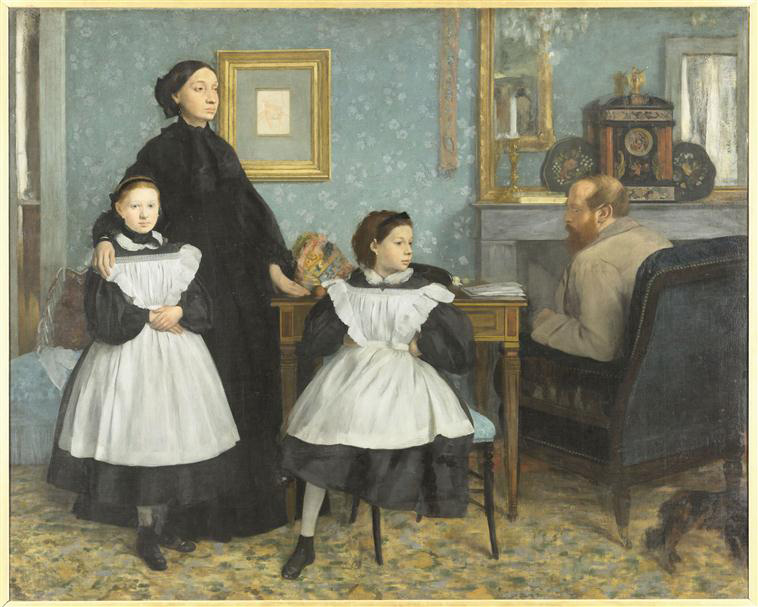

James Tissot completed this portrait during his first career in Paris, which began in the late 1850s and ended on his departure for London in 1871 following the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune. His career in England, where he became a successful painter of British young ladies in fashionable dress, as well as the biblical illustrations of his second Parisian career of 1882–1902, dominate the Tissot literature, overshadowing his complex art-historical role during the artistically vibrant last decade of the Second Empire in Paris.1 During the 1860s, when Modernist painting is generally recognized to have originated, Tissot straddled the academic and avant-garde contemporary art worlds, and he was absent from Paris between 1871 and 1882, the seminal years in the development of Impressionism. Nevertheless, the Getty Museum’s Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon and the Musée d’Orsay’s Portrait of the Marquis and Marquise de Miramon and Their Children (fig. 1), alongside a letter written by Tissot in the collection of the Getty Research Institute (fig. 2), illuminate his active role among the young, progressive painters living in Paris in the 1860s.

