For the Sienese master Domenico Beccafumi, even the smallest devotional scenes provided an opportunity for presenting compelling stories. This painting and its companion piece illustrate two central episodes from the miraculous life of the Dominican mystic Saint Catherine of Siena (1347–1380). The panels, which are similar in style and palette, and nearly identical in size, were once likely part of the same larger ensemble, probably an altarpiece predella. Among the earliest representations of Saint Catherine completed by Beccafumi, they showcase the artist’s exceptional ability to create highly expressive and engaging narratives.

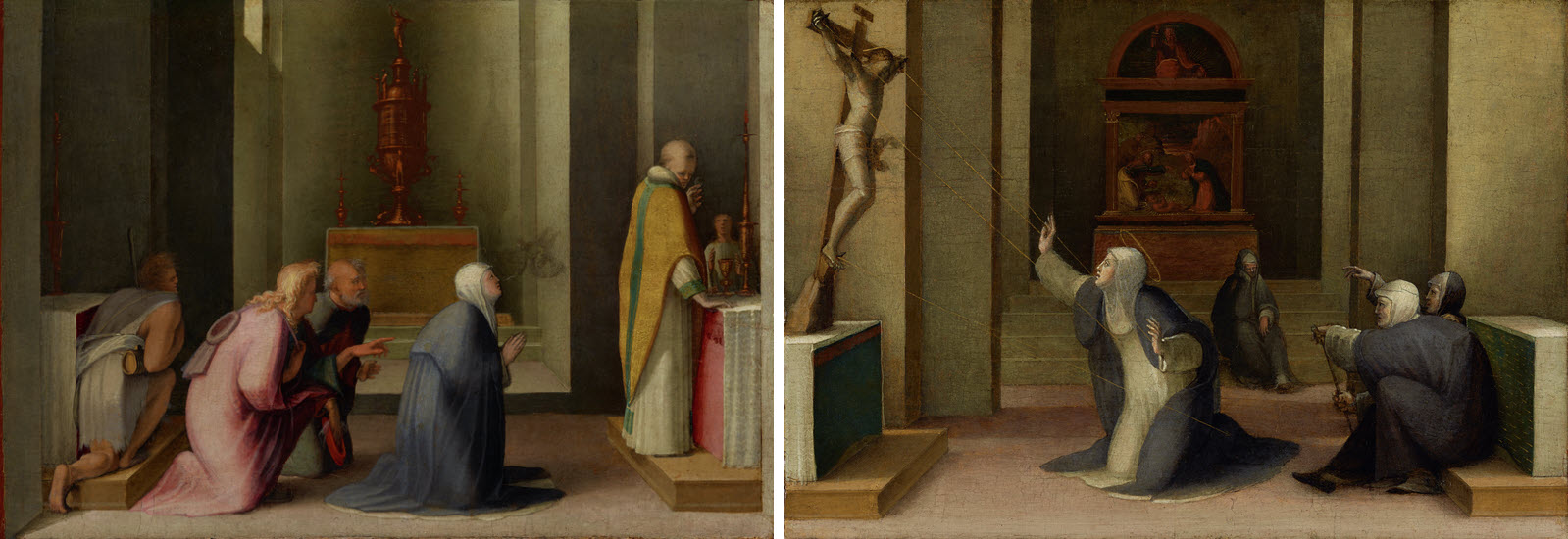

In Saint Catherine of Siena Receiving the Stigmata (97.PB.25, above right), Catherine appears in a state of ecstasy, her arms dramatically outstretched, her body pierced by the beams of light that inflicted upon her the sacred wounds of Christ. The saint’s transcendent experience is validated by the presence of her companions who, incredulous, witness the scene. Astonished spectators also observe Catherine in The Miraculous Communion of Saint Catherine of Siena (97.PB.26, above left) as she mysteriously receives the sacrament of the Eucharist from an angel. The diaphanous spirit, delicately painted, delivers a fragment of the Host directly into the mouth of the saint fig. 1, while the surprised priest holds the remainder of the consecrated bread in his left hand. Through light effects and chromatic contrasts, Beccafumi constructed realistic spaces in which these powerful narratives unfold.

