Around 1764, French artist Jean-Baptiste Pillement painted this lively, imaginary marketplace meant to evoke a fantasy of the “Orient,” a term historically and broadly used for Asia. “Orient” derives from the Latin word for East, oriens, and refers to Asia’s geographic location relative to Europe. Pillement’s career and this painting captures the 18th century fascination with foreign, particularly Asian, cultures, which could be both admiring and derogatory.

Here, three groups of dancers perform in an open space framed by bustling stalls and lush tropical trees to the left and right. Merchants go about their business, conversing with one another, surveying their goods, and looking at the performers. In the center of the market, a man dances, holding a bell in each of his hands. Slightly in front of him on either side are two groups, each composed of three dark-complexioned dancers with cymbals. These characters are all balanced on one foot, caught mid-step in their energetic performance.

The variety of ethnic types in this scene—suggested by the costumes, skin tones, and exaggerated facial features—contributes to the idea that this is a port where people from different places interact. The man in blue holding scales in the front left appears to be a Chinese caricature by his cap and pointed beard, while the group in the back left seems to be of Turkish origin by the crescent moon atop their tent. Most people are wearing loose-fitting clothing and some wear turbans or headscarves, but it would be difficult to conclude where these people are specifically from or where this scene is taking place, though the locale is clearly differentiated from Europe.

At this moment, Europeans were particularly fascinated by Asian designs and customs due to a steady increase in travel, trade, and diplomacy with previously isolated or inaccessible regions of Asia. Imports like porcelain, lacquer, and textiles had become more available and in demand, and published accounts from missionaries and travelers provided abundant imagery for artists to draw upon and imitate.1 Like most Europeans, Pillement had a limited and secondhand understanding of foreign cultures and in his depictions of Asia he sometimes grouped and confused different cultures and people under the umbrella-term of “Oriental.” This widely-used label was applied to many regions east of Europe, including China, Japan, North Africa, and Turkey, and is used in quotation marks in this essay to refer to this imagined idea of Asia. The popular aesthetic for what was considered exotic was all around Pillement in visual representations on canvases, tapestries, and furniture, as well as onstage in theatre and dance. This painting, probably depicting a ballet, embodies these common contemporary portrayals of Asia and reflects the European desire for “Oriental” decoration.

Scholars and dealers have suspected this composition to be a design for a ballet or theatrical performance dating back to its first known publication under the title Le Ballet in 1867.2 The openness of the middle seems natural for a stage while the hazy port behind it acts as a static backdrop. The way the stalls flank either side, extending into the viewers’ space, evokes a theater’s proscenium, the area in front of the curtain framing the stage. The emphasis on perspective, exaggerated in the receding tile floor, would also add the illusion of depth to the stage space.

