This scene unfolds in the late afternoon shade of an open-air café, or guinguette, beyond the gates of Paris. In the center, three couples dance to the mingled tunes of a fiddle, played in the foreground by a boy in a tricorn hat, and a hurdy-gurdy, cranked by another musician on an improvised stage in the background. A crowd of onlookers—an old man leaning on his stick, a mother and her apple-cheeked child, assorted villagers in their Sunday best—gathers at right to watch the dance. Behind them, a flight of stairs and an archway lead to the parish church. Beside a fountain at the foot of these steps, the stalls of a bustling market offer sweets and trinkets for sale. Young girls peruse a jewelry peddler’s merchandise, and a toddler, grasping his sweet wafer in one chubby fist, stands unsteadily at his mother’s knee. Three shabby figures unpack wares beside the fiddler in the foreground, and a peasant woman, seated at left, embraces her freshly nursed infant, while an urchin sneaks fruit from her upset basket.

The participants in these festivities are not all country folk, however. In the left background, an elegant party takes refreshment at a table laid under the trees. Their gestures and attire bespeak an urbanity that sets these figures apart from the dancers and rustic audience. Gabriel Jacques de Saint-Aubin’s ability to render such distinctions is, of course, the more impressive for the scale at which he painted. This picture, among his largest surviving works, measures just over fifty-two by sixty-five centimeters, yet contains over fifty figures. The scene draws us into what Jules and Edmond de Goncourt called Saint-Aubin’s “Lilliput”—a miniature world of abundant and keenly observed detail.1 With a few deft strokes, the artist captured the satin shimmer of a dancer’s slipper and the seam of her stocking, the pegs and strings of a violin, the glow of a cooking fire, the transparence of a proffered glass, and the flush of exertion in a dancer’s cheek. A dozen beads of paint, each no larger than the head of a pin, evoke the baubles on the trinket seller’s tray; the innocent vanity of the girl who tries on a brooch, admiring herself in a hand-held mirror, is no less wittily conveyed for her Lilliputian scale.

Saint-Aubin painted few pictures, still fewer of which survive. He is best remembered as a draftsman whose “priapic” pen filled the pages of auction catalogues and Salon livrets with tiny, exacting copies of other artists’ work.2 His drawings of street scenes and public entertainments, too, are admired for their spontaneity and finesse and as documents of everyday life in the period, but Saint-Aubin’s original ambitions were rather grander. Coming from a family of artists (his father, Gabriel-Germain, designed embroidery patterns for the crown; his brother Augustin was among the most celebrated engravers of the century), he trained at the Académie Royale as a history painter under François Boucher (1703–1770), Étienne Jeaurat (1699–1789), and Hyacinthe Collin de Vermont (1693–1761). After several unsuccessful bids for the Prix de Rome (he reached the final round three years running but was passed over each time for a better-connected colleague), the artist retreated from his aspirations to grande peinture and accepted a teaching position at Jacques-François Blondel’s architecture school. Occupied through the 1750s with allegorical studies and festival designs, Saint-Aubin found his true subject around 1760 in the daily life of the French capital.

Saint-Aubin’s discovery of contemporary genre subjects coincided with both his brief attempt to reach a broader audience through prints and his period of interest in dance. These two factors were not unrelated, since the proliferation of dancing manuals and the publication of engravings based on contemporary ballets brought dance to the center of popular print culture in mid-eighteenth-century France. Of the seven Parisian street scenes and public entertainments that Saint-Aubin likely painted in the early 1760s,3 at least four were destined for circulation as engravings,4 though none of these seems to have met with commercial success.5 Two of the works—Le carnaval du Parnasse and La guinguette (fig. 1)—commemorated ballets performed at the Opéra and the Théâtre Italien,6 but Saint-Aubin’s engagement with dance went beyond such professional productions. He furnished several illustrations for an instructional manual on contredanses, a new form of social dancing that involved multiple couples.