A relentless drive for innovation defined the career of Beccafumi. Over the course of his life, the artist challenged himself in a variety of media, from painting and printmaking to bronze sculpture. His style constantly evolved, experimenting with light, color, and form, and engaging with the novelties developed by his contemporaries, including Fra Bartolomeo (1472–1517) and Raphael (1483–1520).1 In the early years of his career, following a period in Montepulciano (c. 1507) and a first visit to Rome (1510–1511/1512), Beccafumi returned to his native Siena, where he established his workshop and painted, probably around 1513, the two Getty panels.2 In the Cinquecento, Siena was a medium-sized city, without the economic or political influence of major neighboring centers like Florence, but that cultivated a strong civic identity and took great pride in its landmarks, artists, and saints.3 Beccafumi enjoyed wide popularity in Siena, assuming the role of “civic artist” and contributing to almost every major public and ecclesiastical project undertaken in the city.4 In a well-known passage, the biographer and painter Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) recalled how Beccafumi once confessed to him that “away from the air of Siena and from certain comforts of his own, he [Beccafumi] did not seem to be able to do anything.”5

In the Getty paintings, Beccafumi confronted a subject that was well established in Sienese devotional and artistic tradition. One of the city’s most beloved patron saints, Catherine, like Beccafumi, was Sienese. Born in 1347, she was one of twenty-five children born to Giacomo di Benincasa, a wool dyer.6 From a young age, Catherine claimed to have experienced miraculous visions and states of trances that allowed her to enter in direct contact with God.7 When she was seven years old, she took a vow of chastity and, at the age of sixteen, she joined the Sisters of Penance of Saint Dominic (a group of laywomen affiliated to the Dominican Order). The reputation of Catherine’s mystic experiences and charitable work grew rapidly and she soon reached international fame, becoming one of the first female religious figures to have an influential role in matters of capital importance, including the Crusades and the Great Schism of the Western Church (1378–1417).8

The miraculous events that marked Catherine’s life are narrated in the biography of the saint written by her disciple and spiritual confessor, Raymond of Capua (1330–1399).9 Among the numerous mystic visions meticulously described by Raymond’s account are those depicted by Beccafumi in the Getty paintings. While in Pisa in 1375, Raymond recalled that following the celebration of mass “[Catherine’s] emaciated body, which had been prostrate on the ground, rose up to a kneeling position; she stretched out her arms and hands to their full length [as in the Getty Stigmata]; her face grew radiant […] then […] she pitched forward on the ground as if she had received a mortal wound. A few minutes later she returned to her senses.”10 During her moment of ecstasy, Catherine told Raymond that she saw Christ on the Cross coming towards her and five rays of blood (depicted in gold in the Stigmata) emanating from his wounds and connecting to her hands, feet, and heart. On another day, during a mass he personally celebrated, Raymond (portrayed at the far right in the Communion) recalled that a part of the sacred Host he had just broken suddenly fell on the altar and, despite his attempts to find it, inexplicably disappeared. Preoccupied, he later turned to Catherine who had been ill and incapable of attending the mass. The saint, who “could not restrain a smile,” admitted that the Host’s piece had not mysteriously vanished but had been brought to her directly by Jesus Christ (shown in the form of an angel in the Communion panel, fig. 1).11

Catherine died in April 1380 and almost immediately became the object of a widespread cult.12 Her image and the representations of her miracles as told by Raymond started to be celebrated in the works of contemporary artists, especially in Siena. In her native city, Catherine was not only considered a venerable figure, but also a fellow citizen: her life, and later her canonization (1461), became a source of civic pride. Around the time of Catherine’s sanctification, Lorenzo di Pietro (known as Vecchietta, 1410–1480) painted a full-scale fresco of the saint to exhibit in the city’s Palazzo Pubblico; in the same years, Giovanni di Paolo (1393/1398–1482) produced a series of ten panels for the church of Santa Maria della Scala (the state hospital and one of its main civic institutions), which illustrated the key episodes of Catherine’s life, including the Miraculous Communion and Receiving of the Stigmata fig. 2.13 Devotional images involving the saint continued to proliferate in the following decades in Siena, involving new generations of local artists, such as Bernardino Fungai (1460–1516), and eventually Beccafumi.

