One of only two paintings by Marco Pino in the United States, Christ on the Cross with the Virgin, Saint John the Evangelist, and Saint Catherine of Siena in Adoration offers a rare opportunity to appreciate the work of this refined and original protagonist of the Italian Cinquecento.

Marco Pino paints a solemn and dramatic scene. Against a gloomy sky, the lifeless body of Christ hangs from a slender wood cross, his head slumped and surmounted by a feeble ray of light, his hands and feet pierced by iron nails. The elegant and monumental figure of the Virgin (left) looks up at the Christ while Saint John (right) gazes directly at the viewer. From the bottom right, Saint Catherine of Siena witnesses the scene. Catherine is dressed in the robes of the Dominican Order, hands folded in prayer holding a lily and a small cross, and eyes cast towards the Crucifixion group. The chromatic contrasts of Pino’s vivid palette enhance the dramatic moment of Christ’s expiry and encapsulate the expressive quality and emotional charge of the painting.

Like many artists of his generation, Pino led an itinerant life, which distinctively enriched his style and works.1 Born in Siena in 1521, he trained in the studio of Domenico Beccafumi (1484–1551) before moving to Rome in the early 1540s “to try his fortune”, as recalled by the art collector and writer Giulio Mancini (1559–1630).2 After ten years of intense work in the capital, Pino relocated to Naples, where he opened a prolific studio and quickly became one of the leading painters of the city, achieving local and international fame. Before permanently settling in Naples, the artist made a final trip to Rome (1568–1570), during which he likely painted the Getty’s Christ on the Cross.3

The years spent in the flourishing Roman artistic scene gave Pino the opportunity to collaborate with the most famous artists of the day, including Perino del Vaga (1501–1547) and Daniele da Volterra (1509–1566), as well as closely study the works of great masters such as Raphael (1483–1520) and, most notably, Michelangelo (1475–1564). According to later sources, Pino developed a close and friendly relationship with Michelangelo.4 The painter and writer Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo (1538–1600), who personally knew Pino, recalled that Michelangelo advised the younger artist on painting practices:

“one should always make the figure pyramidal, serpentine, and multiplied by one, two or three. And in this precept, it seems to me, is contained the secret of painting, for the figure has its highest grace and eloquence when it is seen in movement – what the painters call the Furia della figura. And to represent it thus there is no better form than that of a flame, because it is the most mobile of all forms and is conical. If a figure has this form it will be very beautiful.”5

Pino carefully interpreted the guidance given by the older master. Serpentine and pyramidal figures populate his major works, including the Pietà painted for the Basilica of Santa Maria in Aracoeli in Rome (c. 1571), the Resurrection today at the Galleria Borghese (1568–1570), and Christ on the Cross. In the Getty panel, the twisted poses of the Virgin and Christ’s bodies confer dynamism to the otherwise symmetrical composition, thereby meeting the canons of beauty set by Michelangelo’s recommendations.