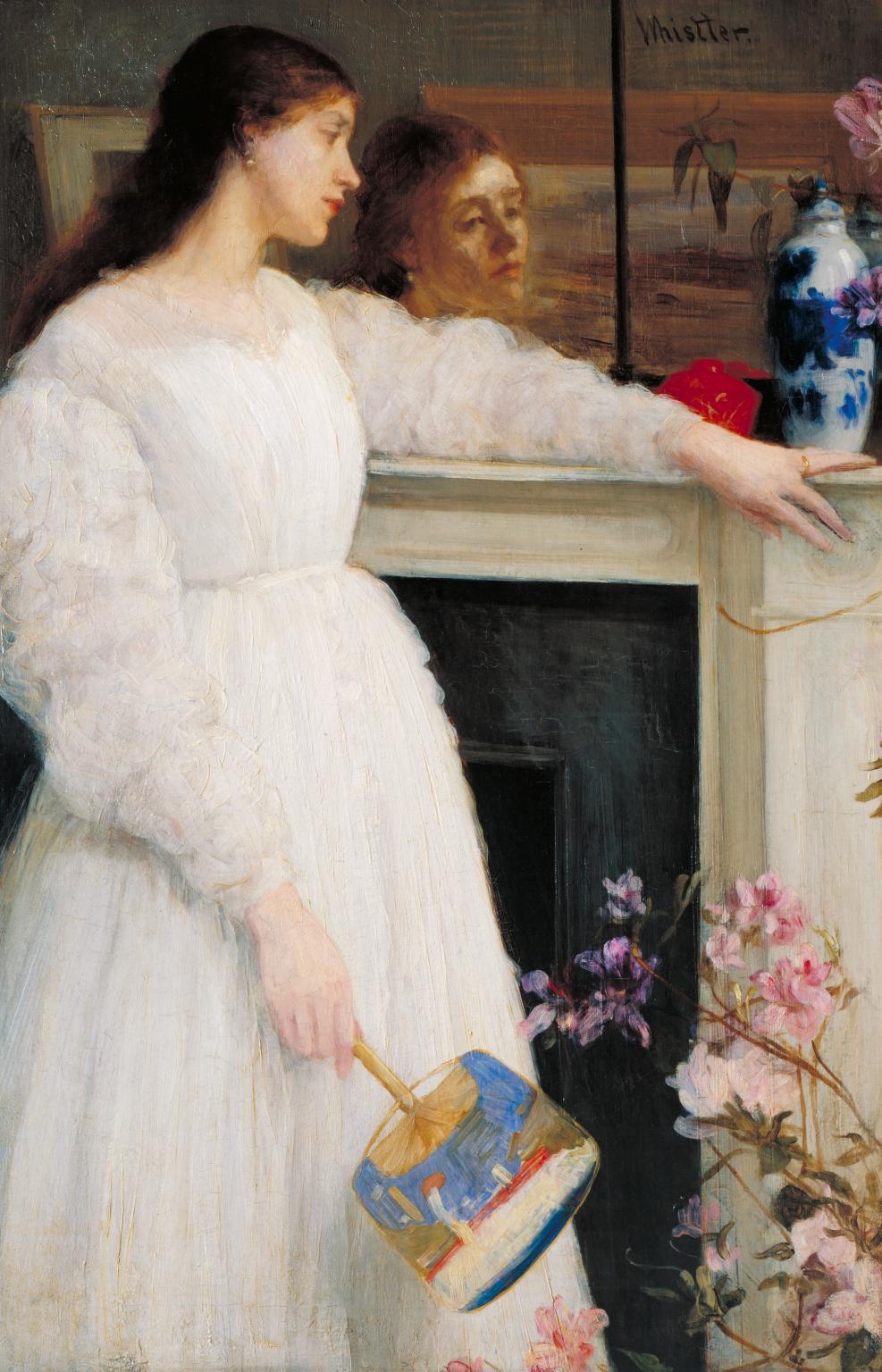

After training with the academic painters Louis Lamothe (1822–1869) and Hippolyte Flandrin (1809–1864) in the 1850s, Tissot became a regular participant in the annual Paris Salon, where he cast an attentive eye on the most innovative painters in both Paris and London. Alongside his close colleagues Edgar Degas (1834–1917), James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), Alfred Stevens (1823–1906), and Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904), he responded to the influence of Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) and Édouard Manet (1832–1883), the leaders of the artistic avant-garde, as well as to Charles Baudelaire’s call for “painting of modern life.” He moved away from the medieval genre scenes of the early 1860s to produce a series of contemporary genre and portrait paintings considered by critics to be striking in their originality, such as Portrait of Mlle. L.L. (1864, Musée d’Orsay), The Two Sisters (1863, Musée d’Orsay), Japanese Girl Bathing (1864, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon), and Le cercle de la rue Royale (1868, Musée d’Orsay).

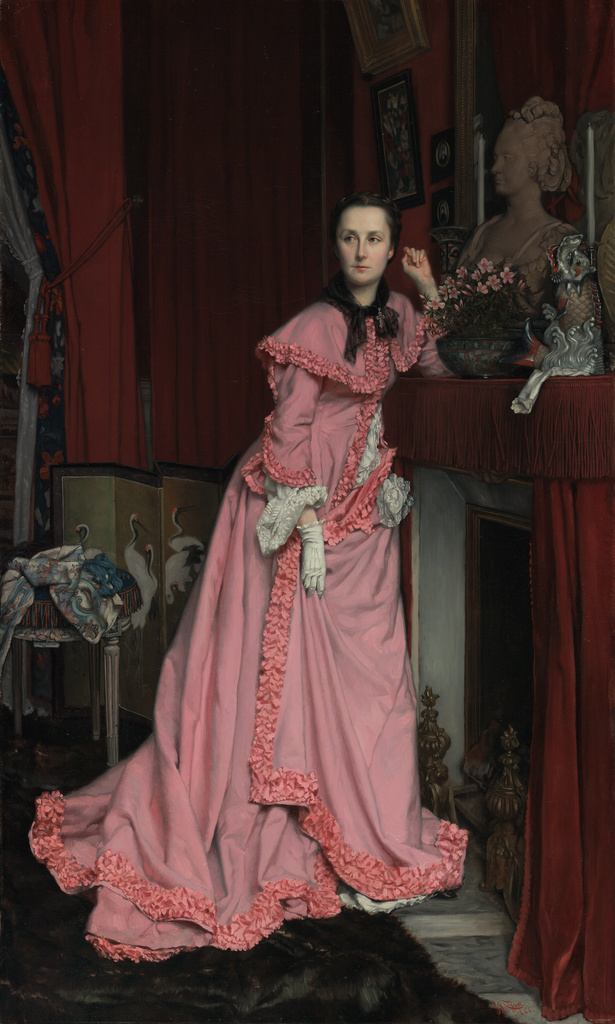

Painted in 1866, Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon quietly asserts its modernity while fulfilling its function within the fabric of French high society. The painting represents an elegant thirty-year-old woman as an icon of Second Empire fashion and social ascendance, but with an air of fragility. The sitter, Thérèse-Stephanie-Sophie Feuillant (1836–1912), stands in one of the rooms of the château de Paulhac in the Auvergne, her husband’s family seat. On the wall hang a Netherlandish painting, some miniature portraits, and a gilt-framed mirror. Behind the marquise is a Japanese screen showing cranes on a gold ground, which together with the East Asian ceramics on the mantelpiece suggest Feuillant’s participation in the vogue for all things Japanese (and often Chinese)—known as japonisme—that developed during the 1860s in France. Next to the screen stands a Louis XVI stool on which lies a heap of needlework, a sign of upper-class domesticity. On the mantelpiece alongside the vases sit an eighteenth-century terracotta bust (possibly a portrait of a member of her husband’s family by the late-eighteenth-century sculptor Philippe-Laurent Roland), a bouquet of delicate pink and rose flowers (perhaps the Asian azalea), and a discarded white glove. The marquise wears the other glove on her right hand, gently holding a fold of her voluminous dressing gown, which falls gracefully around her onto the fur-covered marble floor. Her exposed left hand reveals a narrow wrist and delicately tapered fingers, the pale, pink-tinged complexion of which matches that of her fine, unlined face. An aquiline nose dominates her features, which include round eyes and a small mouth. Her hair is neatly braided on top of her head, and she wears a black-lace scarf and a silver cross around her neck, additional signs of her refined, respectable social position.