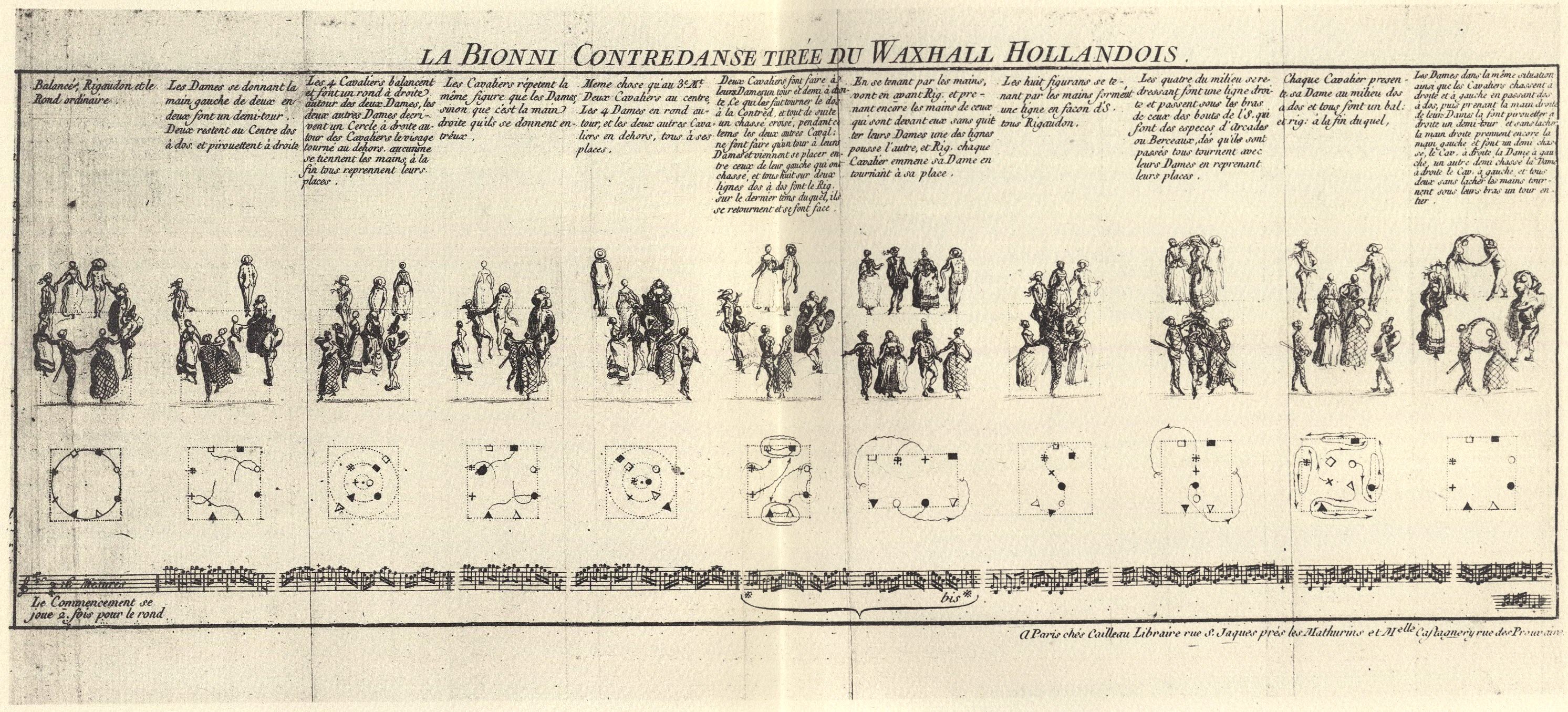

The book in question was Sieur de La Cuisse’s Répertoire des bals, ou Théorie pratique des contredanses, serially published from 1761 to 1763. With diagrams of figures and descriptions of individual steps, the declared purpose of the Répertoire was to bring the contredanse “within everyone’s reach.” Saint-Aubin provided a frontispiece and illustrated two dances, “La Bionni” (fig. 2) and “La Griel.”7 In keeping with La Cuisse’s desire for clarity, Saint-Aubin’s illustrations use familiar costumes from the Italian Comedy to differentiate between the couples: Polinchinelle and Gigogne, Pierrot and Pierrette, Paysan and Paysanne, and so on.8