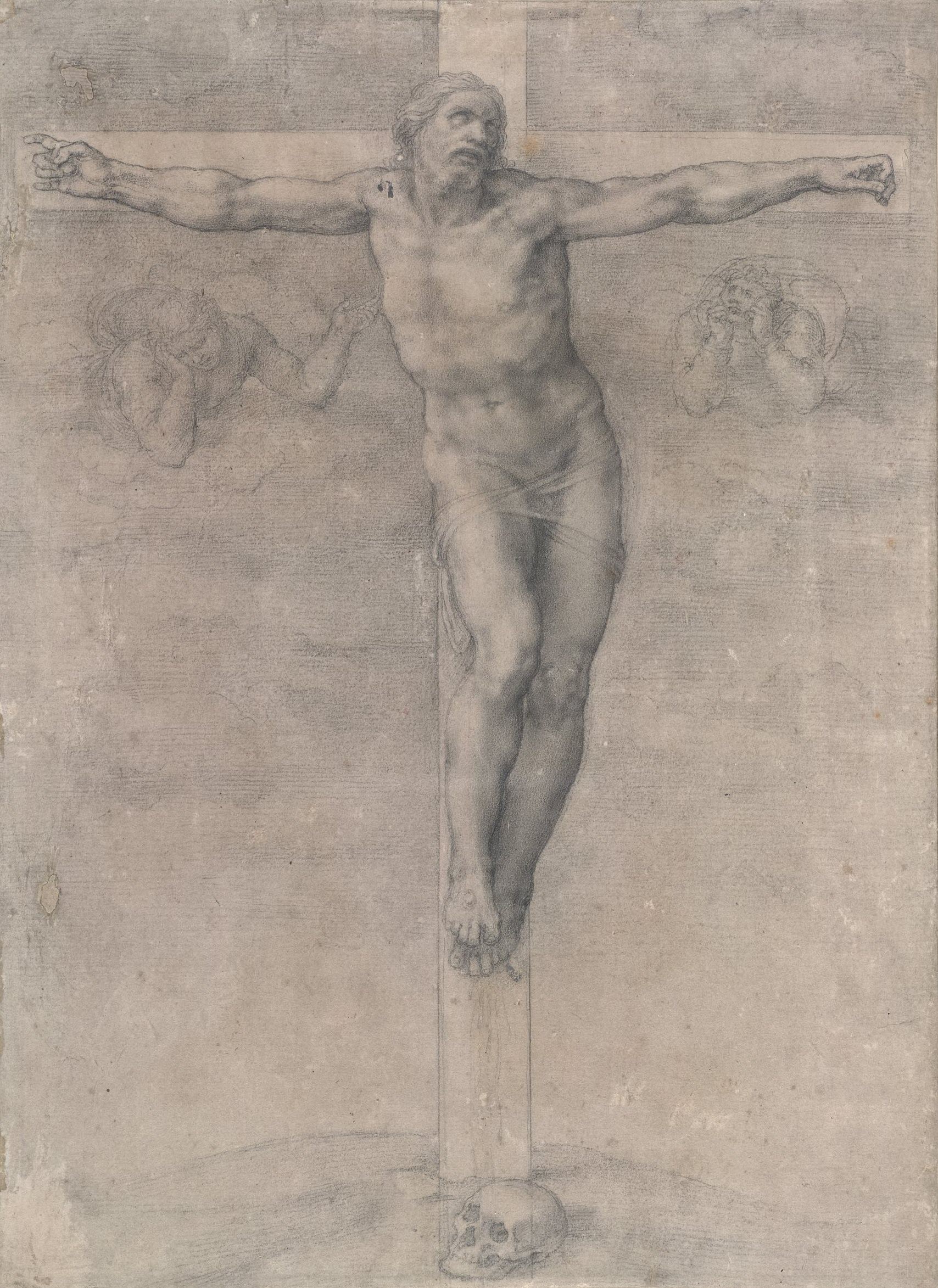

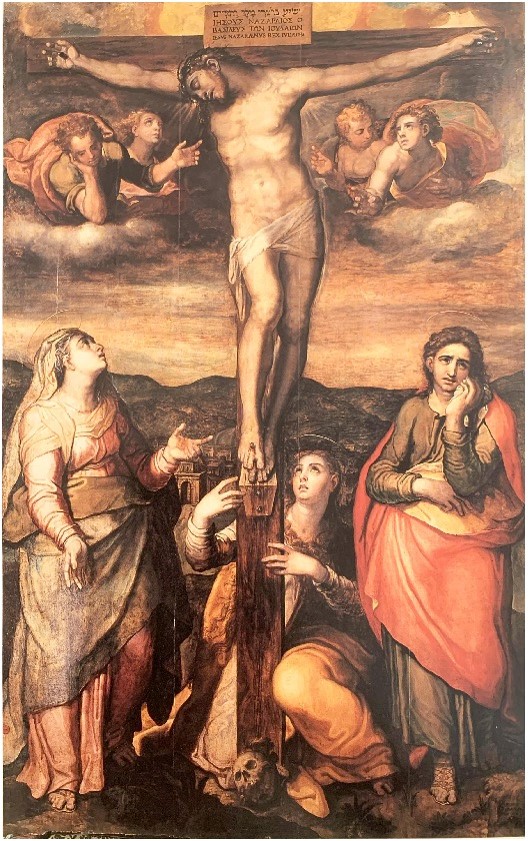

Michelangelo explored the subject of the Crucifixion in several drawings made over the years, the most famous of which is the sheet given to his friend, the poetess and marchioness of Pescara, Vittoria Colonna (1490–1547) (fig. 1).6 Michelangelo’s Crucifixion drawings enjoyed great fame and his rendering of the theme was copied and developed by many contemporary artists, including Giulio Clovio (1498–1578), Marcello Venusti (1512/1515–1579), and Marco Pino himself.7 Stimulated by this illustrious example, Pino painted several variations of the Crucifixion in the 1570s, including those for the Neapolitan churches of Santi Severino e Sossio (1571), Santa Maria del Popolo agli Incurabili (1577), and San Giacomo degli Spagnoli (1571) (fig. 2), which bears strong similarities with the Getty painting. Quoting but not copying, Pino cleverly reinterprets Michelangelo’s composition in the latter, maintaining the monumental cross truncated at the top, as well as the twisted pose of the vigorous body of Christ. However, unlike Michelangelo who depicted Christ alive, his idealized body untouched by suffering,8 Pino chose to represent the more tragic image of the death of Christ, hence introducing a powerful contrast between his collapsed head, falling lock of hair and open mouth, and the tension of his contorted muscular body.9

In addition to Michelangelo’s example, Pino’s painting is enriched by other artistic stimuli encountered during his travels. In Naples, Pino had most certainly seen the Crucifixion (1545) completed by Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) for the chapel of the eminent cardinal Girolamo Seripando (1493–1563) in the church of San Giovanni a Carbonara (fig. 3):10 the cartouche crowning the cross, ominous pink sky, hilly landscape inhabited by figurines, and antique architectural elements of Vasari’s altarpiece all closely resemble those painted by Pino some years later.