As if caught in a pensive moment, the marquise looks off to her right, avoiding direct visual contact with the painter, as well as the viewer. A gesture that reaffirms her elevated social position, it also diverts attention to her spectacular costume, a velvet, rose-colored peignoir, caped à la pèlerine (pilgrim-style), and edged with deep pink ruffles. Two years later, Claude Monet (1840–1926) would employ a similar strategy in his spectacular Madame Gaudibert (1868, Musée d’Orsay), in which the sitter, wearing a sumptuous copper-colored dress, turns away to offer only her profile while removing with her naked left hand the crème-colored glove of her right. Both painters answered Baudelaire’s prescription to artists to participate in modernity by portraying contemporary fashion. In Baudelaire’s criticism, as in these paintings, identity is expressed most forcefully through fashion.2

Not herself noble-born, Feuillant was descended from a grand bourgeois family with interests in the mines of northern France. Her father, Xavier Feuillant, a wealthy industrialist and an officer and supporter of the Bourbon Restoration, was a “Gentilhomme ordinaire,” an honor bestowed by King Charles X. Thérèse inherited a significant fortune, which she brought to her marriage in 1860 to René de Cassagnes de Beaufort, Fifth Marquis de Miramon (1835–1882). The marquis was the head of a noble family whose ancestry traced back to the eleventh century and whose title was conferred in 1768 by Louis XV. René de Miramon was an active member of Parisian high society, a racing amateur, and like his wife, an Anglophile. He was elected to the Jockey Club, the most exclusive social club in Paris, in 1858, with one of his sponsors being the vicomte Daru, a founder of the seaside resort of Deauville. The marquis was Tissot’s primary patron at the time of this portrait, and went on to commission several more paintings from him, including the family portrait acquired in 2006 by the Musée d’Orsay (fig. 1), and the similarly large-scaled group portrait of another of the marquis’s clubs, Le cercle de la rue Royale.

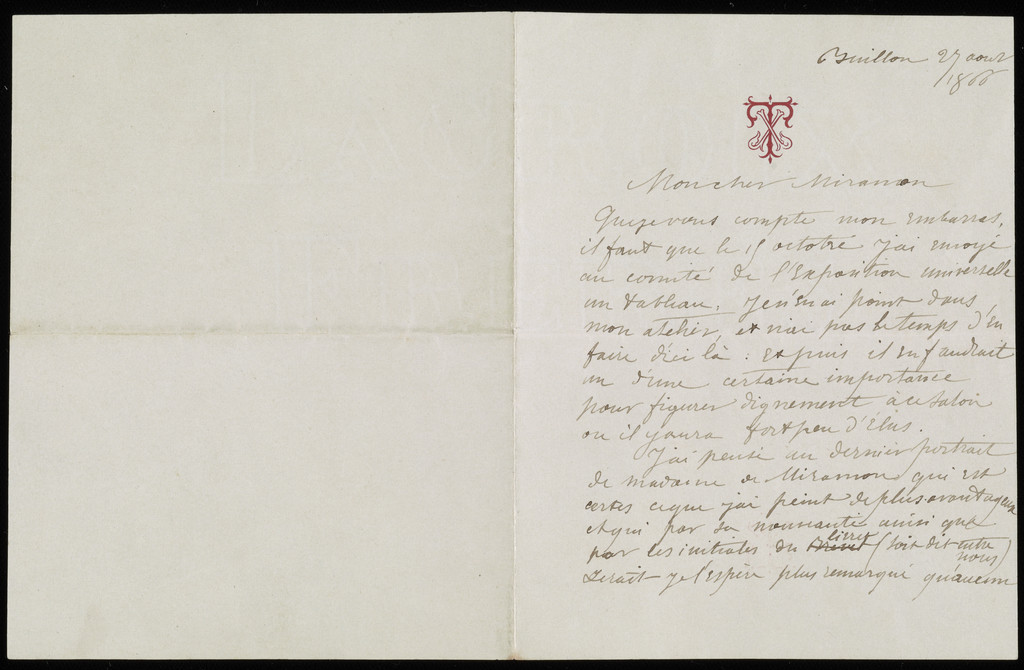

Tissot must have been singularly pleased with the Getty canvas, for he asked his patron if he could borrow the painting back to exhibit at the 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle. This spectacular event, attracting millions of tourists to Paris to witness displays on the latest in French engineering, technology, architecture, and art, provided a powerful opportunity for artists to promote themselves (both Courbet and Manet constructed their own private pavilions near the fair grounds). The Getty Research Institute owns the letter in which Tissot makes his request to the marquis (fig. 2, translated below). The marquis conceded, and Tissot exhibited both the portrait and a romantic genre scene, Le rendez-vous.

