Valentin de Boulogne, perhaps the greatest of the French caravaggisti, mingled with the stark naturalism fashionable in Rome around 1620 a grave melancholy all his own. He belonged to the international cohort of painters who converged on the Eternal City in the second decade of the seventeenth century and there discovered in the works of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) and his follower Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582–1622) a vivid, psychologically immediate alternative to the erudite intricacies of late Mannerism. Manfredi’s caravaggesque formula—the so-called manfrediana methodus—with its half-length, life-size street characters depicted in shallow, dramatically lit spaces, appealed especially to young artists arriving from war-ravaged Northern Europe, where many had received little formal training in such matters as linear perspective and classical iconography.1 Casting everyday Romans—beggars, prostitutes, soldiers, and street urchins—in biblical stories, the methodus blurred lines between genre and history painting.2 No artist adopted the style with more conviction or pursued it more persistently than Valentin.

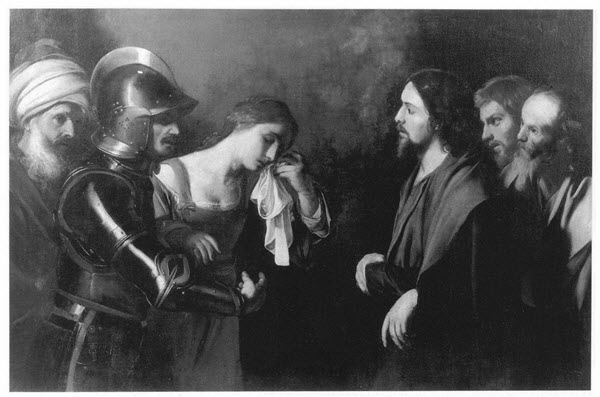

Raked from the left by a harsh white light, Valentin’s figures emerge from their mottled ground as if carved in relief. A young woman with the rounded facial features of a child appears at the center, her wrists bound and eyes downcast. The figure’s disordered appearance—her half-unlaced corset, stray lock of hair, and bare shoulders—suggests the nature of her crime. At right, three Pharisees, marked as such by eyeglasses, a false Hebrew inscription, and a ragged fur cap, crowd in, whiskery and weather-beaten.3 At left, three soldiers present the adulteress for judgment. The glinting metal of their weapons and armor forms a poignant contrast to her tender, exposed flesh. Yet, despite the soldiers’ grip on their prisoner and the accusatory finger one of them points at her, they, too, look down, contemplating words we cannot see, traced in the dust by Christ, kneeling at right. The composition adheres closely to John 8:3–7:

And the scribes and Pharisees brought unto him a woman taken in adultery; and when they had set her in the midst, they say unto him, Master, this woman was taken in adultery, in the very act. Now Moses in the law commanded us, that such should be stoned: but what sayest thou? This they said, tempting him, that they might have to accuse him. But Jesus stooped down, and with his finger wrote on the ground, as though he heard them not. So when they continued asking him, he lifted up himself, and said unto them, He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.

As in the gospel, an unspecified written text hovers outside the scene, just below the center of the frame. Like the soldiers and the Pharisees, the viewer of the painting strains to make out Christ’s invisible writing. What exactly he set down has been the subject of theological debate since at least the fourth century, when Saint Jerome suggested that the inscription was a list of the onlookers’ sins. Subsequent commentators have proposed the complete Decalogue, the commandment against false testimony, or the story of Susannah from the Book of Daniel as alternative texts. But few visual representations of the episode place such explicit, tantalizing emphasis as Valentin’s on the act of inscription and the inscrutability of its result.4

For example, a version of the subject (fig. 1) by Manfredi or–as more recently suggested–by Valentin’s compatriot Nicolas Tournier (ca. 1590–before 1639) takes a more straightforward, sentimental approach: instead of writing on the ground, this upright Christ addresses the weeping woman directly.5 Here is an encounter between miseria and misericordia (misery and mercy, sin and virtue) far removed from the tension and frustrated legibility of Valentin’s picture.6 A closer compositional correlate to the Getty painting is Pietro da Cortona’s (1596–1669) version (fig. 2), wherein Christ gestures downward to an indiscernible inscription, on which a Pharisee trains his eyeglass and the adulteress turns her sorrowful gaze. But while Cortona’s soldier, distracted, looks off to the left, and his Christ turns to reprimand the Pharisees at right, Valentin’s composition exerts a centripetal force that draws all eyes down toward the unseen text. Christ alone lifts his head, gazing fixedly at the accused, who is evidently too consumed by her humiliation to meet his eye.