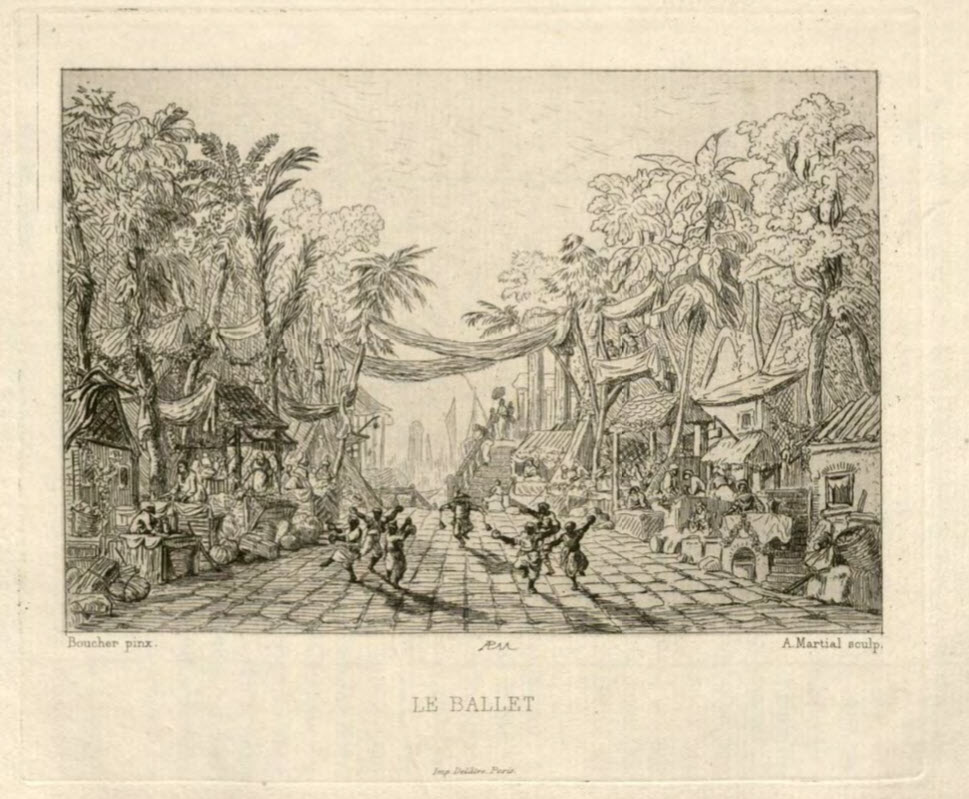

In 1867, this work was published in a book of etchings of three paintings attributed to François Boucher (1703–1770) (fig. 1).3 In this text, French art critic Ernest Chesneau praised the composition and claimed it to be an important document for a “certain neglected art history, that of scenic decoration.”4 He speculated that this scenery was intended for the Paris Opera or Fontainebleau court theater, where Boucher had worked, and cited a few possible performances from the 1730s and 1740s with “Oriental” themes, of which there were many.5 Boucher’s best-known set design was for Jean-George Noverre’s popular ballet, Les Fêtes Chinoises; he based this design on oil sketches he had previously made for the Beauvais tapestry series La Tenture Chinoise. La Danse Chinoise (fig. 2) from the series depicts a performance for a Chinese emperor, and Boucher’s costumes, characters, and instruments undoubtedly influenced the younger Pillement’s representations of Asia.6

Pillement’s career was similar in many ways to Boucher’s, perhaps leading to the misattribution. Like Boucher, Pillement produced decorations for the theatre and royal interiors, designed tapestries, and was a tastemaker of chinoiserie. Though Pillement travelled widely in Europe—he left his home in Lyon when he was seventeen and spent his life between various capitals under royal appointments and other patronage—his knowledge of Asia was only secondhand through other European depictions like Boucher’s tapestry series and some contact with imported Asian goods. In his widely-reproduced chinoiserie designs, he relied on his imagination, indulging decorative flourishes and whimsy more than accuracy.7 These designs are often character, architectural, or floral studies, rather than comprehensive compositions, so Market Scene is unusual in Pillement’s oeuvre for being a fully fleshed-out “Oriental” setting.8 Among his oeuvre of mainly pastoral and coastal landscape paintings, two undated monochromatic canvases capture Asian subjects in as much detail as the Getty’s composition (figs. 3 and 4); they both depict opulent, fantastical royal processions with characters in a variety of costumes, accompanied by elephants and camels.9

Pillement likely painted Market Scene around 1764, when he was in Vienna working for the Holy Roman Emperor Francis I (1708–1765) and Empress Maria Theresa (1717–1780). Between 1763 and 1765, Pillement contributed to several decorative projects at the palaces of Schönbrunn and the newly built Blauerhof, and also drew theatrical costumes for court performances.10 However, no payment records from these sources exist to help trace this painting.11 Pillement’s costume studies, now in the Albertina, may have been proposals presented to the imperial family, great lovers of the theatre. One chalk drawing, signed and dated 1764, depicts a Chinese man with the same type of facial hair and baggy clothing, holding a similar bell instrument as the Getty painting’s central dancing figure (fig. 5).

