In 1953, Edward Weston’s son Brett (1911-2003) and Brett’s wife, Dody Warren Weston (1923-2012), first suggested in a letter to writer and friend Nancy Newhall (1908-1974) and her husband, photo historian Beaumont Newhall (1908-1993), the idea of creating a book of Weston’s nude figure studies. Suffering from advanced Parkinson’s disease, Weston had stopped photographing in 1948. Generating income from his large existing body of work was of particular interest to Weston and those concerned with his well-being, but the motivation for preparing a book on Weston’s nudes, a favorite subject throughout his career, went far beyond the financial. The subject of the nude had been significantly underrepresented in publications on the artist up to that point; a book dedicated to this subject was surely intended to address this imbalance.

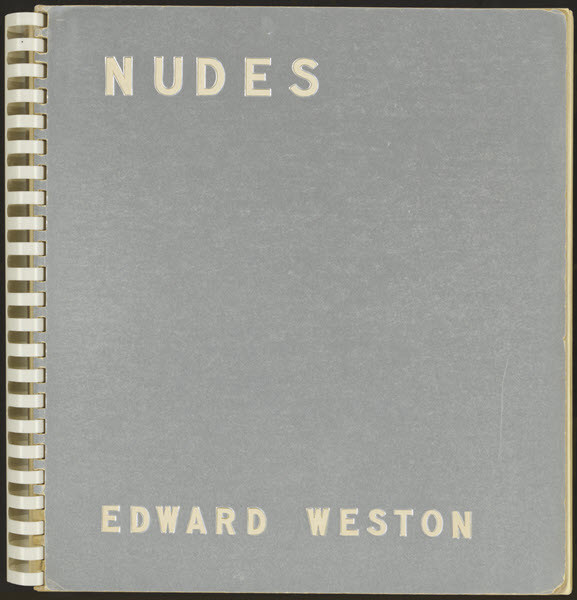

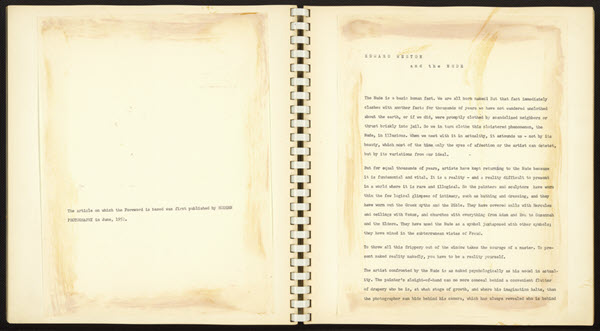

Nancy Newhall, who had recently published an article in Modern Photography about Weston’s nudes, took the lead on the project, enclosing a small number of Weston’s photographs in a letter written to Charles Duell of Duell, Sloan & Pearce,the publishing company that had produced three of Weston’s previous books. Thinking it would be better to show a larger representation of his work to potential publishers, Weston forwarded to Newhall fifty-two prints of nudes along with some still lifes and landscapes that would resonate with the nudes. Newhall chose thirty-nine of the fifty-two images that she laid out in sequence in a spiral bound maquette (fig. 1) that included a revised, augmented version of her article (fig. 2).