However, the Getty painting is uniquely distinguished from the Crucifixions of Michelangelo, Vasari, and indeed other Crucifixions by Pino himself, by a striking feature: the presence of Saint Catherine in the foreground. Catherine (1347–1380), like Pino, was Sienese: born to a modest family, the Beninacasa, she became a Dominican tertiary (a lay member of the Order) in the 1360s, when she was about sixteen. Throughout her life, Catherine claimed to have experienced numerous apparitions and miraculous events that physically manifested her extraordinary spiritual faith, including levitation, ecstasy, and, most significantly, stigmata. According to the biography written by her confessor and disciple, Raymond of Capua (1330–1399), while in Pisa on a Sunday, Catherine had a vision of the Christ on the Cross from whose wounds came rays of blood that pierced the body of the blessed, leaving invisible stigmata.11 In the Getty panel, Pino has carefully included the holy wounds, which are faintly visible on the Saint’s joined hands. The painting evokes this episode of Catherine’s life and combines it with the biblical narrative of the Crucifixion, thereby merging chronologically distant figures and events into a single scene. Present in the picture, yet detached from the narrative, Saint Catherine is both the protagonist and a witness to the event – both subject and object of contemplation. The presence of Catherine enriches and complicates the iconography of Pino’s Crucifixion, making it a highly unusual and original example of this traditional subject.