The letter is of interest both in the way Tissot characterizes the Getty painting and in the familiar tone he takes with this prominent member of Second Empire high society:

Buillon, August 27, 1866

My dear Miramon,

I must share with you my awkward situation, I need to have sent a painting by October 15 to the Committee of the Exposition Universelle. I will not be in my studio, and I don’t have time to do another one by then from here: and plus it should be an important one to do me justice in this salon in which very few [artists] will be elected.

I thought of the recent portrait of Madame de Miramon which is certainly one of the most advantageous [avantageux] I have ever painted, and which for its novelty as much as well as for the letters in the booklet (as they say, between us) [par les initiales du livret (soit dit entre nous)] would be, I hope, among the most remarked upon paintings. It is true that it will attract perhaps too much attention for its originality, but, in sum, it’s better like that, and if you would like to brave the publicity, I would be delighted, and indebted to you for the advantages which the exhibition will bring me.

Where does this note find you? Is it at Galliac, or at Dieppe? Here in any case is my address:

JT at Chateau de Buillon

près Guingey (Doubs)

and if you consent, dear friend, I would be indebted to you for this new proof of friendship.

Yours,

James Tissot

My respects to Madame de Miramon and if that mad Xavier is with you my good wishes to him too.3

By 1866, Tissot, born in Nantes of a successful textile manufacturer, had achieved a significant level of not only financial but also social success in the French capital. He had built for himself an imposing house on avenue de l’Impératrice, a broad new street linking the place de l’Etoile and the bois de Boulogne, and filled it with fashionable decorations.4 Tissot avidly collected art objects from China and Japan and pictured them in many of his paintings of women in interiors. Like de Miramon, he was both a japoniste and an Anglophile, and he frequented some of the same exclusive clubs as the marquis.

Of equal interest as the informal, friendly tone of the letter are the references to originality and novelty in Tissot’s description of the picture. The painter suggests that he is testing the fine line between fashion and propriety in this painting, an enterprise seemingly condoned by his patron. Within a traditional format and genre, Tissot signaled his participation in the avant-garde in his focus on the relatively informal but highly fashionable dress, on the marquise’s interest in japonisme, and in the painting’s reference to contemporary works by Manet, Whistler, and Degas.

Manet painted Woman with a Parrot the same year Tissot painted the marquise, and it is probable that the artists knew of one another’s compositions given their friendship and the sociability of each of their studios (fig. 3). Manet portrays his favorite model, Victorine Meurent, wearing a peignoir similar in its pinkish hue to that worn by the marquise, but looser and simpler, next to an oddly placed exotic parrot on a perch, all in a Velazquez-inspired empty dark interior. Having been twice featured sensationally naked (in Luncheon on the Grass, Salon des Refusés, 1863, and Olympia, Salon of 1865), here Meurent is just clothed in what was known as a robe d’intérieur or a negligée*.* In the 1870s in England, the looseness of the garment and the ease of disrobing relative to street attire associated such dress with loose morals.5 The comparative formality of the marquise’s peignoir safely distances her from such associations, but the frisson of Manet’s composition, shown in Manet’s private pavilion during the Exposition Universelle of 1867, would surely have affected attentive viewers of Tissot’s portrait hanging in the pavilion across the Champs Elysées.