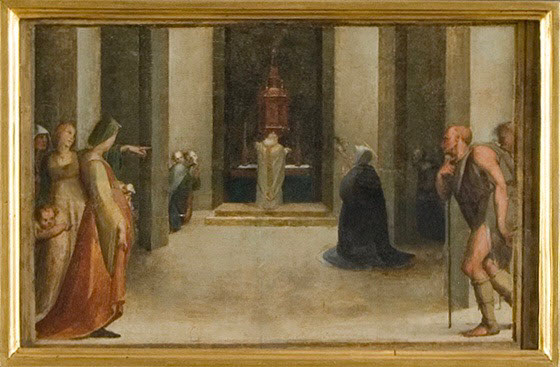

In painting the Getty panels, Beccafumi relied on some of the motifs developed by his predecessors. A fascinating example is offered by a small scene (c. 1505) completed by the Sienese painter Girolamo di Benvenuto (1470–1524), today in Denver fig. 3.14 Girolamo portrayed Catherine prostrated in front of an altarpiece (right) in the act of liberating a possessed woman from a demon (left). For his two paintings, Beccafumi employed the same frontal perspective and similar architectural setting adopted by Girolamo, and also extrapolated some specific details, such as the kneeling young man with the wooden flask on the right, closely recalling the kneeling figure at the far left of the Getty Communion.

However, Beccafumi also strove to find new ways to make the traditional subject of Catherine’s life engaging and compelling for his contemporary audience. Using a limited, almost monochrome, palette of greys and browns and sharp contrasts of light and shadow, the artist created in both the Stigmata and the Communion realistic and austere church interiors, which act as neutral, intimate backgrounds for the unfolding events. Beccafumi enhanced the narrative power of the episodes by introducing evocative details and emphatic gestures: the broken Host held by the puzzled Raymond in the Communion fig. 4, the pointing fingers of the witnesses gathered nearby, and, in the Stigmata, Catherine’s wide-open arms and Christ’s flying drapery, which infuses dynamism to the leaning crucifix fig. 5. By including witnesses in the scenes, Beccafumi conferred further veracity to the miraculous events experienced by Catherine. While, in the years before, artists such as Giovanni di Paolo had represented, for instance, Catherine alone when receiving her stigmata fig. 2, leaving the viewers in doubt as to whether they were looking at an apparition or a real event, Beccafumi ingeniously merged the saint’s internal vision with the “external” experience of the surrounding figures, blurring the line between the spiritual and earthly dimensions.

To further engage viewers and render his scenes more convincing, Beccafumi also included in his paintings reproductions of artworks that would have been well known to his fellow citizens. The altarpiece depicted in the background of the Stigmata resembles, for instance, the nativities painted some years previous by Girolamo di Benvenuto and Francesco di Giorgio (1439–1501),15 while the tabernacle visible in the Communion alludes to the bronze ciborium (a container for the sacred Host) designed by the Sienese artist Vecchietta fig. 6.16 Measuring more than 13 feet high, Vecchietta’s monumental ciborium (1467–1472) was a widely celebrated object in Siena, and stood (after 1506) on the high altar of the city’s Cathedral. By depicting these renowned works, Beccafumi introduced a sense of familiarity into episodes from a distant past, translating the mystic events of Saint Catherine’s life to a contemporary and quintessentially Sienese setting, which would directly and easily involve his audience.

Far from being subsidiary parts of his works, Beccafumi labored over the production of his small-scale narratives. The artist planned each detail in the Stigmata and Communion scenes carefully and executed them with great precision. Technical analysis revealed the presence in both panels of underdrawings and traces of preliminary painted sketches – visible, for instance, in Catherine’s garments in the Communion and in the kneeling figure in pink.17 Before starting to paint, Beccafumi meticulously set out the scenes by drawing directly on the prepared panel using black chalk and a liquid medium applied with a brush. He likely followed preparatory drawings, today lost, and made only minor changes to the composition during the painting process. He also employed tools, such as rulers and a compass, to create the architectural space and obtain perfect straight lines and round shapes. In the Stigmata panel, one can still see the hole where Beccafumi placed the end of the compass used to draw the semi-circular arch of the background altarpiece fig. 7. The refinement that Beccafumi conferred on his smaller works elicited the praise of contemporary patrons as well as later biographers. Vasari admired the “boldness and vivacity” of Beccafumi’s “little scenes,” while the scholar and writer Luigi Lanzi (1732–1810), who did not particularly like the work of Beccafumi, still appreciated the artist’s skill in painting details, noting that his style “resembles a liquor which retains its qualities when shut up in a phial, but evaporates when poured into a larger vessel.”18