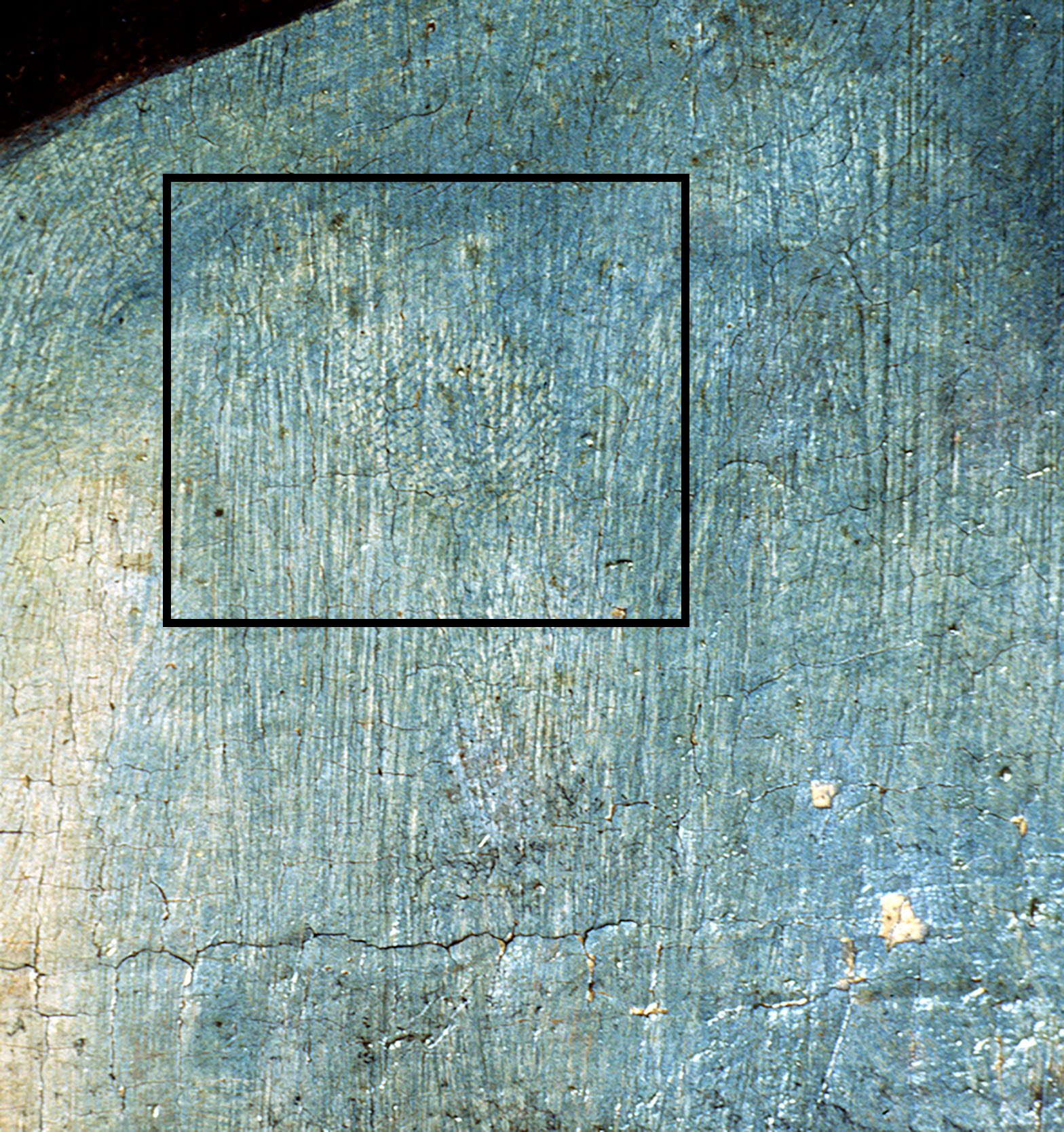

The contemplative and expressive character that distinguishes Pino’s painting and unites it with Vasari and Michelangelo’s Crucifixions was meant to address specific needs dictated by the religious climate in which the artist operated. The decades around the mid- and late sixteenth century were defined by the Counter-Reformation, the process of self-review and renewal of the Catholic Church in response to the denunciations made by the Protestant Reformation. Such moral and religious change gradually impacted the visual arts, and most notably, its devotional function. New devotional images, like those painted by Pino, were intended to provoke an interior response in the viewer, encouraging contemplation and inspiring piety and worshipful sentiments.12 Scenes depicting the Passion of Christ, including the Crucifixion, were particularly suited to this contemplative function. Pino’s work complied with these requirements, while also maintaining a high degree of inventiveness and expressive freedom: the artist proved able to produce images that were both easily readable and powerfully engaging. The Getty panel is a fine example of Pino’s ability to achieve such an iconic yet expressive effect, which he obtained by balancing a simple and structured composition with a contrastingly emotive color palette and moving details, like the theatrical features of the Christ’s body or the restless sky.13 To create this vivid atmospheric background, Pino first applied a bright orange-red underlayer (imprimatura), followed by a pink layer, which was intended to be visible in the background and bestows a sense of transcendence to the scene. Pino further rendered the texture of the sky by energetically applying the paint, which he later modelled using his fingers.14 Five centuries later, the Getty painting still, quite uniquely, preserves the fingerprint of the artist (fig. 4).