First published by Roberto Longhi in 1958,7 the Getty picture had no pre-twentieth-century provenance until 2010, when a painting of the same subject and dimensions, attributed to Valentin, was located in the 1714 inventory of the Colonna family’s vast Roman collection under number 374.8 The same work appears, unattributed, in the inventory of 1689 under number 966.9 The authors and current locations of the four other pictures displayed in the camerino at the Palazzo Colonna where this painting hung in 1689 are unknown, and the inventory offers no clues as to their arrangement in the room.10 It is nonetheless tempting to imagine that the Getty picture might have been placed in such a way as to make Christ’s pointing finger indicate not only his invisible inscription but also some element in a neighboring painting. Christina Strunck has described a seventeenth-century installation of this type for Cortona’s version of the subject, which belonged to the Mattei family in the period.11 Strunck has further suggested that a similar network of gesture, narrative, and meaning existed in Baroque hangings in the Palazzo Colonna’s grand gallery,12 but whether such a complex installation would have been attempted in the kind of side room that Valentin’s picture occupied is less certain.

As often displayed in grand galleries as relegated to antechambers, Valentin’s paintings were eagerly collected by Roman noble families of the seventeenth century.13 Even after his countrymen Simon Vouet (1590–1649) and Claude Vignon (1593–1670) had abandoned the style as no longer chic, even after the ascent of Gregory XV to the papal throne and the concomitant turn of official favor to Bolognese classicism, Valentin continued to paint his shadowy pictures—and families such as the Barberini and Colonna to buy them. Only a picturesque death at age forty-one—of a chill caught after plunging into a public fountain at the end of a drunken evening—could put a stop to Valentin’s pursuit of the methodus.14

While Giovanni Baglione’s biography made the lurid story of the painter’s death famous, the details of his early life and the date of his arrival in Rome remain somewhat vague. Born in Coulommiers-en-Brie in 1591, Valentin makes his first definitive appearance in the stati d’anime—the Counter-Reformation Church’s parochial censuses—in 1620, when “Valentino Bologni, francese” is listed under the parish of Santa Maria del Popolo, home to the city’s burgeoning international bohemia.15 He was quickly drawn to a circle of Netherlandish artists in and around the Via Margutta—the so-called Bentveughels (roughly “birds of a feather”), who adopted the freewheeling motto “Bacco, Tabacco e Venere.”16

Valentin’s earliest style (probably of the late 1610s and early 1620s) is characterized by its somber quality, occasionally bordering on hardness, with dramatic shadows, sculpturally defined volumes, and complicated poses. To this manner seems to have succeeded the more ambitious, monumental style of the mid-1620s, in which draperies are rendered in large waves, the use of color is refined, and black is employed somewhat less liberally.17 The Getty painting belongs to a transitional moment between these styles. Valentin’s abundant use of black and the severely lit, sculptural forms point toward such early works as the Expulsion of the Money Changers (fig. 3). The relative simplicity of the composition, serenity of the poses, and subtle sheen of Christ’s robe, however, already belong to a later moment.

Marina Mojana has associated the painting with a pair of works now in Perugia—Christ and the Samaritan Woman and Noli me tangere (figs. 4 and 5)—whose sculptural quality, gestural vocabulary, and treatment of hands (with solid, rounded digits) bear comparison to those in the Getty picture.18 In light of their different formats and, more significantly, the Getty painting’s likely early ownership by the Colonna family, Mojana’s proposal that the three works once formed a triptych remains somewhat speculative. Nevertheless, these pictures, in which Christ confronts repentant or converted women, indicate the artist’s interest in a particular kind of female subject. His known oeuvre, after all, contains only one Virgin.19 Valentin’s pictures are populated, instead, with the prostitutes, fortune-tellers, and fallen women beloved by a young painter whose comrades in the Via Margutta nicknamed him L’innamorato.20

- Emily A. Beeny

-

See Jacques Thuillier, Introduction, in Valentin et les caravagesques français, exh. cat., eds. Arnauld Brejon de Lavergnée and Jean Pierre Cuzin (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1974), pp. xi–xxvi (esp. p. xviii). ↩︎

-

On the manfrediana methodus, see Mina Gregori, “Dal Caravaggio al Manfredi” in Dopo Caravaggio: Bartolomeo Manfredi e la manfrediana methodus, exh. cat. (Cremona: Museo Civico Ala “Ponzone,” 1988), pp. 13–26. ↩︎

-

The Christian emblematic tradition of glasses as a marker of Jews’ blindness to the new dispensation reaches back to the Middle Ages. See Martin Scharfe, “Bildzeugnisse evangelischer Frömmigkeit,” in Volksfrömmigkeit: Bildzeugnisse aus Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, eds. Martin Scharfe, Rudolf Schenda, and Herbert Schwedt, (Stuttgart: Spectrum-Verlag, 1967), pp. 43–75, (esp. p. 49). On the conventions of false Hebrew in early modern European painting, see Shalom Sabar, “Between Calvinists and Jews: Hebrew Script in Rembrandt’s Art,” in Beyond the Yellow Badge: Anti-Judaism and Antisemitism in Medieval and Early Modern Visual Culture, ed. Mitchell B. Merback. (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2008), pp. 371–404 (esp. pp. 374–75). ↩︎

