published a ravaging assessment of the artist entitled “Der Fall Böcklin” (“The Böcklin Case”) in 1905.12 Modeled on Friedrich Nietzsche’s famous renunciation of Richard Wagner (Der Fall Wagner, 1888), Meier-Graefe’s study classified Böcklin as an aesthetic reactionary, comparing him unfavorably with his French Impressionist contemporaries. Böcklin’s subsequent art historical disgrace was both swift and profound. Scorned by modernist critics, Böcklin received the dubious honor of becoming Adolf Hitler’s favorite painter. The National Socialist arts administration canonized the Swiss Böcklin, alongside the Dutch Rembrandt van Rijn, as one of the great German painters. A copy of The Island of the Dead famously hung in Hitler’s apartments.13

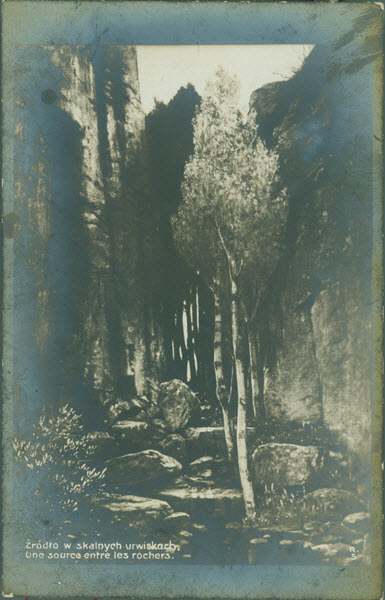

The path of Spring in a Narrow Gorge through the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries reflects the trajectory of Böcklin’s reputation. The picture seems to have been rather famous in the fin de siècle*.* Newspapers noted the stir generated by the “sonderbaren Komposition” (curious composition) on its initial exhibition in Berlin,14 and the painting forms the subject of a poem published as part of a collection of Böcklin-Gesänge (Böcklin odes) in 1898. The poet Felix Lorenz conjured the scene with evident enthusiasm, from “the roots of the trembling trees” that “dip cool, into the stones and ripples” to the “night-dark poplars” of the background, which he compared to the “dreams of heroes.” 15 The great art historian Heinrich Wölfflin included a slide of the picture in his lecture course on German art at the University of Vienna.16 The painting’s reputation, moreover, reached beyond the German-speaking world. Photographic postcards bearing its image were dispatched from Russia and Poland in the 1910s (figs. 3a and 3b).17

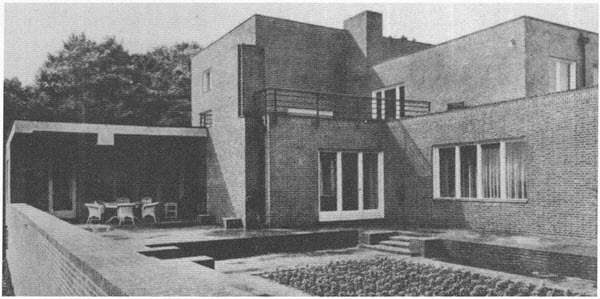

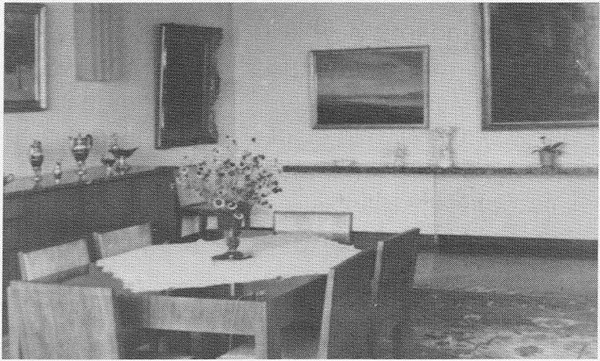

By this time, the picture had found its way into the collection of a family of hat and textile manufacturers in the town of Gübin near the Polish-German border.18 Handed down through three generations, the picture ended up, rather incongruously, in the family’s High Modernist villa, designed by Mies van der Rohe in 1925, where it shared the walls with avant-garde works by Otto Dix, Ernst Barlach, and others (figs. 4a and 4b). After a postwar period spent in an Israeli private collection and characterized, like Böcklin’s postwar reputation, by relative obscurity, the picture reappeared in a series of major exhibitions, beginning in the 1970s, which accompanied a recent revival of interest in the artist.