To further enhance the engaging power of his image, Pino directly involved viewers in the scene. The artist seems to have deeply considered how to engender this interactive experience while developing the Getty painting and made changes to its composition accordingly: infrared examination conducted on the panel reveals that the figure of Saint John did not originally face the viewer, but looked at the crucified Christ in a pose similar to that of the Virgin.15 By switching the direction of John’s gaze and his stance, Pino infused the scene with a more dynamic quality and expanded the compositional space so as to involve the beholder. This effect is further enhanced by the Virgin’s gesture of extending her hand and, most notably, by the presence of Saint Catherine in the foreground. The Saint acts as an intermediary between the earthly observer and the holy figures, guiding the viewers into the Crucifixion scene. Half-length foreground figures, such as Catherine, feature frequently in Pino’s paintings of this period,16 and were also adopted by some of his contemporaries, including Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572) and Daniele da Volterra. Their presence allows paintings to engage with the beholder and was often used to include patrons and donors in the composition. This is the case, for instance, with the Christ on the Cross (1566–1568) painted by Orazio Samacchini (1532–1577) in Santa Maria dei Servi in Bologna (fig. 5). The altarpiece presents a remarkably similar composition to that of the Getty panel, and portrays the donor, the Bolognese senator Ulisse Gozzadini (1505–1561), in place of Saint Catherine. The representation of Catherine in the position often reserved for patrons and her relevant role within the picture might serve as evidence to trace the provenance of Christ on the Cross.

While nothing is known of the original location of the panel, its devotional subject and large size indicate that it initially functioned as an altarpiece, which was possibly intended for a chapel or a monastic interior.17 In the 1570s, the years in which Pino produced Christ on the Cross, many female monasteries were being reformed in Rome in the surge of the Tridentine legislation. Among the regulations promulgated by the Council of Trent, the decree De regularibus et monialibus (Session xxv, chapter 5, 3–4 December 1563) re-enforced the seclusion of female religious communities and led to the development in the following years, in Rome as in other cities, of new cloistered establishments.18 In particular, in the Rione of Monti in Rome, the Dominican nuns founded several new monasteries between the 1560s and 1570s, including those of the Santissima Annunziata delle neofite and Santa Caterina da Siena a Magnanapoli.19 Dominican communities, such as those of the Annunziata and Santa Caterina were supported by and comprised of noblewomen, daughters, and widows from the highest-ranking classes of society. Although segregated from the secular world, some of these women were active art patrons and, through the intermediation of families and external agents, were able to commission significant artworks.20 As the focus on Catherine’s figure (a Dominican Saint), seems to suggest, Pino’s Christ on the Cross could have been painted for one of these cloistered Dominican communities, where it would have remained unseen by writers and biographers for decades. The size of the altarpiece, less monumental than those painted by Pino in those same years for high altars or prominent private chapels, would be consistent with this more secluded location. Further connections to this monastic, and notably Roman Dominican, context may be suggested by the painting itself: the background landscape of the Getty panel includes specific allusions to Roman scenery, such as the Tiber river, Trajan’s Market (at the right of Christ’s feet) and, notably, the Milizie and Conti towers (at the left) (fig. 6). The old medieval towers stood in the Rione of Monti where the Dominicans established their new monasteries and, in the late sixteenth century, the Milizie tower was incorporated in the complex of Santa Caterina a Magnanapoli. It cannot be excluded that these topographical references in Pino’s painting might allude to a direct involvement of the Roman Dominicans in the commission of the painting.