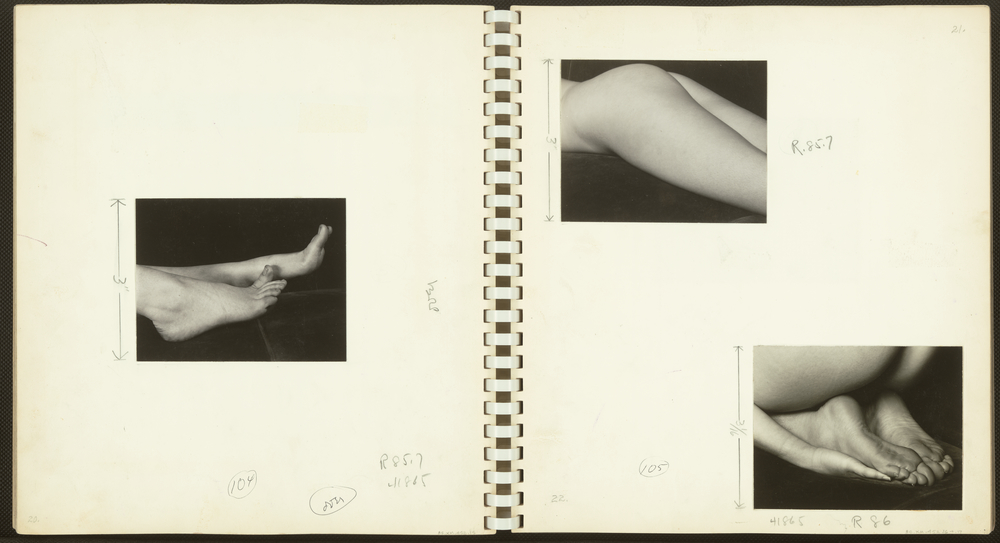

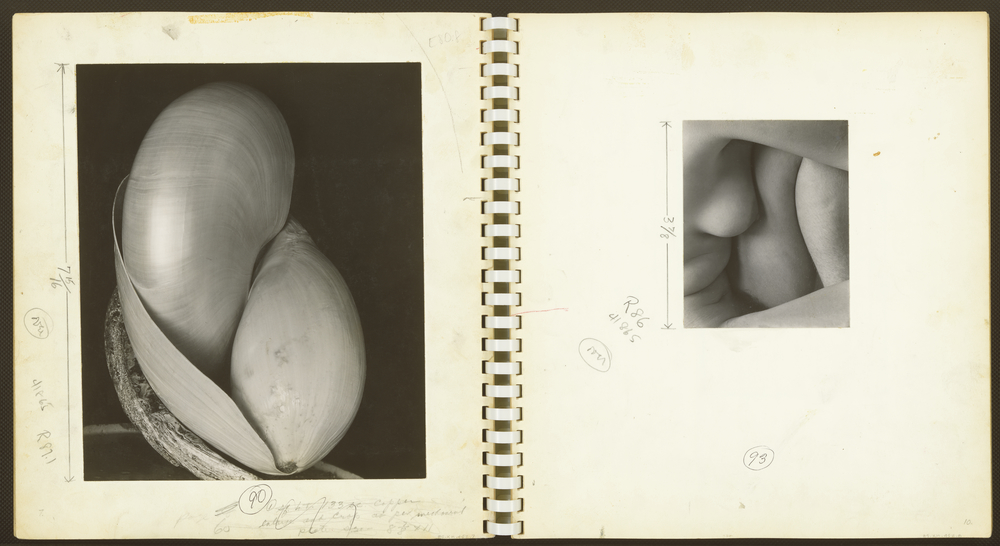

The photographs, most likely printed by Brett, unfold roughly chronologically, but do not show the full breadth of Edward’s exploration of the nude; the earliest photograph dates from 1925. Newhall did not center the prints on the page, but rather thoughtfully used negative space and asymmetrical placements to heighten the visual interest of the presentation (fig. 3). Her interspersal of the non-nude subjects—shells, a pepper, kelp, and dunes—demonstrated the artist’s unifying vision of natural forms (fig. 4).

