These paintings belong to a suite of decorations commissioned from François Boucher by Jean-François Bergeret (later Bergeret de Frouville, 1719–1783) for his private hôtel in the Marais. In addition to the Getty’s Venus on the Waves and Aurora and Cephalus, the cycle included four pictures on mythological themes, which are now in the Kimbell Art Museum: Boreas Abducting Oreithyia, Juno Asking Aeolus to Release the Winds, Mercury Confiding the Infant Bacchus to the Nymphs of Nyssa, and Venus at the Forge of Vulcan (figs. 1–4).1 Together the six paintings constituted Boucher’s most ambitious decorative cycle to date.

The Hôtel Bergeret (later known as the Hôtel de Marcilly) was constructed in the rue Vendôme (now the rue Bérenger) around 1720 by the financier Abraham Peirenc de Moras.2 Bergeret purchased the building from Moras’s son in April 1768 and must have commissioned Boucher’s decorations almost immediately. Bergeret was the younger brother of a major Boucher patron Pierre-Jacques-Onésyme Bergeret (1715–1785, later Bergeret de Grancourt). His wife’s family also included several collectors of the artist’s work, notably Marin de la Haye (owner of the Hôtel Lambert), Charles-Marin de la Haye, and Blondel d’Azincourt.3 Removed from the hôtel in 1882, the panels bear traces of their original placement in irregular rococo boiseries. Both of the present canvases were cut down from their original shapes (part of the signature on Aurora and Cephalus was lost in this process), and inserts were added to square off the corners.4 The paintings’ original integration into a larger decorative scheme surely accounts for the somewhat broad manner of execution that has occasionally led them to be mistaken for tapestry cartoons.5

The eighteenth century’s preeminent painter of the female nude, Boucher naturally gravitated to depictions of Venus. His oeuvre includes more representations of this goddess than of any other subject. In the first of the Getty panels, Venus, bearing a torch and rose, sits enthroned on her wave under a soaring, cloud-streaked sky. Two putti hover above: one holding a crown of roses; the other, a golden apple, the prize awarded her by Paris. Cupid, sitting in the trough of a wave, turns his back to the viewer and clutches his quiver. A pair of doves nestle in the sand, apparently untroubled by the gaping porpoise at right. The nude’s rounded forms are rendered with solidity and confidence; loose, fluid handling of paint in the draperies, feathers, and—above all—in the luscious, tumbling waves points to the panel’s decorative function.

The picture’s central motif seems to have been adapted from a smaller, oval composition signed and dated 1766 (fig. 5).6 This work belonged to Jean-François Bergeret’s brother, Pierre-Jacques, who served as récéveur général des finances (administrator general of state finances) and amassed one of the largest contemporary collections of Boucher’s work. His posthumous sale included thirty-three objects by the artist, including his “Venus on the waters, accompanied by several Amours, of which one presents a golden apple.”7 In this earlier composition, Venus’s pose is virtually identical. She sits on a wave, holding a torch in one hand and a spray of roses in the other. At right, a putto presents her with the apple; at left, another putto caresses a dove; a third hovers just above her head; and below two porpoises emerge from the waves. The relative positions of Venus’s hands differ from those in the Getty painting; her hair in the earlier version is decked with roses instead of pearls. The images, however, are substantially the same, suggesting that the younger Bergeret may have admired the oval picture in his brother’s collection and asked Boucher to repeat the composition.

The pendant to the Getty Venus depicts a more unusual subject: Aurora, goddess of the dawn, gazing down from the heavens on her love, the mortal Cephalus. In keeping with Homer’s epithet, Aurora appears literally “rosy fingered” as she prepares to shower Cephalus, slack and flushed with sleep, in petals. A bow and fur-lined quiver indicate that Cephalus is a hunter, as does his faithful dog—less a rustic hound, perhaps, than a Parisian lady’s coddled pet—asleep at his side. The treatment of the mortal and his surroundings reflects the same confidence evident in Venus on the Waves: anatomy is firm and rounded; fur and foliage are fluidly rendered. The upper register of Aurora and Cephalus, however, suggests another hand entirely. Aurora’s feet, when compared with those of both Venus and Cephalus, lack bony structure, and the anatomy of her torso is misunderstood. Two pentimenti, visible to the naked eye, suggest a hesitancy at odds with the assured manner of the lower portion: above Aurora’s left hand, a line appears where the drapery was lowered, and the remains of an eye, floating in the putto’s hair, indicate an alteration in the position of his head.8