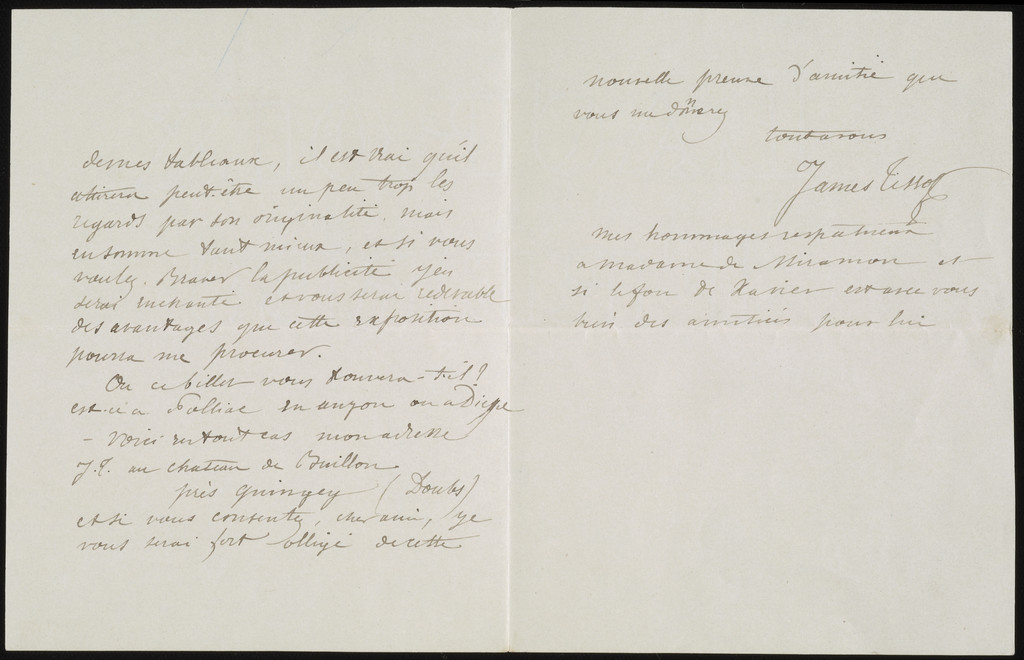

Another artistic confrere who impacted Tissot’s painting in the later 1860s was Whistler, whom Tissot befriended as early as 1856, when according to Théodore Duret, they painted together in the Louvre, copying Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Roger délivrant Angélique.6 Indeed, Whistler may have been partly to blame for Tissot’s decision to anglicize his first name to James in 1859. Whistler’s Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, a mysterious portrait of an auburn-haired girl in a sumptuously rendered white dress, had caused a stir at the Salon des Refusés in 1863.7 In 1867, Whistler sent another of his “symphony” paintings, Symphony in White, No. 3, from his London studio to Paris for his friend Fantin-Latour to see. This painting of two women dressed in white, alongside a white divan, greatly impressed Fantin-Latour, who wrote back that he and Alfred Stevens liked it very much and that Tissot “was like a madman in front of it, jumping for joy.”8

Whistler and Tissot shared an aggressive japonisme in addition to their Anglophilia, competing as collectors for the goods in Madame de Soye’s shop, La Porte Chinoise, on rue de Rivoli in the mid-1860s.9 Tissot’s emphasis on the marquise de Miramon’s dress and her Japanese bibelots was in line with Whistler’s aestheticist views on the harmony of fashion, art, and design, and specifically with Whistler’s foregrounding of the decorative as the most expressive element in portraiture.10 The de Miramon portrait corresponds to Whistler’s series of paintings of beautifully attired ladies in interiors surrounded by japonaiseries, such as Purple and Rose: The Lange Leizen of the Six Marks (1864, Philadelphia Museum of Art) and in particular Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl (fig. 4) in which the young woman looks thoughtfully away from the viewer, standing at the mirrored mantelpiece next to a Japanese ceramic and azalea branches.