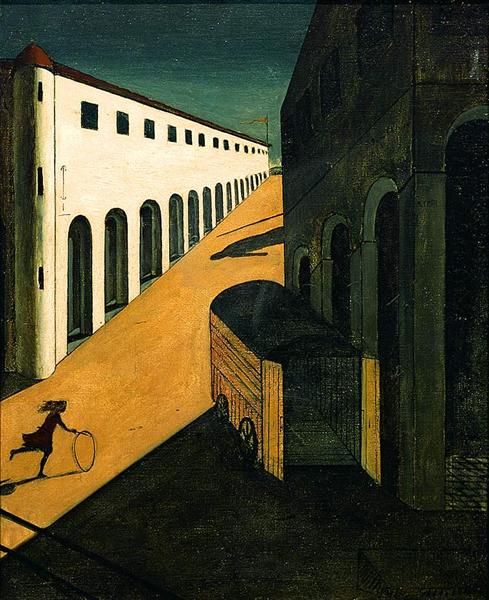

Several of these exhibitions have pointed out Böcklin’s influence on twentieth-century artists, including Max Ernst and Giorgio de Chirico, who had known Böcklin’s work since childhood thanks to its ubiquitous reproductions, and who regarded him as a forerunner to their own explorations of the unconscious.19 De Chirico’s famous Melancholy and Mystery of a Street (fig. 5) shares with Spring in a Narrow Gorge certain unmistakable compositional features—high walls that guide the eye back through rapidly receding space, slanting shadows cast across a bright distance—and, indeed, Böcklin was De Chirico’s favorite artist. He described Böcklin’s work in 1920:

All of his pictures give us the sense of encountering a stranger whom we nevertheless feel we have seen before without being able to remember when or where. It is the same feeling one sometimes has on one’s first visit to a city, when a square, a street, or a house gives one the impression of having been there before.20

Critical admirers and detractors alike have sought in vain to account for the enduring ability of Böcklin’s best pictures to stir something in their viewer’s unconscious. It is this sense of dreamlike familiarity, of uncanny déjà vu, that makes Spring in a Narrow Gorge one of Böcklin’s most extraordinary pictures. It gives us precisely the sensation of finding ourselves in a strange place where we nevertheless feel we have been before.

- Emily A. Beeny

-

Of the more than 150 pictures Böcklin painted between 1875 and 1880, fewer than 40 contain no religious or mythological staffage; most of these are portraits. See Rolf Andree’s catalogue raisonné, Arnold Böcklin: Die Gemälde (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 1977). ↩︎

-

On Böcklin’s drawings, see Hans Holenweg and Franz Zelger’s catalogue raisonné, Arnold Böcklin: Die Zeichnungen (Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 1998). See also Franz Zelger, “Arnold Böcklin als Zeichner,” in Arnold Böcklin, exh. cat., eds. Bernd Wolfgang Lindemann, et al., (Basel: Kunstmuseum, 2001), pp. 66–73; and Dieter Koepplin, “Zu Böcklins Zeichnungen und Kritzeleien,” in Arnold Böcklin 1827–1901, exh. cat. (Basel: Kunstmuseum, 1977), pp. 85–96. ↩︎

-

On the tension between observation and invention in Böcklin’s landscapes, see Marisa Volpi, “Imagination und Wirklichkeit in den Landschaften der Deutsch-Römer,” in "In uns selbst liegt Italien": Die Kunst der Deutsch-Römer, exh. cat., eds. Christoph Heilmann et al. (Munich: Haus der Kunst, 1987), pp. 120–32. ↩︎

-

On Böcklin’s exposure to contemporary French painting and his subsequent reception in France, see Thomas W. Gaehtgens, “Böcklin und Frankreich,” in Schmidt et al 2001 (note 1), pp. 88–111 (esp. pp. 90–92). ↩︎

-

On Böcklin’s friendship with Burckhardt, see Elizabeth Barnes Putz, “Classical Antiquity in the Painting of Arnold Böcklin.” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1979). ↩︎

-

On the Deutsch-Römer, see Heilmann et al. 1987 (note 3) and Marisa Volpi, “Anselm Feuerbach in Rom und im latium: das Italien der Deutsch-Römer,” in Anselm Feuerbach (Speyer 1829–Venedig 1880), exh. cat., eds. Wolfgang Leitmeyer et al. (Speyer: Historischen Museum der Pfalz, 2002). On Böcklin’s relation to the German-speaking expatriate community in Italy, see Cristina Nuzzi et al., Arnold Böcklin e la cultura artistic in Toscana, exh. cat. (Fiesole: Palazzina Mangani, 1980). ↩︎

-

On the Toteninsel and its fame, see: Hans Holenweg, “L’île des morts: Histoire,” in Hommage à l’Île des morts d’Arnold Böcklin, exh. cat. (Meaux: Musée Bossuet, 2001), pp. 11–21; Roger Dadoun, L’île des Morts, de Böcklin: Psychanalysis (Paris: Séguier, 2001); Franz Zelger, Arnold Böcklin, Die Toteninsel: Selbstheroisierung und Abgesang der abendländischen Kultur (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1991); Heinz Zander, Vor Arnold Böcklins Toteninsel (Leipzig: Museum der bildenden Künste, 1986); Norbert Schneider, “Böcklins Toteninsel: Zur ikonologischen und sozialpsychologischen Deutung eines Motivs,” in Arnold Böcklin 1827–1901 1977 (note 2), pp. 106–25. ↩︎

-

On imaginary sound and multisensory experience in Böcklin’s work, see Andrea Gottdang, “‘Man muss sie singen hören’: Bemerkungen zur ‘Musikalität’ und ‘Horarbeit’ von Böcklins Bildern,” in Schmidt et al 2001 (note 1), pp. 130–37. ↩︎