The devotional subject, engaging power, and emotional charge of Christ on the Cross were perfectly suited to the needs of the religious communities that developed in the last decades of the sixteenth century. The painting, prominently featuring Saint Catherine of Siena, reflected the widespread cult around this figure that involved several monasteries, notably Dominican, reformed in those years. Concurrently, the moving character of the altarpiece responded to the new normative standards that the Counter Reformation introduced in the visual arts at that time. Marco Pino achieved this synthesis with great inventiveness, creating a stylistically sophisticated painting that seamlessly merged the specific demands of the patrons, the religious sentiment of the period and the latest artistic trends.

- Saida Bondini

-

The first comprehensive study of Marco Pino’s life, style, and career was given by Evelina Borea, “Grazia e Furia in Marco Pino,” Paragone 13 (1962), pp. 24–52. For a more recent analysis of Pino’s work, see Pierluigi de Castris, “Le presenze forestiere. Marco Pino,” in Pittura del Cinquecento a Napoli: 1540–1573. Fasto e devozione (Naples: Electa Napoli, 1996), pp. 185–232; and notably Andrea Zezza, Marco Pino: l’opera completa (Naples: Electa Napoli, 2003). ↩︎

-

“Tentò sua fortuna in Roma” Giulio Mancini, Considerazioni sulla pittura (Rome, 1620), Adriana Marucchi, ed. (Rome: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 1956), vol. 1, p. 198. ↩︎

-

For the dating of the Getty panel, see Zezza 2003 (note 1), p. 263, cat. A 17. ↩︎

-

The relationship between Pino and Michelangelo is mentioned by the Dutch biographer Karel van Mander. Het Schilder-Boeck (Haarlem, 1603–1604), fol. 195r; Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, Trattato dell’arte della pittura, scoltura et architettura (Milan: Gottardo Ponzio, 1584), Roberto Paolo Ciardi, ed. in Scritti sulle arti, vol. 2 (Florence: Centro Di, 1974), pp. 29–30; and Mancini 1620 (note 2), vol. 1, pp. 197–198; on Pino’s contacts in Rome, see also Giovanni Baglione, Le vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti (Rome, 1642), Jacob Hess and Herwart Röttgen, eds. (Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1995); Bernardo De Dominici, Vite de’ Pittori, scultori e architetti napoletani (Naples, 1742–1745), eds. Fiorella Sricchia Santoro and Andrea Zezza (Naples: Paparo, 2003–2010). ↩︎

-

Lomazzo (note 4), pp. 29–30. On the meeting of Pino and Lomazzo, see Zezza 2003 (note 1), pp. 76, 83. On the serpentine figure discussed by Michelangelo, see David Summers, “Maniera and Movement: the Figura Serpentinata,” The Art Quarterly 35 (1972), pp. 265–301. ↩︎

-

On Michelangelo’s Christ on the Cross for Vittoria Colonna and his other drawings of the Crucifixion, see Michael Hirst, Michelangelo and His Drawings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), pp. 117–118; Michael Hirst, “Michelangelo, Pontormo e Vittoria Colonna,” Tre saggi su Michelangelo (Florence: Mandragora, 2004), pp. 4–29; Pina Ragioneri, ed. Vittoria Colonna e Michelangelo, exh. cat. (Florence, Casa Buonarroti, 2005), pp. 165–167, cat. 49; Carmen Bambach, Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman & Designer, exh. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017), notably, pp. 194–199, 222–231. ↩︎

-

Later copies and reworkings of this subject often combine Michelangelo’s Crucifixion with other drawings by the artist, such as those depicting the Virgin and Saint John (Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts Graphiques [inv. 698 and inv. 720]; Royal Collection Trust/ Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II [inv. 912761 recto]). ↩︎

-

The iconography of Christ alive on the Cross, the so-called Cristo vivo, quickly became popular and inspired the work of numerous sixteenth- and seventeenth-century artists, including Marco Pino. See, for example, the large Crucifixion for the church of Santi Severino e Sossio in Naples (1571); the drawing with Christ on the Cross with Saint John and the Holy Women below, c. 1577 (London, British Museum, inv. 1856,0712.3). On the iconography of the living Christ, see Francesco Negri Arnoldi, “Origine e diffusione del Crocefisso barocco con l’immagine del Cristo vivente,” Storia dell’arte 20 (1974), pp. 57–79; on its use by Pino, see Francesca Parrilla, “Marco Pino. ‘Cristo vivo sulla croce’,” Quaderni del Barocco 37 (2019), pp. 1–16. ↩︎