The subject of Aurora and Cephalus was fairly rare in the eighteenth century and has proved a source of some confusion to modern scholars.9 The Getty painting, for example, is listed as Venus and Endymion in Alexandre Ananoff and Daniel Wildenstein’s catalogue raisonné.10 This work was not Boucher’s first attempt to tackle the story, however. A painting now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts at Nancy was commissioned from the artist in 1733.11 He exhibited another version of the subject, an overdoor for the prince de Rohan’s bedroom at the Hôtel de Soubise, in the Salon of 1739.12 A third version, dated 1764, served as the cartoon for a Gobelins tapestry (fig. 6).13 Of these works, the closest to the Getty composition is the tapestry cartoon. Similarly vertical in format, it places Aurora in the clouds at upper right and the sleeping Cephalus at lower left. Absent from the cartoon, however, are Aurora’s rose petals, a detail Boucher may have gleaned from Guido Reni’s famous ceiling at the Casino Pallavicini Rospigliosi, which Boucher likely saw in the late 1720s while a pensionnaire at the French Academy in Rome.14 Instead of the rose petals, Boucher’s tapestry cartoon conveys Aurora’s identity through the morning star placed on her brow, an attribute she shares with her counterpart at the Hôtel de Soubise. This latter work and the Nancy painting display a somewhat more traditional iconography—notably featuring a golden chariot drawn by the horses Lampus and Phaethon—although they also suggest a level of romantic attachment on Cephalus’s part inconsistent with Ovid’s story, which is essentially one of rape: “It was the second month after our marriage rites,” laments Cephalus in the seventh book of the Metamorphoses,

I was spreading my nets to catch the antlered deer, when from the top of ever-blooming Hymettus the golden goddess of the dawn, having put the shades to flight, beheld me and carried me away, against my will: may the goddess pardon me for telling the simple truth; but as truly as she shines with the blush of roses on her face, as truly as she holds the portals of the day and night, and drinks the juices of nectar, it was Procris I loved; Procris was in my heart, Procris was ever on my lips.15

Still enamored of his wife, Procris, Cephalus proves a reluctant object of Aurora’s lust.16 In the story’s tragic sequel, Aurora returns Cephalus to Procris, but the mortal couple is beset by mutual jealousies and pursued by the goddess’s wrath. Cephalus ultimately kills Procris by accident with the magical spear she has given him as a gift.