-

On theological conjectures regarding the content of the text, see Gail R. O’Day, “John 7:53–8:11: A Study in Misreading,” Journal of Biblical Literature 111, no. 4 (Winter 1992), pp. 631–40. See also E. Power, “Writing on the Ground (Joh. 8. 6.8),” Biblica 2 (1921), pp. 54–57. ↩︎

-

Traditionally given to Manfredi, this picture was reattributed to Tournier by Nicole Hartje in Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582–1622): Ein Nachfolger Caravaggios und siene europäische Wirkung (Weimar: VDG, 2004), p. 381, no. D.1. ↩︎

-

The Manfredi/Tournier painting elides the first and second parts of the story. In the Gospel, Christ does not speak to the woman until her persecutors have departed (8:9–11). Such elisions are common in painting largely because Saint Augustine’s interpretive emphasis on the second portion of the story led to a widespread understanding of the entire episode as an encounter between miseria and misericordia. See “Homily XXXIII,” in Homilies on the Gospel According to St. John and His First Epistle, 2 vols. (Oxford: John H. Parker, 1848), vol 1, p. 477. ↩︎

-

As in a private Roman collection. See Longhi, “A propos de Valentin,” La Revue des arts 8, no. 2 (March-April 1958), pp. 58–66 (esp. p. 62). ↩︎

-

The inventories have been published by Eduard Safarik. See Collezione dei dipinti Colonna: Inventari 1611–1795, ed. Anna Cera Sones, (Munich: K. G. Saur, with The Provenance Index of the Getty Art History Information Program, 1996), p. 274: “Un quadro in tela dj p.mi otto, e cinque rappresentante l’Adultera avantj al Salvatore originale dj Monsù Valentino con sua cornice negra, e filettj d’oro spett.e come s.a.” ↩︎

-

Safarik 1996 (note 8), p. 193, no. 966. And possibly the inventory of 1679, p. 130, no. 245, though this canvas, of smaller dimensions than the Getty picture and set in a more elaborate frame, may be a different work. ↩︎

-

These were: a Madonna with Saints John and Joseph; an allegory of fortune; a mythological scene with Mercury and two unidentified gods; and a Denial of Saint Peter. ↩︎

-

Cortona’s painting was displayed above a series of small, highly detailed cavalcade pictures, at which his monocled Pharisee consequently seemed to peer and his Christ to draw the viewer’s attention. See Christina Strunck, “Trends and Turning Points in Early Modern Gallery Design in Rome,” (Paper presented at The Display of Art in Roman Palaces 1550–1750, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA, December 2–3, 2010). ↩︎

-

See Strunk, Berninis unbekanntes Meisterwerk: Die Galleria colonna in Rom und di Kunstpatronage des römischen Uradels (Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2007). ↩︎

-

See Brejon de Lavergnée and Cuzin 1974 (note 1), esp. p. 188. ↩︎

-

Giovanni Baglione retailed this story in Le vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti dal pontificato di Gregorio XII: Fino à tutto quello d’Urbano Ottavo, 2nd ed. (Rome: Manelfo Manelfi, 1649), p. 338. ↩︎

-

He may have arrived in Rome as early as 1617 or even 1611, although variations in the orthography of his name in these years invite caution. See Jacques Bousquet, “Valentin et ses compagnons,” Gazette des beaux-arts 17, pér 6, 1317e livraison (October 1978) pp. 101–14 (esp. 106–7). ↩︎

-

On the Bentveughels, see Goffredo J. Hoogewerff, Via Margutta: Centro di vita artistica (Rome: Quaderni di storia dell’arte, 1953). ↩︎

-

On the development of Valentin’s style, see Pierre Cuzin, “Pour Valentin” (1975), in Figures de la réalité: Caravagesques français, Georges de La Tour, les frères Le Nain . . ., eds. Dominique Cordellier et al. (Paris: Hazan and INHA, 2010), pp. 80–97 (esp. pp. 87 and 91). Lacking substantial documentation, the chronological ordering of Valentin’s oeuvre remains somewhat speculative. ↩︎

-

See Mojana, Valentin de Boulogne (Milan: Eikonos Edizioni, 1989), pp. 72–76, nos. 10–12. Christ’s pointing hand in the Getty painting is mostly lost and heavily repainted, but those of the adulteress offer a worthwhile comparison. ↩︎

-

In the Holy Family with Saint John at the Galleria Spada, Rome. ↩︎

-

I.e. “the lover.” Marina Mojana has posed the question, reasonable in light of Valentin’s apparent lack of romantic attachments: “Innamorato di chi o di che cosa?” See Mojana 1989 (note 18), p. 43. On artists’ models in seventeenth-century Rome, see Patrizia Cavazzini, Painting as Business in Early Seventeenth-Century Rome (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008), esp. pp. 70–80. ↩︎