In the years following the Getty paintings, Beccafumi produced other works featuring Saint Catherine and her extraordinary life.19 Among these is the Stigmatization altarpiece (c. 1513–1515) for the Olivetan monastery of San Benedetto outside Porta Tufi in Siena fig. 8 which shows remarkable similarities with the Getty panels:20 the main scene develops on a large scale the composition of the smaller Stigmata, replicating some of its features, such as Catherine’s kneeling pose and outstretched arms, and the nun asleep in the background.21 Like the Getty Communion, the central panel of the predella of the Stigmatization altarpiece depicts Catherine receiving the Host from the angel in a comparable church setting, but from a different vantage point fig. 9. Interestingly, the architectural backdrops of the Stigmatization predella and central scene were established, as in the Getty panels, with carefully incised lines.22 The connections with the Stigmatization altarpiece helped to confirm the attribution of the Getty paintings to Beccafumi and date them to around 1513–1515.23 The sharp outlines, rational perspectives, and balanced compositions of the two panels are consistent with other works by Beccafumi from the 1510s, namely the Trinity tryptic for Santa Maria della Scala (c. 1513). Specific details of the paintings, such as the muscular body of the kneeling figure at the far left of the Communion, suggest the stimuli – namely Michelangelo and antique models – that the artist would have encountered during his trip to Rome immediately before painting the two panels.24

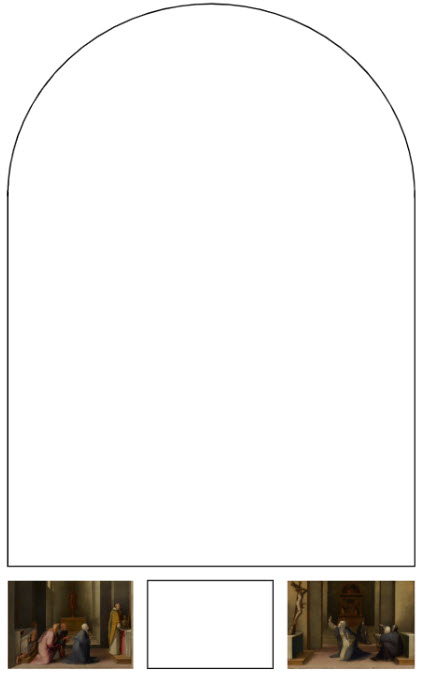

The Stigmatization altarpiece also provides insight into the original configuration of the Getty paintings. In all likelihood, the Stigmata and Communion were part of a multi-part predella which served as the base of an altarpiece. Depending on the size of the central painting, the predella was composed of three or more panels, perhaps illustrating other episodes from the life of Catherine. The altarpieces produced by Beccafumi over the years show a great diversity in the configuration of their predella, ranging from multiple scenes of similar scale, as in the case of the Santo Spirito altarpiece (c. 1528), to panels of diverse size and subjects, as in the altarpiece completed for the Oratory of Saint Bernardino of Siena (c. 1535–1537).25 Given their specular compositions and close similarities, the two Getty paintings may have functioned as complementary components within the predella. For example, the two panels may have been positioned to either side (the Communion on the left and the Stigmata on the right) of a central scene fig. 10. In this arrangement, the resulting predella would have closely resembled the tripartite base of the Stigmatization altarpiece fig. 8.26 If this were the case, the original altarpiece and its predella would have been relatively modest in scale, closer to the small paintings produced by Beccafumi for monastic interiors, such as the Nativity of the Virgin for the nuns of San Paolo (c. 1530), than to the monumental works he painted for the above-mentioned Dominican church of Santo Spirito and Saint Bernardino.27