Music historian Bruce Alan Brown has identified Giuseppe Salomoni’s ballet Un Port de mer dans la Provençe, performed in Vienna’s Kärntnertortheater in August of 1763, as the subject of Pillement’s painting.12 Brown deems it unlikely that Pillement was the scenic designer for Salomoni’s ballet, since he is never mentioned in the theater payment records, but Pillement could have seen the production and been inspired by the set decoration. Brown’s theory relies on an account from Philipp Gumpenhuber, the assistant director of the Burgtheater ballet company who took copious notes on performances. Gumpenhuber described this 1763 performance:

In the decoration of this ballet one sees several vessels at the shore, and many people busy unloading a number of bales of merchandise. Several women are in their boutiques situated on the land to one or the other side, in order to buy or sell, which makes for a pretty view. After having worked, the ones and the others [the buyers and sellers] are taken with a desire to divert themselves, and form a general dance which is the start of this completely merry and diverting ballet. As seaports are always abounding with people of every nationality, [in this] ballet one will have the charm of variety of several characters who will appear in it. A sailor of the country, wishing to amuse himself, plays some tricks on an unsuspecting young girl. After a minor quarrel, they are soon reconciled, and this ballet ends as merrily as possible, with the accompaniment of instruments appropriate to the country one aims to represent.13