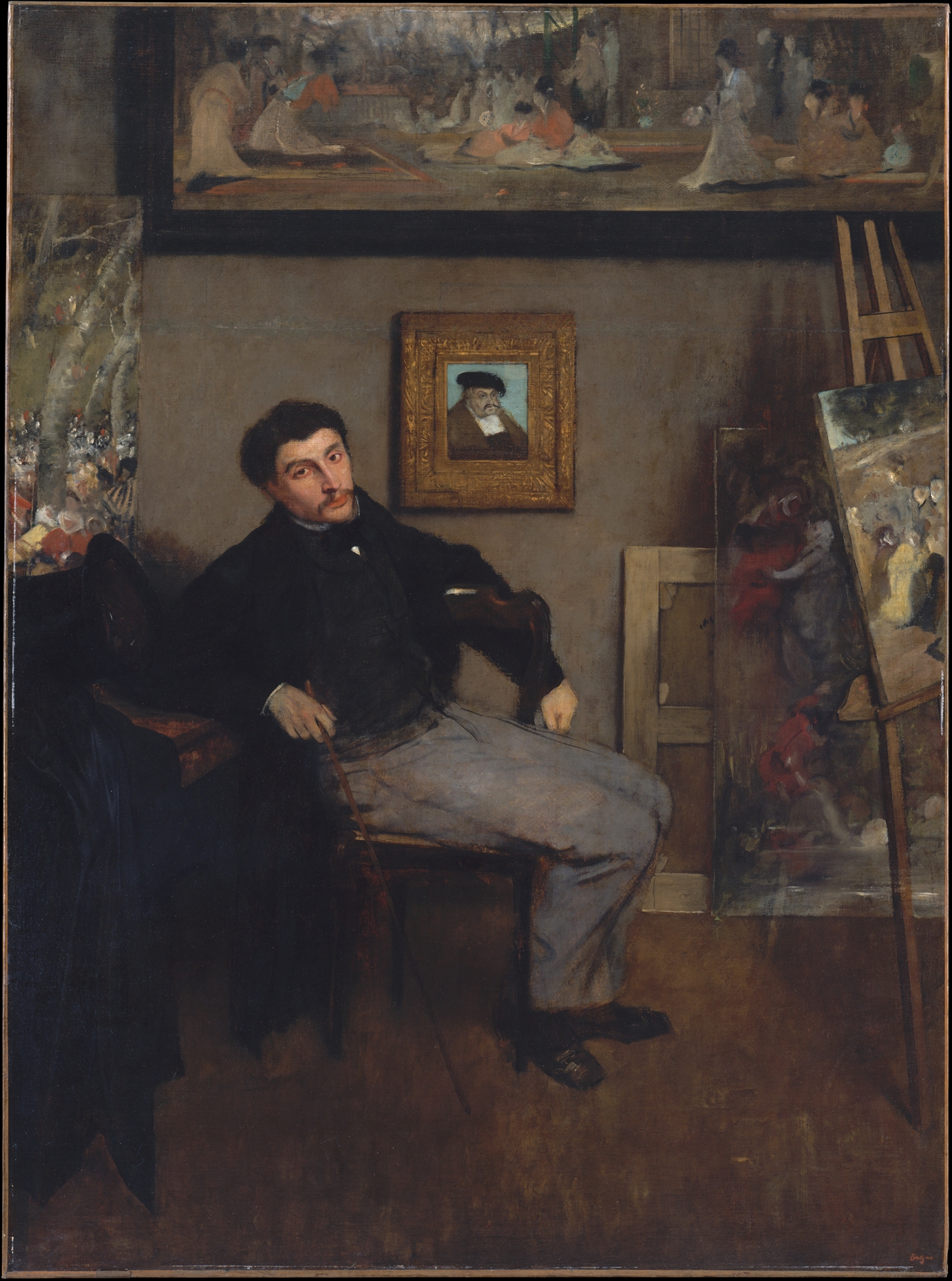

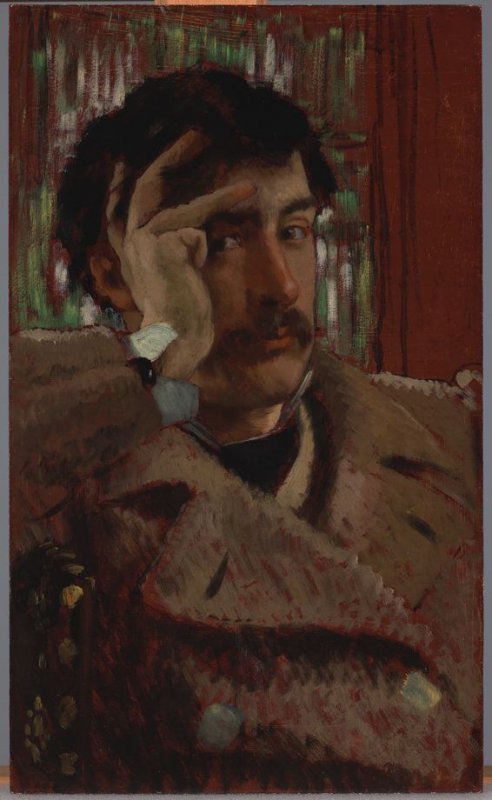

Arguably Tissot’s most significant artistic friendship during the years in which he painted the Getty canvas was with Degas. The two painters worked together in developing scenes of contemporary people in personal settings as subject matter for modern art and, especially, in exploring in their paintings the social and psychological state of Victorian women and to a lesser degree men.11 Both painters probed “the dark side” of female experience, with images of women in various states of melancholy, depression, and illness (fig. 5).12 Like Tissot, Degas had trained under Lamothe in the 1850s, and in paintings both informal and ambitious, the two painters can be seen to have actively responded to each other’s work throughout the 1860s. The Getty portrait may have served as a prototype for Degas’s pastel portrait of his sister Thérèse, Mme. Edmondo Morbilli (ca. 1869, private collection.)13 And the Musée d’Orsay Portrait of the Marquis and Marquise de Miramon and Their Children is clearly indebted to Degas’s Bellelli Family (1858–60; fig. 6) in the pose of the boy Léon with his leg tucked under his arm, the shallow friezelike organization of the figures, and their psychological isolation from one another. Degas’s ambitiously scaled portrait of Tissot (1868, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) shows a young handsome dandy, fresh off the Parisian boulevards, sitting in a painting studio (possibly his own), surrounded by copies of Japanese art, Baroque and German Renaissance painting, and contemporary genre (fig. 7. The composition is similar to Tissot’s Portait of Mlle L. L., exhibited at the Salon of 1864.14 The casual aloofness of the sitter is characteristic of Degas’s self-portraits of the period, and it has been suggested that this portrait of the painter in his studio represents Degas’s self-conception as an artist at the time.15 The portrait is sympathetic and familiar, and whether the painted copies hanging in the background belonged to Degas or to Tissot, they indicate shared artistic interests between two artists during a formative moment in their careers.

An unsigned note scribbled on the back of an envelope to Degas by someone responding to Degas’s Interior (also known as The Rape, 1868–69, Philadelphia Museum of Art)16 sheds light on the intimate artistic exchange between the two painters. The writer apparently dropped by Degas’s studio on rue de Laval, and, having missed him, hastily pens a response to Degas’s provocative work-in-progress. Extensive suggestions are made for the painting’s revision, and as Henri Loyrette points out, Degas seems to have followed some of the advice. The identity of the writer is not known conclusively, but both Loyrette and Theodore Reff suggest Tissot.17

That Degas and Tissot were close compatriots in an enterprise about which they were passionate is further supported by Degas’s correspondence to Tissot after the latter had left for London, In letters to his friend, Degas describes paintings he is working on and specific artistic challenges and ideas. One rather desperate letter of 1874 pleads with Tissot to participate in the first Impressionist exhibition:

Look here, my dear Tissot, no hesitations, no escape. You positively must exhibit at the Boulevard. It will do you good, you (for it is a means of showing yourself in Paris from which people said you were running away) and us too. . . . The realist movement no longer needs to fight with the others it already is, it exists, it must show itself as something distinct, there must be a salon of realists. . . . So forget the money side for a moment. Exhibit. Be of your country and with your friends. . . .18