Although The Country Dance does not seem to depict either of the dances Saint-Aubin illustrated for La Cuisse, its general form adheres to that of a contredanse, with multiple couples and a light, spirited style of movement. The dancers’ costumes in the painting, moreover, also gesture toward the Italian Comedy, albeit with greater subtlety than those in the instructional manual. With his broad, flat hat and trailing sleeves, the rearmost dancer might almost be a Pierrot; his partner all in white, a Pierrette. The foreground dancer in blue and yellow wears a pertly folded skirt and satin corselet whose material is too fine for a country girl and whose form too rustic for a lady: this is plainly a theatrical costume, intended, perhaps, to evoke that of Paysanne. The fluttering ribbons and feathered cap worn by the leftmost dancer, too, savor of the theater, and the uninhibited manner of his movement suggests that he is a professional, unbound by the rules of decorum that governed genteel social dancing.9 The pose of his lower extremities, in fact, echoes that struck by a figure at left in Saint-Aubin’s scene from the ballet La guinguette.10

The painting evokes a hybrid milieu—an intersection of public entertainment and private sociability, of village life and urban leisure, of real people and professional performers—associated with the bals champêtres, suburban venues for music, dancing, and entertainment that achieved wide popularity in mid-eighteenth-century Paris. Advertising in such publications as the Avant-Coureur and charging a modest admission fee, the bals tempered their promise of social mixing with a mild aura of exclusivity. By the 1750s, the most important of them were situated at the entrances to the Bois de Vincennes and the Bois de Boulogne at Saint-Cloud, Auteuil, and Longchamp, but the location of Saint-Aubin’s scene cannot be firmly identified with any of these sites.11 More than a record of a specific bal champêtre, the painting is a fantasy of suburban arcadia, an atmospheric invention and a retort to those who would dismiss Saint-Aubin as a plainspoken reporter of “things seen.”12

The painting’s arcadian reverie owes a debt to Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721).13 The artful vagueness of its locale, its aura of nostalgia, and its merged cast of real-life and theatrical characters recall Watteau’s fêtes galantes of forty years earlier. But also powerfully felt is the sunnier influence of the fête champêtre, associated with Saint-Aubin’s teacher Boucher. A systematic campaign of preparatory drawings (figs. 3–6),14 rather unusual in Saint-Aubin’s oeuvre, confirms the lingering influence of his master on this work.15 Resulting from these drawings, the carefully studied interaction between the principal dancers and the refined gesture of the bowing man in the left background exhibit a grace associated with Boucher’s figures, albeit on a vastly different scale. The ink and wash compositional drawing (fig. 6), Saint-Aubin’s modest substitute for an academic ébauche, demonstrates a skill at assembling disparate studies in a unified composition that he must have acquired through his training as a history painter and his experience in the Prix de Rome competitions.

Saint Aubin seems to have given up oil painting in later life, focusing instead on his tiny, teeming drawings, but an inventory of his possessions made after the artist’s death in 1780 suggests that he retained many trappings of his former work. Alongside some eighty paintings (most of them by other artists) and three hundred drawings appears a collection of battered musical instruments, among them a violin and a hurdy-gurdy, to whose music the figures in his painting are dancing still.16

- Emily A. Beeny

-

Jules and Edmond de Goncourt, “Les Saint-Aubin” (1859) in L’art du XVIIIe siècle, ed. Jean-Louis Cabanès (Tusson: Du Lérot, 2007), vol. 1, pp. 271–322 (esp. p. 282). ↩︎

-

The description of Saint-Aubin’s “priapisme” for drawing was attributed to his colleague Jean-Baptiste Greuze by his brother, Charles-Germain. See Émile Dacier, Gabriel de Saint-Aubin: Peintre, dessinateur et graveur, 1724–1780 (Paris: G. van Oest, 1929), vol. 1, p. 15. ↩︎