Nothing is known of the original location of the altarpiece to which the Getty panels once belonged. In connection with the growing cult of Saint Catherine, new devotional sites dedicated to the saint multiplied in Siena between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries: churches, chapels, and monasteries were founded in Catherine’s name and even her old house and her father’s wool-dying workshop in the neighborhood of Fontebranda were turned into a venerated sanctuary. Conversely, scenes from the life of Catherine were included in numerous altarpieces commissioned by private patrons and religious institutions of the city. Beccafumi was very active in the production of altarpieces and several Sienese churches and new Catherinian shrines once preserved works that the sources attributed to him.28 Very few altarpieces by the artist, however, today remain in their original locations. Many were disassembled during the following centuries, and their components dispersed, often separately, in private and museum collections in Siena, and across Europe and the United States.29 Thus far, neither the main painting nor additional predella panels flanking the Stigmata and the Communion have been identified, and their original location remains difficult to determine without further documentary and visual evidence.

Saint Catherine, a figure inextricably interwoven in local cult and civic pride, was the protagonist of many of the devotional images produced by Beccafumi and his Sienese colleagues during their careers. For Beccafumi, an indefatigably inventive artist, the incessant demand in Siena for the representations of the saint presented the opportunity to continuously experiment, vary, and develop a theme already well-rooted in local tradition. In the Stigmata and Communion panels, Beccafumi deftly devised new and original ways to keep Catherine and her miraculous achievements alive and a participant in the lives of his contemporary Sienese citizenship. Though small in size, Beccafumi’s panels epitomize the exceptional narrative skill of their author and encapsulate the story of a city, its artistic tradition, and civic saint.

- Saida Bondini

-

On Domenico Beccafumi see Donato Sanminiatelli, Domenico Beccafumi (Milan: Bramante Ed., 1967); Piero Torriti, Beccafumi: l’opera completa (Milan: Electa, 1998); Giovanni Agosti, ed. Domenico Beccafumi e il suo tempo, exh. cat. (Milan: Electa, 1990). On Beccafumi’s journeys and his encounters with artists, see Silvia Ginzburg, “Viaggi e aggiornamenti in Beccafumi,” Annali di studi umanistici 5 (2017), pp. 157–188. ↩︎

-

The early years of Beccafumi’s career in Montepulciano and Siena (1500s), hitherto undocumented, have recently been clarified by Andrea Giorgi, “Montepulciano 1507: il podestà Lorenzo Beccafumi e Domenico di Jacomo” and Alessandro Angelini, “Gli inizi di Beccafumi e il gonfalone con la Santa Agnese del 1507,” in Cecilia Alessi, ed. Il buon secolo della pittura senese: dalla maniera moderna al lume caravaggesco, exh. cat. (Pisa: Pacini Ed., 2017), pp. 16–23 and pp. 29–38, respectively; Alessandro Angelini and Marco Fagiani, eds. Il Giovane Beccafumi e l’arte a Siena al tempo di Pandolfo Petrucci. Annali di studi umanistici 5 (2017). The exact number and dates of Beccafumi’s sojourns in Rome are uncertain, see Nicole Dacos, “Beccafumi e Roma,” in Agosti (note 1), pp. 44–59; Ginzburg (note 1). ↩︎

-

On the city of Siena, its art, and artists in the Renaissance period, see Keith Christiansen, Laurence B. Kanter, Carl Brandon Strehlke, eds. Painting in Renaissance Siena: 1420–1500, (New York: Abrams in Komm., 1988); Lawrence Jenkens, ed. Renaissance Siena: Art in context (Kirksville: Truman State University Press, 2005); Luciano Bellosi, ed. Francesco di Giorgio e il Rinascimento a Siena 1450–1500 (Milan: Electa, 1993); Luke Syson, ed. Renaissance Siena: Art for a City, exh. cat. (London, National Gallery, 2007); Fabrizio Nevola, Siena: Constructing the Renaissance City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007). ↩︎