For Degas, Tissot was very much a part of the young group generating la nouvelle peinture. With Tissot’s exhibition of the Two Sisters and Mlle. L. L. at the Salon of 1864, several critics applauded the painter’s break from medieval genre subjects to execute these “real paintings,” distinguished by their “sincerity of modern sentiment.”19 The critic Theophile Thoré discussed Two Sisters in the context of Manet and the réalistes, lauding Tissot for the naturalism of light and color, the modesty and simplicity of subjects, and the originality of his painting.20 Thoré commended Tissot’s break from his earlier medieval genre scenes, but was less positive when Tissot, in paintings such as The Confessional (1866) and Young Woman in a Church (1866), veered in influence toward his friend Alfred Stevens’s more anecdotal style.21

Tissot’s more anecdotal paintings were a conscious effort to play to the English market for such images, a strategy that came to dominate Tissot’s practice once he reached London. Alongside Stevens and Degas, and in fact most of the painters who would become Impressionists, Tissot kept a close eye on the English avant-garde, and he was specifically associated with John Everett Millais (1829–1896) and the Pre-Raphaelites and of course with his close friend Whistler.22 The reserved, tense psychological undertow of the de Miramon portraits are more in line, however, with Degas’s more complicated work. And Tissot is most successful when he avoids anecdote altogether and devotes himself instead to the increasingly dynamic genre of modern portraiture (fig. 8).23

Following his move to London, Tissot remained in touch with the Parisian avant-garde through correspondence with Degas, as well as through visits from Berthe Morisot (1841–1895) and Camille Pissarro (1831–1903), from whom Tissot bought a picture, perhaps in part to help the always penurious painter. Tissot and Manet traveled together to Venice in 1875, and Tissot bought a picture from him as well.24 For these struggling painters, Tissot’s financial success as a painter in London was inspiring, and they looked to him for help in placing their pictures in the English market. Although Tissot’s letters to Degas are not known, Degas’s published letters give the sense of unrequited communication. Degas eventually gave up on Tissot, perhaps disgusted by what he felt to be the London-based artist’s increasingly evident commercialism, by his refusal to participate in the Impressionist movement, by his impassioned return to the Catholic Church after his move back to Paris in 1882, and, finally, by Tissot’s sale in 1897 to Durand-Ruel of two painting Degas had given him.25 By all accounts Tissot was a difficult, unpredictable character, and his is among the more mysterious and complicated artistic biographies of the day.26 During the 1860s, however, he was deeply and consistently committed to the avant-garde project of reviving and redefining the great French tradition of painting.

- Mary G. Morton

-

For Tissot’s London career, see James Laver, “Vulgar Society,” The Romantic Career of James Tissot, 1836–1902 (London: Constable & Co., Ltd., 1936); Paintings, Drawings and Etchings by James Tissot, 1836–1902: Selected from an Exhibition Arranged by the Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield (London: Arts Counci1, 1955); Nancy Rose Marshall, “Transcripts of Modern Life: The London Paintings of James Tissot, 1871–1882” (PhD. diss., Yale University, 1997); Nancy Rose Marshall and Malcom Warner, James Tissot: Victorian Life, Modern Love (New Haven: American Federation of Arts, Yale University Press, 1999). On the biblical paintings, see J. James Tissot: Biblical Paintings, with essays by Yochanan Muffs and Gert Schiff, and a chronology by Michael Wentworth and David S. Brooke, exh. cat. (New York: Jewish Museum, 1982).

For Tissot’s earlier Parisian career, see Henri Loyrette’s treatment of Tissot in his discussion of Degas’s portrait of the painter in Jean Sutherland Boggs et al., Degas, exh. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1988), p. 130. In his extracanonical considerations, Robert Rosenblum has been much more interested. See his Paintings of the Musée d’Orsay, foreword by Françoise Cachin (New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1989) and his survey, 19th Century Art (New York: Abrams, 1974), pp. 357–60. For the most in-depth and serious exploration of Tissot as an artist, see Michael Wentworth, James Tissot (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984). ↩︎ -

Charles Baudelaire, “Le peintre de la vie moderne,” Le Figaro, Paris, 1863. In her book, Fashion in Art: The Second Empire and Impressionism (London: Zwemmer, 1995), Marie Simon includes the only published illustration of the Getty painting, outside the Sotheby’s catalogue in which the painting was briefly offered for sale in 1993, as an illustration of Baudelaire’s emphasis on fashion. ↩︎

-

Transcription:

Mon cher Miramon,

Que je vous compte mon embarrass, il faut que le 19 octobre j’ai envoyé au comité de l’Exposition universelle un tableau. Je n’serai point dans mon atelier, et n’ai pas le temps d’en faire d’ici là; et puis el en faudrait un d’une certaine importance pour figurer dignement à ce salon ou il y aura fort peu d’élus.

J’ai pensé au dernier portrait de madame de Miramon qui est certes ce que j’ai peint de plus avantageux et qui par sa nouveauté ainsi que par les initiales du livret (soit dit entre nous) serait je l’espère plus remarqué qu’aucun de mes tableaux, il est vrai qu’il attirera peut-être un peu trop les regards par son originalité, mais en somme tant mieux, et si vous voulez braver la publicité j’en serai enchanté et vous serai redevable des avantages que cette exposition pourra me procurer.