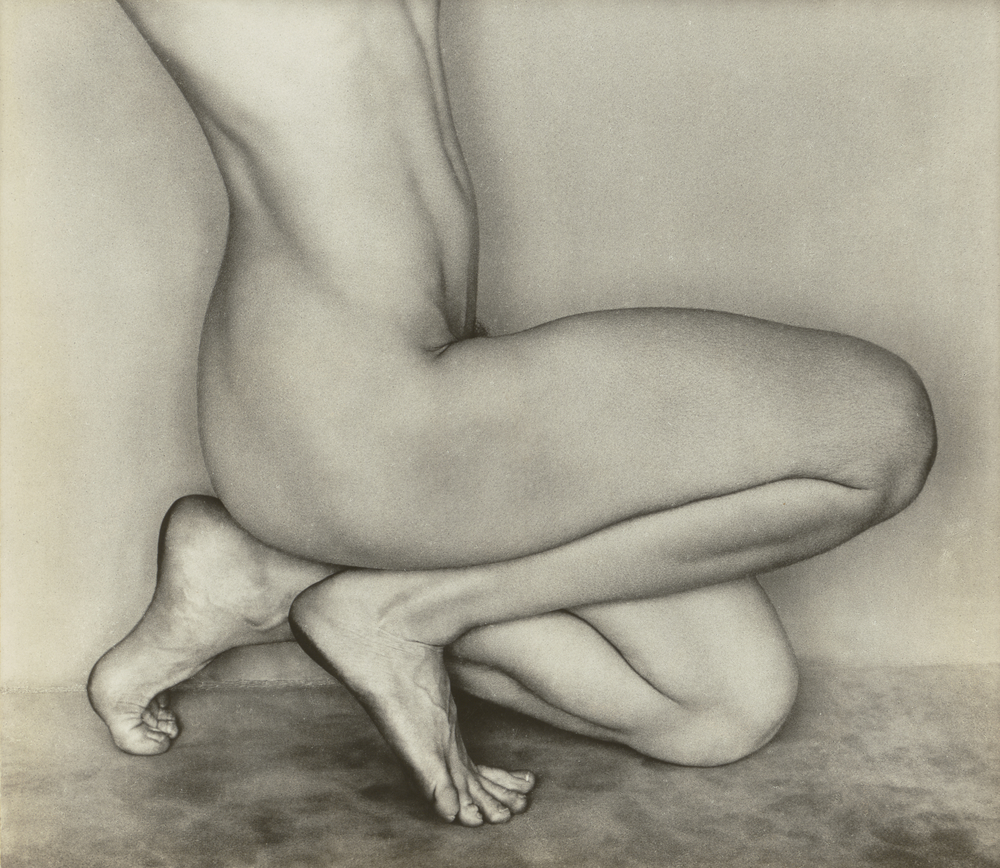

Art historian Jessica Todd Smith notes that, “Although Weston resisted making Freudian connections between human and inanimate forms, in his journal he emotionally described the revelation he felt while making the photographs of Bertha Wardell, the model for Knees of a Dancer (fig. 5).”1

Questions of propriety may have been what steered publishers away from the project. Duell and other publishers were reluctant to publish such a book, which they said had a very small market. The full sequence was eventually printed in a cheaply produced paperback volume in 1957 by Maco Magazine Corporation, without captions or the Newhall essay, but paired with sixty-two nudes by fashion photographer John Rawlings. Thus, Weston’s concept for an exquisite presentation met an undignified end, at least in his lifetime. It was not until 2007 that his and Newhall’s vision was fully realized in print in a publication by the J. Paul Getty Museum. View other pages in the album (85.XM.452.1-.26).

Adapted from Brett Abbott. “Edward Weston’s Book of Nudes: The Path to Publication.” In Edward Weston’s Book of Nudes, Brett Abbott (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007). © 2007, J. Paul Getty Trust; with additions by Carolyn Peter, Department of Photographs, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019.

-

Jessica Todd Smith, “Time of Exposure: Nancy Newhall’s Unpublished Book of Edward Weston’s Nudes,” in Edward Weston: A Legacy, edited by Jennifer A. Watts, 83-101, (London: Merrell Publishers, Ltd., in association with The Huntington Library, 2003), 94 ↩︎

-

Edward Weston, The Daybooks of Edward Weston, vol. 2: California, ed. Nancy Newhall, New York (The Horizon Press in collaboration with the George Eastman House, Rochester) 1961-66, p. 10. ↩︎

-

Todd Smith, 96. ↩︎