-

Fiorella Sricchia Santoro, “La vita,” in Agosti (note 1), p. 60. ↩︎

-

Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, Gaston C. de Vere, ed. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1912–1915), vol. 6, p. 248. On the relationship between Vasari and Beccafumi, see Barbara Agosti, “Sulla costruzione della Vita vasariana di Beccafumi,” Annali di studi umanistici 5 (2017), pp. 23–36. ↩︎

-

For an overview of Catherine’s figure, her writings, and later cult, see Carolyn Muessig, George Ferzoco, and Beverly Kienzle, eds. A Companion to Catherine of Siena (Leiden, Brill: 2012). ↩︎

-

Catherine’s conversations with God on theological matters are narrated in her writing Il dialogo della divina Provvidenza ovvero Libro della divina dottrina, Giuliana Cavallini, ed. (Rome: Edizioni cateriniane, 1980). ↩︎

-

The central role played by Catherine in international matters is documented by her extant epistolary, the largest left by a woman by that time, which consists of more than 300 letters addressed to eminent contemporary figures, including kings, queens, and popes, see The Letters of Saint Catherine of Siena, Eng. trans. ed. Suzanne Noffke (Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2000–2008). ↩︎

-

Raymond’s account combines his own memories with the testimonies of Catherine’s disciples and family, including her mother Lapa, see Raymond of Capua, Legenda maior sanctae Catharinae Senensis (Florence: San Jacopo di Ripoli, 1477), Eng. trans. The Life of St. Catherine of Siena (Charlotte, North Carolina: TAN Books, 2011). ↩︎

-

Raymond of Capua (note 9), pp. 347–350. The representation (or invisibility) of Catherine’s stigmata and the divine rays piercing her body engendered a theological controversy that divided the Franciscan and Dominican Orders until the seventeenth century, see Diega Giunta, “The Iconography of Catherine of Siena’s Stigmata,” in Muessig, Ferzoco, and Kienzle (note 6), pp. 259–294. ↩︎

-

Raymond of Capua (note 9), pp. 579–589. ↩︎

-

On the early cult around Catherine and the circulation of her first devotional images, see Diega Giunta, “L’immagine di S. Caterina da Siena dagli ultimi decenni del Trecento ai nostri giorni,” in Iconografia di S. Caterina da Siena, Lidia Bianchi and Diega Giunta, eds. (Rome: Città Nuova, 1988), especially pp. 65–88; Muessig, Ferzoco, and Kienzle (note 6). ↩︎

-

The panels originally formed a predella that was probably added to the preexisting altarpiece of the guild of the Pizzicaiuoli (purveyors of dry goods) in Santa Maria della Scala. On the dating and commission of the panels, see Carl Brandon Strehlke “The Saint Catherine of Siena Series,” in Christiansen, Kanter, and Strehlke (note 3), pp. 218–242, cat. 38a–m; Keith Christiansen, “Giovanni di Paolo, The Miraculous Communion of Saint Catherine of Siena,” online catalogue entry, 2012, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436511 (accessed August 21, 2021). ↩︎

-

Another panel, probably from the same predella by Girolamo di Benvenuto, is in the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard Art University (inv. 1947.25); see Angelica Daneo, The Kress Collection at the Denver Art Museum (Denver: Denver Art Museum, 2011), pp. 126–131. ↩︎

-

See for instance, Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Nativity with Saint Bernard and Thomas Aquinas, c. 1475, Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena, inv. 437. The painted altarpiece in the background of the Getty Stigmata also recalls the Nativities completed by Beccafumi himself around the same years, including The Adoration of Christ, c. 1513–1514, Pesaro, Musei Civici. On the painted altarpiece, see also Exhibition of the Marshall Collection [.…], exh. cat. (London: Sotheby & Co., 1973), p. 45, cat. 62; Torriti (note 1), p. 75; Pascale Dubus, Domenico Beccafumi (Paris: Adam Biro, 1999), p. 64. ↩︎

-

Torriti (note 1), p. 75. For Vecchietta’s ciborium, see Andres Pfeiffer, Das Ciborium im Sieneser Dom: Untersuchungen zur Bronzeplastik Vecchiettas, Ph.D. dissertation (Philipps-Universität Marburg, Marburg: 1975); and more recently, Giulio Dalvit, Rethinking Lorenzo di Pietro, Known as Vecchietta (Siena, 1410–80), Ph.D. dissertation (The Courtauld Institute of Art, London: 2020), notably pp. 175–210. ↩︎