Ou ce billet vous trouvera-t-il? est-ce a Galliac en Anjou ou a Dieppe—voici en tout cas mon adresse J.T. au chateau de Buillon près Guingey (Doubs) et si vous consentez, cher ami, je vous serai fort oblige de cette nouvelle prevue d’amitié qu vous m’adresserez

Tout à vous

James Tissot

Mes hommages respectueux a madame de Miramon et sis le fou de Xavier est avec vous bien amities pour lui. ↩︎ -

Willard Erwin Misfeldt, “James Joseph Tissot: A Bio-Critical Study,” (PhD diss., Washington University, 1971), p. 66. His address is listed, however, in the Exposition Universelle catalogue in the entry for his two paintings as rue Bonaparte, 39. ↩︎

-

Susan Grace Galassi, in Whistler, Women, and Fashion, exh. cat, eds. Margaret F. MacDonald et al. (New York: Frick Collection, in association with Yale University Press, New Haven, 2003), p. 104. ↩︎

-

Ronald Anderson and Anne Koval, James McNeill Whistler: Beyond the Myth (London: J. Murray, 1994), p. 52. ↩︎

-

Thanks to Nancy Marshall for observations regarding Tissot’s participation in the aesthetic movement and his response to Whistler, August 2007. ↩︎

-

G. H. Fleming, James Abbott McNeill Whistler: A Life (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991), p. 127. ↩︎

-

In a letter to his mother in 1864, Rossetti describes Whistler’s chagrin at Mme De Soye, who raved about Tissot’s Japanese-themed paintings of the period, calling them “the three wonders of the world” (Denys Sutton, Nocturne, The Art of James McNeill Whistler [Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1963], pp. 47–48). ↩︎

-

On Whistler and fashion and modernism, see Margaret F. MacDonald et al. 2003 (note 5). ↩︎

-

Although Tissot focused more on middle- and upper-middle-class women, with Degas increasingly interested in working-class women, both artists painted pictures of sick and/or depressed women, producing images of individuals in various states of isolation, suffocation, and yearning. ↩︎

-

See, for example: Une veuve (1868), Mélancolie (1869), L’escalier (1869), and then of course Tissot’s lover in London becomes ill, Tissot’s La convalescente as a print and Getty drawing. And Degas’s Portrait of Estelle Musson Balfour (1863–65, Walters Art Gallery), Melancholy (late 1860s, Phillips Collection), The Convalescent (1868–87, Getty Museum.) ↩︎

-

Michael Wentworth, James Tissot 1984 (note 1), p. 62. ↩︎

-

Michael Wentworth, James Tissot: Catalogue Raisonné of His Prints (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1978), p. 48. ↩︎

-

Theodore Reff, “The Pictures within Degas’s Pictures,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 1, no. 1 (1968), p. 135. Henri Loyrette reads the portrait as a representation of the painter caught between innovation and fashion, characterized by curiosity, sympathy, envy, and irony on Degas’s part. Loyrette’s low opinion of Tissot as an artist, of his “pleasant and mundane” portraits, may be affected by Tissot’s later London career (Loyrette 1988 [note 1], p. 130). See also Nancy Marshall’s entry on Tissot’s self-portrait in Marshall and Warner 1999 (note 1), p. 53. ↩︎

-

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, n.a. fr. 24839, published in English in Theodore Reff, Degas: The Artist’s Mind (London: Thames and Hudson, 1976), pp. 225–26. Reprinted in Loyrette’s entry in Degas 1988 (note 1), pp. 143–46. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas, Degas Letters, ed. Marcel Guerin, trans. Margeurite Kay (Oxford: B. Cassirer, 1947), pp. 38–39. For the French, see Cyrille Sciama, James Tissot et ses maîtres (Nantes: Musée des Beaux-Arts, and Paris: Somogy, 2005), p. 39. ↩︎

-

Léon LaGrange, “Le Salon de 1864,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 16, no. 6 (June 1, 1864), pp. 524–25. LaGrange focuses on Two Sisters in particular, which he singles out as one of the best paintings of the Salon. ↩︎

-

Thoré, Salons de W. Burger, 1861 à 1868 (Paris: Renouard, 1870), pp. 100–102, 199–201. ↩︎

-

Ibid, pp. 200, 488. ↩︎

-

Ibid, pp. 200–201. See too Paul Mantz, “Salon de 1865,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 19, no. 1 (July 1, 1865), pp. 11–12, in which he refers to the originality, strangeness, and audacity of paintings like Two Sisters (1864) and Spring (1865). Also Hector de Calias, “Salon de 1861,” L’Artiste 12 (July 15, 1861), p. 29. ↩︎

-

For portraiture as a genre of radical innovation during the Second Empire and Third Republic, see Sona Johnston, Faces of Impressionism: Portraits of American Collections, exh. cat. (New York: Rizzoli, 1999). ↩︎

-

Wentworth 1984 (note 1), p. 18. ↩︎

-

See Guerin 1947 (note 18). The painting, according to Loyrette 1988 (note 1), p. 263, was Woman with Field Glasses (1875–76, Dresden Gemäldegalerie Neue Meister.) ↩︎

-

This characterization is established biography at least as early as 1937: “My readers probably know very little about Tissot, that mysterious forgotten figure, ill-judged for complex reasons” (Jacque-Emile Blanche, Portraits of a Lifetime: The Later Victorian Era, The Edwardian Pageant, 1870–1914, trans. and ed. Walter Clement [London: J. M. Dent, 1937], p. 25). ↩︎