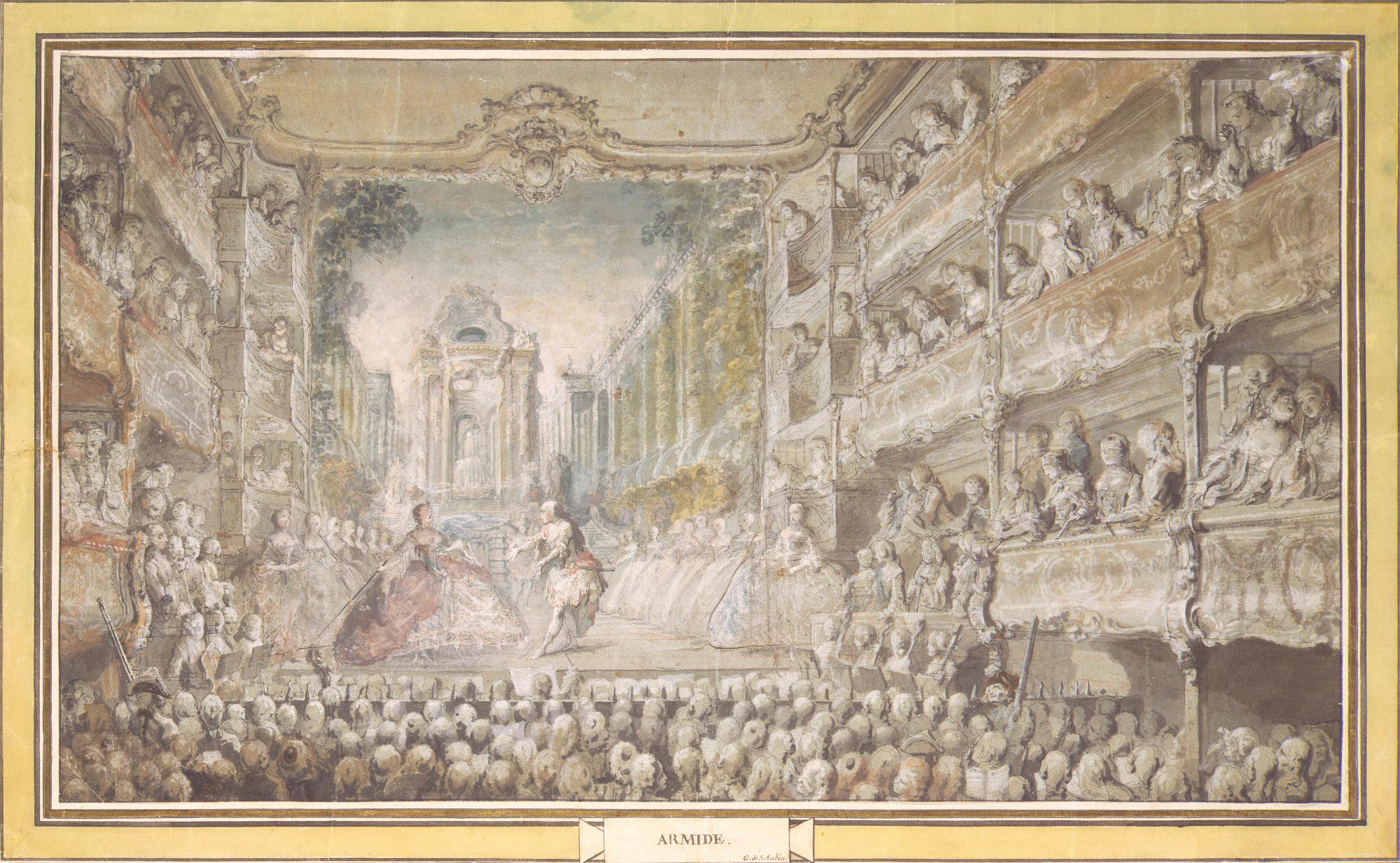

Without corroborating archival documents, it is difficult to confirm if Pillement’s painting depicts Salomoni’s ballet, or if it is documenting or proposing a different production. Scenery designs by Pillement are not known today and few designs even from an artist as successful as Boucher survive either. One canvas by Boucher of a quaint country village set is now at the Musée de Picardie in Amiens (fig. 6), and a design that is likely Boucher’s for the Paris Opera performance of Armida was sketched by Gabriel de Saint-Aubin in 1761 (fig. 7).14 Works on paper from French contemporaries who devoted their careers to theatre design, like Louis-René Boquet (1717–1814), are more abundant and demonstrate stage decoration and costume design of this period, but Pillement’s own work in the theater is difficult to define.15

As fanciful as Pillement’s imagination could be, he likely would have seen a performance like this one, in which foreign peoples were represented onstage. At Vienna’s French theater, one-act ballets focusing on specific cultural groups were popular, and the ópera-ballet genre featured short entrées, which presented a succession of “ethnic culturescapes,” often crudely and humorously differentiated from European courtly styles of dancing.16 Musicology scholar Ralph P. Locke remarked upon this painting, “The movements of all these foreign dancers are worlds apart—as we say—from the firmly erect ‘noble’ styles of European courtly ballet. The percussive clangor from the dancers, similarly, contrasts with the silence that aristocrats largely maintained when participating in, say, a courtly ballet.”17 The dark-skinned dancers, mid-dance with cymbals in hand, embody this difference and command a central position in this painting, but they have not been paid much heed, receiving only passing reference in the literature.18

Pillement frequently depicted Chinese, Turkish, and other “foreign” types, but he rarely showed dark-skinned characters; this painting might be the only work in his oeuvre to do so. Their presence here may testify to an actual performance involving dark-skinned or, more likely, blackface-wearing dancers that Pillement witnessed, rather than imagined. European performers would often imitate foreign peoples onstage, but Black Africans also existed in courts, as servants, musicians, or attendants who added status and intrigue to the court.19 Scholar of Afro-German history Peter Martin estimated there were four to five thousand people of Black African descent in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century German lands.20 Yet, few would be part of professional dancing troupes in Europe, making it more likely the dancers here are costumed in imitation of other cultures. Brown believes all characters in this painting to be played by European dancers of the grotesque style in the Vienna Kärntnertortheater ballet company.21

Though the subject of the painting is still not conclusively identified, Pillement’s Market Scene remains a unique reflection of eighteenth-century interest in the “Orient” in visual and theatrical art—an aesthetic that interpreted and appropriated motifs from foreign cultures as exposure via trade and diplomacy increased, both illuminating and distorting the world beyond Europe.

- Nicole Block

-

For an introduction to chinoiserie and Oriental decoration of this period, see Une des provinces des Rococo: La Chine rêvée de François Boucher, exh. cat. (Besançon: Musée des beaux-arts, 2019); Isabelle Tillerot, Orient et ornement: l’espace à l’œuvre ou le lieu de la peinture (Paris: Fondation maison des sciences de l’homme, 2018); Francesco Moreno, Chinoiserie: The Evolution of the Oriental Style in Italy from the 14th to the 19th Century (Florence: Centro Di, 2009). ↩︎

-

The painting was titled Le Ballet in Trois tableaux de F. Boucher (Paris: Cadart & Luquet, 1867), Un Ballet Oriental in Exposition de la Turquerie au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Palais du Louvre, 1911), and then Divertissement Oriental in Succession de Madame Heidelbach (1933) up to its sale to the Getty in 2003. Divertissement (“entertainment” or “distraction”) refers to a segment of an opera, so the title has kept its theatrical connections until the Getty Museum’s acquisition when it was given the descriptive title, Market Scene in in Imaginary Oriental Port. ↩︎

