In an homage to the painter published by the Académie des Beaux-Arts the year after he died, Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld was reported to have said that he learned to do études (studies) while making tableaux (paintings) and to do tableaux while making études.1 At the time that this was printed, in 1847, the difference between an étude and a tableau was a point of heated debate among critics and painters in the French art world. Bidauld’s oeuvre, and in particular the cache of sketches made public at his estate sale in 1847, added a new dimension to the discussion. Works like View of Bridge and Part of the Town of Cava, Kingdom of Naples were of an étude-like scale but presented a degree of finish associated with tableaux. Although Bidauld painted tableaux across his career, exhibiting them at the Salon starting in 1791, his art-historical reputation rests on his small-scale, meticulously rendered, plein-air paintings.

Bidauld was trained in Lyon, attending courses at the Académie there alongside his almost identically named brother, Jean-Pierre-Xavier Bidauld (1745–1813). Jean-Joseph moved to Paris in 1783 with a letter of introduction to the leading landscape painter of the day, Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714–1789).2 He spent two years absorbing the classical landscape tradition of Claude Lorrain (1604–1682) and Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) through his teacher Vernet, and making copies of Dutch paintings for a picture dealer named M. Dulac. In 1785, Dulac helped pay for Bidauld’s trip to Rome. He spent five years in Italy, traveling the Roman states, Tuscany, and the Kingdom of Naples. He painted the hill towns of Subiaco, Narni, Civita Castellana, Isola di Sora, and the mountains of the Abruzzi, establishing an informal tour that would be followed by landscape painters for generations, including, most famously, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. On his return to France in 1790, Bidauld submitted classical landscapes, or paysages historiques, to the Salon, where they were accepted in 1791 and regularly thereafter for the duration of his career. He was the first landscape painter to be elected to the Institut de France, in 1823, and to be awarded the Legion d’honneur, in 1825.

Some one-hundred small paintings were exhibited publicly at his estate sale on his death.3 They received a favorable response, much as Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes’s sketches had the previous decade, and several were purchased by King Louis-Philippe. Although qualified as études due to their small scale, their execution on paper support, and the freshness of their conception, they are distinguished by their high degree of finish, and they seem to have functioned less as notations for later production than as completed works in their own right. Despite claims that no painter spent more time working outdoors sitting before a single site than Bidauld, these works were likely started outdoors and finished in the studio.4

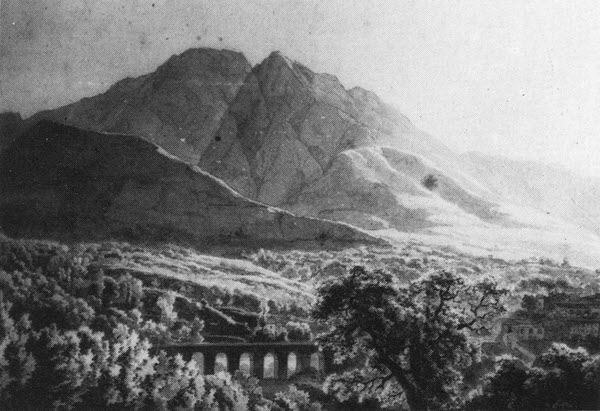

The present work shows the Ponte de San Francesco moving across the foreground toward the town of Cava, against the dramatic ridgeline of the Lattari Mountains. Bidauld meticulously depicts the precisely rhyming arches of the bridge against the uncultivated green growth of the hills, the warm-toned cluster of buildings, and the tendril of smoke escaping into the pristine sky. According to Suzanne Gutwirth’s catalogue raisonné, the Musée Calvet in Avignon has a similar view in both crayon and wash (fig. 1) and oil on canvas (fig. 2), in the latter of which the point of view is lower and turned to the right, with a more complete view of the town.5 Bidauld also painted exactly the same view, challenging himself to construct singular images with extremely subtle variations in hue.6 In 1791, he listed as one of his principal pictures at the Salon, “Vue de la ville et du pont de la Cava au Royaume de Naples, commandé par M. Godefroy et executé a Rome.”7

The intensity of the small paintings like the Getty View of Cava, particularly in relation to the artist’s more static, reserved Salon paintings, suggest the degree to which Bidauld was profoundly inspired by the process of transcribing nature outdoors, sur le motif. There is a kind of hypnotic immersion in the moment, on-site, reminiscent of a work by Théodore Rousseau (fig. 3). It is all the more unfortunate then that Bidauld so opposed the admission of Rousseau’s paintings into the Salon exhibitions during the 1840s, a reactionary stance that sealed Bidauld’s fate in the art-historical record as retardataire.8

- Mary G. Morton

-

Désire-Raoul Rochette, Notice historique : Notes sur la vie et les ouvrages de M. Bidauld, paysagiste, membre de l’Institut (Paris: Académie des Beaux-Arts, 1847), pp. 39–40. ↩︎

-

For biographical information on Bidauld, see J. De Gaulle, Notes sur la vie et les ouvrages de M. Bidauld, paysagiste, membre de l’Institut (Paris: Académie des Beaux-Arts, 1847). See also Suzanne Gutwirth, Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld (1758–1846): Peintures et dessins, exh. cat. (Carpentras: Musée Duplessis, 1978.) ↩︎

-

Schroth, Paris, March 25–26, 1847, Vente d’études peintes par feu Bidauld. Reprinted in Philip Conisbee, French Paintings of the Fifteenth through the Eighteenth Century (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2010), p. 10. ↩︎

-

Raoul-Rochette 1847 (note 1), pp. 39–40. ↩︎

-

Gutwirth 1978 (note 2), cat. no. 51 (27.5 x 53.5 cm) and Gutwirth 1978 (note 2), cat. no. 50 (30 x 47 cm), inscribed on the back “Rme de Naples 1811.” ↩︎

-

See View of the Bridge and the Town of Cava, Kingdom of Naples, oil on paper laid down on canvas, 21.6 x 28.6 cm (8 1/2 x 11 1/4 in.), Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, PD.32-2006. ↩︎

-

“View of the Town and Bridge of Cava in the Kingdom of Naples, Commissioned by Mr. Godefroy and Executed in Rome.” De Gaulle 1847 (note 2), p. 5. ↩︎

-

Théophile Gautier singled out Bidauld and Jean-Victor Bertin as the hopelessly conservative, principal enemies of Rousseau. See Peter Gallassi, Corot in Italy: Open-Air Painting and the Classical-Landscape Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991) nn. 17, 234. ↩︎