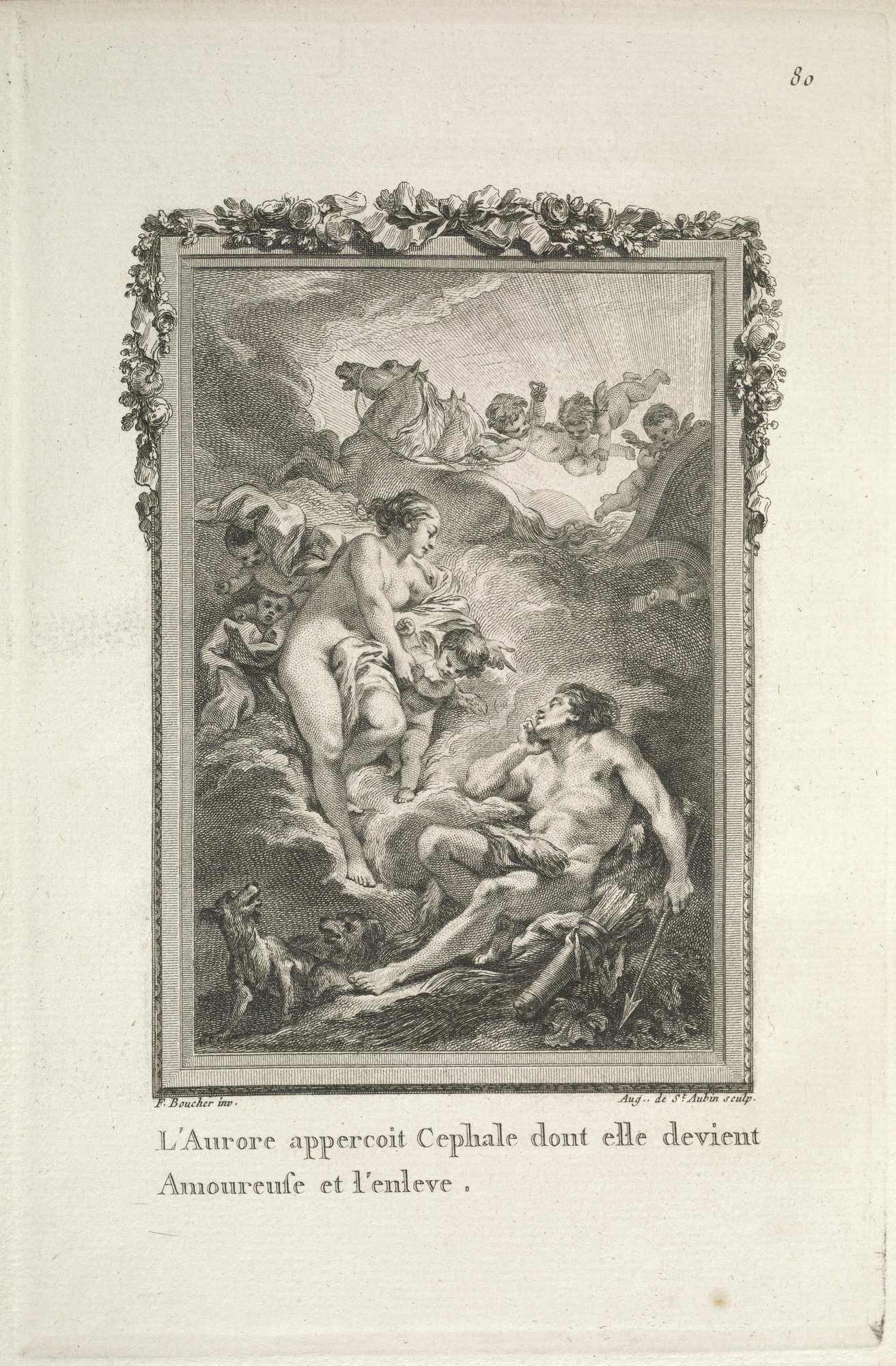

Boucher’s treatments of the subject from the 1730s imply none of the reluctance Ovid ascribes to Cephalus, transforming the faithful husband into a willing recipient of the goddess’s advances. The artist’s return to the subject in the 1760s suggests a greater attentiveness to the text. The passive Cephaluses of the Getty picture and the tapestry cartoon may reflect Boucher’s collaboration on an illustrated edition of the Metamorphoses serially published from 1767 to 1771. 17 This edition, which recycled a translation made by the abbé Bannier in 1732,18 juxtaposed French and Latin texts with engravings by Augustin de Saint-Aubin, Jean Michel Moreau (“Le Jeune”), Noël Le Mire, and Charles Monnet after designs by an array of artists. Boucher supplied designs for a number of stories,19 including that of Aurora and Cephalus. A study associated with the tapestry cartoon served as the model for Saint-Aubin’s engraving of the subject (fig. 7).20 Whether or not Bergeret owned this edition of the Metamorphoses or knew the Gobelins tapestries by the time of the commission, Boucher used the same general design as his point of departure for the Getty painting.

Extracted in 1882 from their boiseries at what was by then known as the Hôtel de Marcilly, the entire Bergeret cycle of decorations entered the collection of Baron Edmond James de Rothschild and passed by inheritance to his son Baron Maurice de Rothschild in 1934. After the German occupation of France in 1940, the paintings were confiscated, along with the better part of the Rothschild collection, by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, or ERR. 21 Still together, the Bergeret paintings likely passed through the ERR’s Paris collection point at the Jeu de Paume, where they were assigned to Hermann Goering’s personal collection, which would comprise over 1,500 works by the war’s end, among them thirty-odd paintings by or attributed to Boucher.22 Restituted in its entirety to the Rothschilds in 1945 or 1946, the cycle may have remained together as late as the early 1970s, when the Kimbell and the Getty acquired their pictures in separate sales.

- Emily A. Beeny

-

Invs. AP 1972.07–10. Alexandre Ananoff and Georges Wildenstein, François Boucher. 2 vols. (Lausanne: La bibliothèque des arts, 1976), vol. 2, nos. 674–77. See also William P. Pillsbury et al., In Pursuit of Quality: The Kimbell Art Museum; An Illustrated History of the Art and Architecture (Fort Worth: The Kimbell Art Museum, 1987), pp. 246–49. ↩︎

-

Paul Jarry*, La Nouvelle-France, ou le Faubourg Poissonnière: Architecture et décorations intérieures* (Paris: Contet, 1930), pp. 9–11. ↩︎

-

Alastair Laing et al., François Boucher 1703–1770, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1986), p. 319, under nos. 84 and 85. ↩︎

-

Condition reports, November 1992 and October 1993 (J. Paul Getty Museum Paintings Conservation Files, 71.PA.54 and 71.PA.55). Those of the inserts that did not overlap with the original paint layer have been left in place by museum conservators during their treatment of the pictures. See treatment report, September 1993 (J. Paul Getty Museum Paintings Conservation Files, 71.PA.54 and 71.PA.55). ↩︎

