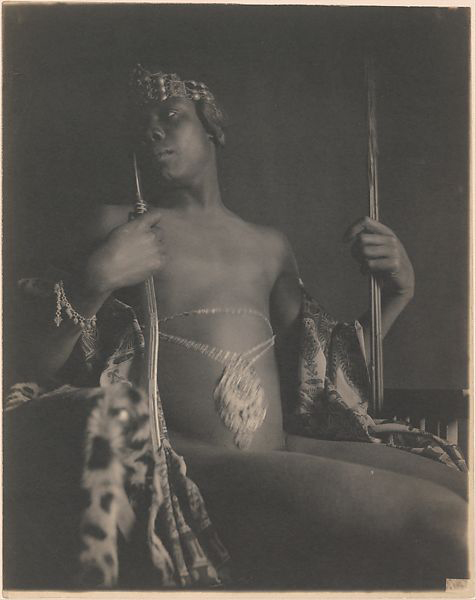

In the late 1890s Fred Holland Day (known as F. Holland Day) created a group of photographs featuring the Black artist and model J. Alexandre Skeete, who dressed in costumes, wore elaborate accessories, and held props that evoked Day’s image of African royalty. In this picture, Skeete poses as an Ethiopian chief, partially clothed in a draped robe and feather headdress. He holds a spear; a metal orb is located near his right hip; he casts his gaze downward, appearing self-possessed and strong.

By applying titles such as Ethiopian Chief, Nubia, and Menelek to these photographs, Day imagined both an Africa of his day and of the ancient past. The Getty’s photograph alludes to a generalized idea of an Ethiopian leader. However, another image of Skeete—Menelek (fig-1)—references two specific Ethiopian emperors. In 1896, just one year before Day began his series, Emperor Menelik II (1844-1913) had defeated Italian invaders at Adwa in Northern Ethiopia. Upon the Italians’ retreat, the two countries agreed to the Treaty of Addis Ababa that recognized the full independence of Ethiopia. Emperor Menelik II chose his name to honor his ancestor, the 10th-century BC Emperor Menelik I who had founded the Kingdom of Abyssinia (later Ethiopia). Menelik I was the son of Makeda, Queen of Sheba, and King Solomon. He is said to have taken the Ark of the Covenant, which contained the Ten Commandments, from Jerusalem to Ethiopia, where he introduced Christianity to the Ethiopians.1

Skeete was born January 16, 1874, in British Guiana and immigrated to the United States in 1888 to pursue career in art. He attended Cowles Art School in Boston and graduated with honors. He worked as an illustrator for the Boston Herald and as an art editor and illustrator for the Colored American Magazine. It is not known when Skeete met Day, but he posed for at least ten of Day’s photographs between 1897 and 1899.

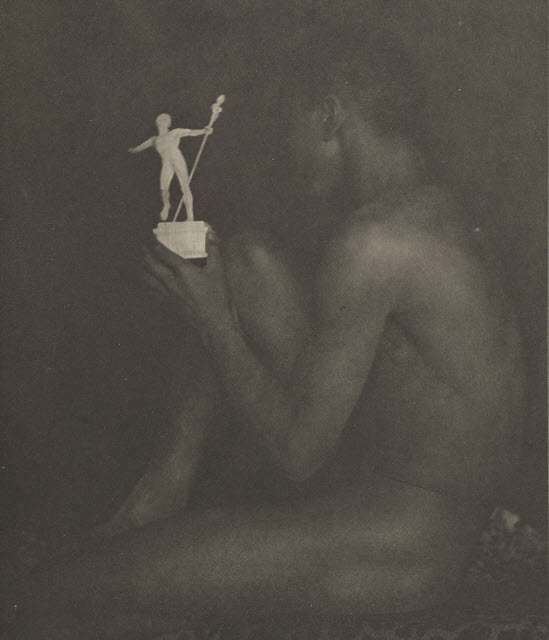

In many respects, it was daring of Day to portray a Black man as a powerful leader during a period when lynching in the United States was at its height. Scholar Shawn Michelle Smith points out that, by celebrating the Black male body, Day challenged the Eurocentric measure of ideal beauty that placed the Greek body at its pinnacle. Smith writes that Day instilled a sense of homoerotic longing in his photographs of Skeete, as he did in other images, such as Ebony and Ivory (fig-2), which features the Black male model J. R. Carter.2 At the same time, Day’s photographs of Skeete, with their emphasis on the model’s body and an imagined concept of an African leader, are problematic in that they perpetuate a pattern of white artists exoticizing and eroticizing people of color.

Day was one of the rare pictorialist photographers to highlight the male nude. Pictorialism was a loosely linked international aesthetic movement of photographers who sought to promote their work as an art form and a mode of personal expression from around 1885 to 1915. A pictorialist style was frequently characterized by soft focus, dramatic lighting and shading, and romanticized subject matter. It was rare for a pictorialist to highlight the male nude. Day advocated strongly for photography as an art form through his images, his articles in Camera Work, and his exhibitions in the United States and Europe. In 1895, he was elected into the British pictorialist salon, The Linked Ring.

An Ethiopian Chief was reproduced in photographic journals such as the February 1901 issue of The Photogram and was widely exhibited in the U.S. and London between 1897 and 1900. Day also used the same photograph as the centerpiece of his triptych Armageddon, in which the Ethiopian leader comes to stand as a symbol of justice between representations of sin and virtue.

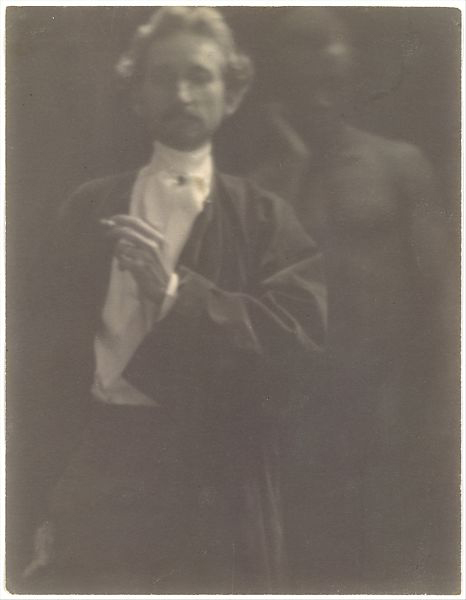

In 1902 Clarence White created a photographic portrait of Day (fig-3) with a nude, dark skinned man standing in the shadows behind him; this man may be Skeete. Skeete passed away in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1945.

- Carolyn Peter, J. Paul Getty Museum, Department of Photographs

For further information about Day, Skeete, and this series see:

Fanning, Patricia J. Through An Uncommon Lens: The Life and Photography of F. Holland Day. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2008.

Jussim, Estelle. “F. Holland Day’s ‘Nubians.’” History of Photography. 7, no. 2 (April-June 1983): 131-42.

Michaels, Barbara L. “New Light on F. Holland Day’s Photographs of African Americans.” History of Photography. 18, No. 4 (Winter 1994): 334-347.

Smith, Shawn Michelle. “The Politics of Pictorialism: Another Look at F. Holland Day.” In At the Edge of Sight: Photography and the Unseen, by Shawn Michelle Smith. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013. 39-71.

-

Barbara L. Michaels, “New Light on F. Holland Day’s Photographs of African Americans,” History of Photography 18 (Winter 1994) 336. ↩︎

-

Shawn Michelle Smith, “The Politics of Pictorialism: Another Look at F. Holland Day,” in At the Edge of Sight: Photography and the Unseen, by Shawn Michelle Smith (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 55, 62-69. ↩︎