-

The precise number of oil paintings Saint-Aubin produced is unknown. See Kim de Beaumont, “Reconsidering Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724–1780): The Background for His Scenes of Paris” (PhD diss., New York University, Institute of Fine Arts, 1998), p. 281. ↩︎

-

La parade au boulevard (London, National Gallery), La promenade de Longchamps (Perpignan, Musée Hyacinthe Rigaud), Le carnaval du Parnasse, and La guinguette (both lost). See Susan Folds McCullagh, “The Development of Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724–1780) as a Draughtsman” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 1981), p. 185. ↩︎

-

The engravings, for example, made by Antoine-Jean Duclos after La parade au boulevard and La promenade were never actually published and exist only in various preliminary states. See Colin B. Bailey et al., Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, 1724–1780, exh. cat. (New York: The Frick Collection, with Somogy Art Publishers, 2007), p. 200, nos. 44 and 45, joint entry by Colin B. Bailey. ↩︎

-

McCullagh 1981 (note 4), p. 183. ↩︎

-

La Cuisse, Repertoire des bals, ou Théorie pratique des contredanses (Paris: Cailleau, 1761–63), ff. 6 and 12. See also Émile Dacier, L’œuvre gravé de Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1914), pp. 9, 100–101 (frontispiece), no. 25; and pp. 102–5, nos. 26 (“La Bionni”) and 27 (“La Griel”). “La Bionni” derived from the successful 1761 ballet Wauxhall hollandois performed at the Théâtre Italien, where Bionni was a choreographer, in 1761. “La Griel” was devised by Perrin, a private dancing master. ↩︎

-

Émile Dacier identified these characters in L’œuvre gravé de Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (note 7), p. 102. On the currency of Italian Comedy in eighteenth-century French popular culture, see François Moreau, Le goût italien dans la France rocaille (Paris: Presses de l’Université Paris-Sorbonne, 2011). ↩︎

-

De Beaumont has made a similar observation about the dancing figures in Saint-Aubin’s pen and ink Fête in a Park at the Cleveland Museum of Art. See Bailey et al. 2007 (note 5), p. 211, no. 49, entry by de Beaumont. ↩︎

-

Louise S. Richards points out the similarity between another figure in this engraving and the female performer in the Cleveland drawing in “Gabriel de Saint-Aubin: Fête in a Park with Costumed Dancers,” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 54, no. 7 (September 1967), pp. 213–18 (esp. p. 215). ↩︎

-

De Beaumont 1998 (note 3), p. 282. ↩︎

-

Even Dacier, Saint-Aubin’s most ardent admirer in the early twentieth century claimed, “Saint-Aubin est incomparable quand il s’agit de représenter une chose vue. En tout autre domaine, son infériorité est manifeste.” See Dacier 1929 (note 2), vol. 1, p. 33. ↩︎

-

De Beaumont discusses the influence of Watteau on Saint-Aubin’s scenes of outdoor entertainment on pp. 304–32 of her 1998 dissertation (note 3). In addition to many more generic similarities between Saint-Aubin’s and Watteau’s work, the background figure in the Getty painting of an old man leaning on his stick is closely related to a figure in Watteau’s L’amour au théâtre italien (Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, ca. 1718). ↩︎

-

Jean Cailleux, who first identified the Getty painting, also associated with it these studies and an additional preparatory drawing, once in the Seligmann collection, in “An Unpublished Painting by Saint-Aubin: ‘Le Bal champêtre,’” The Burlington Magazine 102, no. 686 (May 1960), pp. i-iv (esp. pp. ii-iii). ↩︎

-

The only Saint-Aubin paintings for which a similar wealth of drawings exists, also dating from about 1760, are La parade au boulevard and La promenade de Longchamps. See McCullagh 1981 (note 4) p. 170. ↩︎

-

De Beaumont discusses the contents of the inventory in “Reconsidering Gabriel de Saint-Aubin: The Biographical Context for His Scenes of Paris,” in Bailey et al. 2007 (note 5), p. 45. ↩︎