-

Alastair Laing et al. 1986 (note 3), pp. 318 and 319, under nos. 84 and 85. ↩︎

-

Ananoff and Wildenstein 1976 (note 1), no. 636. ↩︎

-

Bergeret sale, Paris, April 24, 1786, p. 20, no. 52 (sold for fifty-four livres to Gamont): “Venus sur les eaux accompagnée de plusieurs Amours, dont un lui présente une pomme d’or. Cette agréable production est de forme ovale, & porte 16 pouces 6 lignes de haut, sur 14 pouces de large.” ↩︎

-

These pentiments are pointed out in the October 1993 condition report (J. Paul Getty Museum Paintings Conservation File, 71.PA.55). ↩︎

-

Another eighteenth-century French example, which Boucher may have known, is François Lemoyne’s 1724 overdoor for the duc de Bourbon’s bedroom in the Hôtel du Grand Maître at Versailles. See Colin B. Bailey, The Loves of the Gods: Mythological Painting from Watteau to David, exh. cat. (Fort Worth: Kimbell Art Museum, 1992), p. 385. ↩︎

-

See Ananoff and Wildenstein 1976 (note 1), no. 670; and L’opera completa di Boucher (Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1980), no. 708. Ananoff and Wildenstein also miscataloged an Aurora and Cephalus at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nancy, as “Venus and Adonis.” See Ananoff and Wildenstein 1976 (note 1), vol. 1, p. 219, no. 86; that picture’s misidentification apparently dates to the Watelet collection sale of 1786 (June 12, 1786, lot 11), when it was acquired for the French crown. Michel Levey correctly identified the Nancy painting’s subject as Aurora and Cephalus in 1982. See “A Boucher Mythological Painting Interpreted,” The Burlington Magazine 124, no. 952 (July 1982), pp. 438, 442–46. ↩︎

-

Inv. Ananoff no. 86. On the history of this commission, see Laing 1986 (note 3), pp. 136–138, no. 18; and Bailey 1992 (note 9), pp. 380–89, no. 44. ↩︎

-

Ananoff and Wildenstein no. 161. Still in situ at the Archives Nationales. ↩︎

-

Ananoff and Wildenstein no. 481. Musée du Louvre, inv. 2710. ↩︎

-

The ceiling dates to circa 1614. On the seventeenth-century revival of the Aurora and Cephalus story, see Irving Lavin, “Cephalus and Procris: Transformations of an Ovidian Myth,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 17, no. 4 (1954), pp. 260–87. ↩︎

-

Metamorphoses 7.700–709. Trans. Frank Justus Miller (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1977), vol. 3, pp. 391, 393: “Alter agebatur post sacra iugalia mensis, / cum me cornigeris tendentem retia cervis / vertice de summon simper florentis Hymetti / lutea mane videt pulsis Aurora tenebris / invitumque rapit. Liceat mihi vera referre / pace deae: quod sit roseo spectabilis ore, / quod teneat lucis, teeat confinia noctis,/ nectareis quot alatur aquis, ego Procrin amabam; / pectore Procris erat, Procris mihi simper in ore.” ↩︎

-

Venus afflicted Aurora with nymphomania as a punishment for seducing Mars. ↩︎

-

Les métamorphoses d’Ovide, 4 vols. (Paris: Chez Pissot, 1767–71). ↩︎

-

Les métamorphoses d’Ovide, 2 vols. (Amsterdam: R. and J. Wetstein and G. Smith, 1732). Engraved illustrations are by Bernard Picart. His plate for the Aurora and Cephalus story (vol. 1, p. 240) is a wooded scene that bears no resemblance to any of Boucher’s compositions. ↩︎

-

Namely: Mars and Venus surprised by Vulcan; Vertumnus and Pomona; Hercules and Omphale; Pygmalion and Galatea; Venus and Adonis; the rape of Europa; Diana and Acteon; and Bacchus confided to the nymphs of Nyssa. ↩︎

-

Les métamorphoses d’Ovide (note 17), vol. 2 (1768), opposite p. 319. Boucher’s original study in pencil is now in the collection of the châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois Préau, inv. MD0101. ↩︎

-

Nancy H. Yeide, Beyond the Dreams of Avarice: The Hermann Goering Collection (Dallas: Laurel Publishing, 2009), p. 360, nos. A998–A1003. ↩︎

-

Yeide 2009 (note 21), p. 17. Goering’s predilection for bare female flesh (what his own curator, Andreas Hofer, called a “bad taste for florid nudes”) may explain this number. ↩︎