-

Zezza 2003 (note 1), p. 194. ↩︎

-

For Vasari’s painting, see Riccardo Naldi, “Il crocifisso per Girolamo Seripando e il suo contesto,” in Marco Cardisco, Giorgio Vasari, Riccardo Naldi, ed. (Naples: Quaderni del Dipartimento di Filosofia e Politica, 2009), pp. 106–135. ↩︎

-

“I saw the Lord fixed to the cross coming towards me in a great light, and such was the impulse of my soul to go and meet its Creator that it forced the body to rise up. Then from the scars of His most sacred wounds I saw five rays of blood coming down towards me, to my hands, my feet and my heart,” Raymond of Capua, Legenda maior sanctae Catharinae Senensis (Florence: San Jacopo di Ripoli, 1477), Eng. trans. The Life of St. Catherine of Siena, Conleth Kearns ed. (Wilmington: Glazier, 1980), see in particular pp. 185–187. ↩︎

-

For the related decrees of the Council Trent, see Henry J. Schroeder, ed. Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent (Rockford: Tan, 1978); on the role and value of images in the Counter-Reformation years see also the discourse by Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, Discorso intorno alle immagini sacre e profane (Bologna, 1582) (Città del Vaticano: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2002). ↩︎

-

Interestingly, the scholar Federico Zeri, who first published Christ on the Cross in 1957, provided a critical view of the painting, arguing that it encapsulated a tendency towards “mystic irrationality” in the visual arts, which manifested during the Counter-Reformation period, see Federico Zeri, Pittura e controriforma: L’arte senza tempo di Scipione da Gaeta (Turin: Einaudi, 1957), pp. 39–40. ↩︎

-

Elma O’Donohue, Treatment report (December 31, 1997), Department of Paintings Conservation, The J. Paul Getty Museum, p. 2. ↩︎

-

Elma O’Donohue, Treatment report (December 31, 1997), Department of Paintings Conservation, The J. Paul Getty Museum, p. 3. ↩︎

-

Half-length figures in the foreground are present in the large panels painted by Pino in the 1560s, such as The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, early 1560s (oil on panel, 190 x 140 cm [74 13/16 x 55 1/8 in.]), Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, inv. SG. 1852; The Circumcision of Jesus, 1566–1569 (oil on panel, 484 x 338 cm [190 1/2 x 133 1/16 in.]), Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, inv. S. 84177; and the Baptism of Christ, 1566–1569 (oil on panel, 465 x 306 cm [183 1/16 x 120 5/32 in.]), Naples, Church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, see Zezza 2003 (note 1), p. 275, cat. A.59; pp. 272–273, cat. A.56; p. 268, cat. A.38 respectively. ↩︎

-

The Getty panel is not recorded in the known biographies and sources relating to Marco Pino (see note 4 above and subsequent references). The painting emerged on the British market during the nineteenth century and eventually entered the United States in the 1950s. ↩︎

-

For the Tridentine regulations on female seclusion, see Schroeder 1978 (note 12), pp. 220–221; Alessia Lirosi, I monasteri femminili a Roma tra XVI e XVII secolo (Rome: Viella, 2013). ↩︎

-

Mario Bevilacqua, Santa Caterina da Siena a Magnanapoli. Arte e storia di una comunità religiosa romana nell’età della Controriforma (Rome: Gangemi, 2009); Lirosi (note 18). ↩︎

-

On the artistic patronage of female communities in Italy and Rome specifically, see Marilyn Dunn, “Nuns, Agents and Agency: Art Patronage in the Post-Tridentine Convent,” in Patronage, Gender and the Arts in Early Modern Italy, Katherine A. McIver and Cynthia Stollhans, eds. (New York: Italica Press, 2015), pp. 127–151; Marilyn Dunn, Saundra Lynn Weddle, eds. Convent Networks in Early Modern Italy (Turnhout: Brepols, 2020). ↩︎