-

See the reports of the infrared reflectography and X-radiography examinations carried out on the panels in 1997 following their acquisition by the Getty (Paintings Conservation Department file). A special thank you to conservator Devi Ormond and Michelle Tenggara for sharing their expertise and insights about the paintings with me. ↩︎

-

Vasari (note 5), vol. 6, p. 237. Luigi Lanzi, The History of Painting in Italy (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1847), vol. 1, p. 298. On Beccafumi’s predella panels, see also Donato Sanminiatelli, “Domenico Beccafumi’s Predella Panels,” Le Connoisseur 38 (1956), pp. 155–159. ↩︎

-

See for instance The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena, c. 1528, Siena, Chigi-Saracini Collection, property of Monte dei Paschi di Siena, inv. 277; the detached fresco featuring the Stigmatization of Saint Catherine (c. 1513, Palazzo Chigi Saracini) and the painting of an identical subject (c. 1540, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen Rotterdam, inv. 2898) attributed to Beccafumi, see respectively Torriti (note 1); pp. 129–130, cat. P52; pp. 67–69, cat. P8; Syson (note 3), pp. 311–313, cat. 97. ↩︎

-

Torriti (note 1), pp. 70–74, cat. P11. ↩︎

-

The composition of Beccafumi’s Stigmatization closely resembles the altarpiece by Fra Bartolomeo (1472–1517), Saint Catherine, Mary Magdalen and God the Father, c. 1509, Lucca, Museo Nazionale di Villa Guinigi. Beccafumi probably saw Fra Bartolomeo’s painting during a visit to Florence, before the work was taken to Lucca, see Claudio Gulli, “Il vasto raggio di Fra Bartolomeo,” in Alessi (note 2), pp. 79–84; Ginzburg (note 1), p. 161. ↩︎

-

Michele Maccherini in Agosti (note 1), p. 110. ↩︎

-

On the paintings’ dating and attribution, see Torriti (note 1), p. 75; Roberto Bartalini in Agosti (note 1), p. 98, cat. 4. Most recently, Andrea De Marchi convincingly suggested that the panels should be dated right before 1513, see “La prospettiva sconvolta: Beccafumi verso il tornante del 1513,” in Alessi (note 2), p. 91. ↩︎

-

Bartalini suggested a stylistic comparison between the Getty panels and the work of the Spanish painter Pedro Fernández (c. 1480–after 1521), who was active in Rome at the time of Beccafumi’s visit, see Bartalini in Agosti (note 1), p. 98, cat. 4. ↩︎

-

The Mystic Marriage, c. 1528 (oil on panel, 310 x 230 cm); Virgin and Child with Saints, c. 1535–1537 (oil on panel, 315 x 285 cm), Siena, Oratory of San Bernardino da Siena. For the altarpieces, see, respectively, Torriti (note 1), pp. 129–130, cat. P52; pp. 145–147, P67–68a–g. ↩︎

-

The order of the predella panels is reversed in the current modern frame. Originally, the predella featured, from left to right, the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, the Miraculous Communion, and Saint Catherine receiving the Lily and the Dominican Habit, see Michele Maccherini in Agosti (note 1), p. 110. ↩︎

-

Nativity of the Virgin, c. 1530 (oil on panel, 225 x 145 cm), Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Torriti (note 1), pp. 149–151, cat. 70. ↩︎

-

Vasari (note 5), vol. 6, pp. 235–251. See also the altarpieces and panels mentioned by Giovanni Antonio Pecci, Relazione delle cose più notabili della città di Siena sì antiche come moderne (Siena: Quinza & Bindi, 1752), pp. 124, 133–134. ↩︎

-

Among the few altarpieces by Beccafumi still in loco are the Nativity in the church of San Martino (c. 1522) and Saint Michael and the Rebel Angels (missing its original predella) in San Niccolò al Carmine (c. 1535). Panels from Beccafumi’s major altarpieces are today found primarily in Siena at the Pinacoteca Nazionale and the Chigi Saracini Collection. ↩︎