-

See Andree 1977 (note 1), p. 435, no. 362. Böcklin also painted an Island of Life (1888, oil on panel, 94 x 140 cm, Basel, Kunstmuseum, G 1960.12). ↩︎

-

Böcklin believed titles “stifled the imagination.” See Putz 1979 (note 5), p. 130. ↩︎

-

On Böcklin’s relationship with Gurlitt, see also Angelika Wesenberg, “Böcklin und die Reichshauptstadt,” in Schmidt et al. 2001 (note 1), pp. 74–87 (esp. p. 77). On Klinger’s prints and their significance for the Symbolist generation, see Emanuele Bardazzi, An Arnold Bœcklin, exh. cat. (Florence: Saletta Gonnelli, 2001). ↩︎

-

Julius Meier-Graefe, “Der Fall Böcklin,” Die Zukunft 13, vol. 52, no. 43 (1905), pp. 137–48. On the evolution of Meier-Graefe’s opinion of Böcklin and the fallout of this essay, see Christian Lenz, “Erinnerung an Julius Meier-Graefe: ‘Der Fall Böcklin und die Lehre von den Einheiten’ 1905,” in Schmidt et al. 2001 (note 1), pp. 118–29. See also Hans Henrik Brummer, “The Böcklin Case Revisited,” trans. John W. Gabriel, in Kingdom of the Soul: German Symbolism, 1870–1920, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2000) pp. 29–52 (esp. pp. 37–41); Juliane Greten, “Böcklinkritik.” (PhD diss., Universität Heidelberg, 1989); Dieter Honisch, “Der ‘Fall Böcklin’” in A. Böcklin, 1827–1901 1977 (note 2), pp. 14–23. ↩︎

-

Hitler owned eleven works by Böcklin. See Zelger 1991 (note 7), pp. 9–10. ↩︎

-

Basler Nachrichten, no. 66 (March 19, 1885), p. 2: “Die Kunstkritiker und das kunstverständige Publikum in Berlin streiten sich wie gewohnt über den ästhetischen Werth der genialen, aber sonderbaren Komposition.” ↩︎

-

Felix Lorenz, “Quell in der Felsschlucht,” in Böcklin-Gesänge (Berlin: Hermann Feyl, 1898), p. 8. My thanks to Samuel Spinner for his help with these translations. ↩︎

-

Lecture delivered July 8, 1911, and published in Heinrich Wölfflin Kunstgeschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts: Akademische Vorlesungen, ed. Norbert Schmitz (Alfter: Verlag und Datenbank für Geisteswissenshaften, 1993), p. 98 (as “Felsenklamm”). For further elucidation of Wölfflin’s views on Böcklin and contemporary painting, see Thomas W. Gaehtgens, “Les rapports de l’histoire de 1’art et de l’art contemporain en Allemagne à l’époque de Wölfflin et de Meier-Graefe,” Revue de l’art 88 (1990), p. 31. ↩︎

-

These postcards are in the curatorial files of the Paintings Department, The J. Paul Getty Museum. On the adaptation of Böcklin’s work into postcards—including the treatment of Spring in a Narrow Gorge, which was also published in 1927 as a postcard in a copy by Hugo Grimm under the title A Sacred Grove—see Franz Zelger, “Invention, Realisation, Degeneration: Böcklin-Motive und ihre Umsetzung auf Postkarten,” in Heilmann et al. 1987 (note 3), pp. 45–59 (esp. p. 52). ↩︎

-

On the Wolfs, their collection and home, see Leo Schmidt et al., The Wolf House Project: Traces, Spuren, Slady (Cottbus: Lehrstuhl Denkmalpflege, 2001), esp. pp. 42–49. ↩︎

-

The salient example is the exhibition Arnold Böcklin, Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst: Eine Reise ins Ungewiss, which appeared at the Kunsthaus, Zurich (October 3, 1997–January 18, 1998), the Haus der Kunst, Munich (February 5–May 3, 1998), and the Nationalgalerie, Berlin (May 20–August 10, 1998). See the catalogue of the same title, Guido Magnaguagno and Juri Steiner, eds. (Zurich: Kunsthaus Zurich, 1997). See also the exhibition catalogue Hommage à l’Île des morts d’Arnold Böcklin (note 7). On Alberto Giacometti’s affinity for Böcklin, see Reinhold Hohl, “Odysseus und Kalypso: Der Mythus der existentiellen Impotenz bei Arnold Böcklin und Alberto Giacometti” in Arnold Böcklin 1827–1901 1977 (note 2), pp. 115–18. ↩︎

-

Giorgio de Chirico, “Arnoldo Boecklin,” Il Convegno, rivista di letteratura e di arti 4 (1920), pp. 47–53. German translation by Floriana Bernasconi, in Andree 1977 (note 1), pp. 46–50 (esp. p. 48). On De Chirico’s relationship to the work of Böcklin, see “Giorgio de Chirico und der lange Schatten von Arnold Böcklin,” in Magnaguagno and Steiner 1997 (note 19), pp. 204–24. ↩︎