-

Trois tableaux de F. Boucher 1867, pp. 5–6, ill. ↩︎

-

“L’œuvre est aimable, vivante, d’un coloris fluide, harmonieux, léger. Il s’y ajoute aussi un autre intérêt. Elle est un document interessant pour l’histoire d’une certain art histoire négligée, ignorée jusqu’à ce jour, celle de la décoration scénique.” Trois tableaux de F. Boucher 1867, p. 5. ↩︎

-

The footnote to the text on “Le Ballet” lists performances that could fit this composition’s ambiguous setting: “Almasis, ballet, 1748. Les Indes galantes, 1735, repris fort souvent. Zaide, reine de Grenade, 1739. Les Fêtes de l’Hymen et de l’Amour, 1747, etc. etc.” Trois tableaux de F. Boucher 1867, p. 6. ↩︎

-

Pillement would have been familiar with Boucher’s tapestry designs from his training at the Gobelins tapestry manufactory. See the most recent monograph on Pillement, Maria Gordon-Smith, Pillement (Cracow: IRSA, 2006), pp. 26, 34, 36. ↩︎

-

Gordon-Smith 2006, pp. 36, 38. ↩︎

-

For an overview of Pillement’s decorative work, see Maria Gordon-Smith, “The Influence of Jean Pillement on French and English Decorative Arts Part One,” Artibus et Historiae 21, no. 41 (2000). ↩︎

-

For these two canvases, see Gordon-Smith 2006, pp. 48–51. The iconography seems related to Mughal miniatures decoupaged by the imperial family for Schönbrunn Palace during the same time as Pillement’s tenure. See Aaron Hyman, “The Habsburg Re-Making of the East at Schloss Schönbrunn, ‘or Things Equally Absurd,’” Art Bulletin 101, no. 4 (December 2019). ↩︎

-

For more about Pillement’s time in Vienna, see Maria Gordon-Smith, “Jean Pillement at the Imperial Court of Maria Theresa and Francis I in Vienna (1763 to 1765),” Artibus et Historiae 25, no. 50 (January 2004), pp.187–213. ↩︎

-

This lack of records can possibly be explained by the fact that court performances were considered private matters and not recorded in the same way as Vienna’s other theatres, Gordon-Smith 2006, p. 119. ↩︎

-

Bruce Alan Brown, “Magri in Vienna: The Apprenticeship of a Choreographer,” in The Grotesque Dancer on the Eighteenth-Century: Gennaro Magri and His World (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2005), pp. 86–87. ↩︎

-

Brown quotes and translates from Gumpenhuber’s papers in French at Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Musiksammlung, Mus. Hs. 3458oa-c and Harvard University, Theatre Collection, MS Thr. 248-48.3. See Brown 2005, pp. 87–88. ↩︎

-

Boucher’s stage design is discussed at some length in Ellen G. Landau, “‘A Fairytale Circumstance’: The Influence of Stage Design on the Work of François Boucher,” The Bulletin of Cleveland Museum of Art 70, no. 9 (November 1983). ↩︎

-

Many of Boquet’s costume designs can be seen online in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France Gallica database. ↩︎

-

Ralph P. Locke, Music and the Exotic: From the Renaissance to Mozart (2015), pp. 232, 274–76. ↩︎

-

Ibid., p. 277. ↩︎

-

The dark-skinned figures are referred to as “Maures” (Moors) in Trois Tableaux de F. Boucher 1867, but otherwise not mentioned in the other literature until 2005. The ethnic representations seen in this painting are discussed in relation to music history in Brown 2005 and Locke 2015. ↩︎

-

See Rashid-S. Pegah’s chapter, “Real and Imagined Africans in Baroque Court Divertissements,” and Anne Kuhlman’s chapter, “Ambiguous Duty: Black Servants at German Ancient Regime” in Germany and the Black Diaspora: Points of Contact, 1250 – 1914 (New York: Bergahn Books, 2013). ↩︎

-

Kuhlman cites Peter Martin’s paper presented at the conference, Black Diaspora and Germany across the Centuries at the German Historical Institute, in Washington DC on March 20, 2009, “Black Diaspora Studies in Germany: Some Remarks to the State of the Art at the Washington Conferences,” Germany and the Black Diaspora: Points of Contact, 1250 – 1914 (2013), p. 63, footnote 26. ↩︎

-

Brown 2005, p. 88. ↩︎