More than half a century before the Cubists purportedly set off an artistic revolution by adding collaged elements to their canvases, Victorian women were flouting artistic and social conventions by cutting up pictures and pasting them into elaborate scenes of their own creation. In the process, these women threw the meaning of photography and their own societal roles into question. The Getty has several strong examples of albums filled with such photocollages.

Behind this unassuming cover are thirty-six elaborate photocollage compositions(fig-1). Unfortunately, we don’t know the name of the artist who made them. Most Victorian collagists saw little reason to sign their names to their works. As private objects, the albums remained at home and were not highly valued as works of art. Their makers would never have expected them to end up in a museum.

The albums were created almost exclusively by women of the British “Upper Ten Thousand”—the aristocracy and the landed gentry—England’s landowning class in the second half of the nineteenth century. Making such albums was deemed an acceptable pastime akin to needlework, learning a foreign language, singing, or playing a musical instrument. Here a woman could display her wit and artistic talents within domestic parameters.

When not entertaining company, a woman might spend idle hours in the drawing room of her country home, snipping up photographic portraits of family, friends, and celebrities and mounting them in amusing and sometimes fantastical new settings. She drew or painted the scenes using, ink, wash, and watercolor. In one scene from this album, a young woman plays a game of cards at a table (fig-2). If one were to switch out the cards for some photographs, a pair of scissors/paper knife, a pen, an ink well, and a pot of glue, this scene could easily depict a session of photocollaging.

A Victorian collagist did not concern herself with ensuring that the photographs seamlessly blended into their drawn settings. By placing the images in new contexts, she unapologetically undermined photography’s reputation for being truthful. The collagist dictated who would inhabit her scenes and how they would be depicted. She controlled the world she created, while also poking fun at individuals and society.

A young aristocratic woman’s lessons and activities revolved around the important mission of finding a well-suited husband of high social status. A photocollage album served as a portfolio that an eligible woman could show a suitor. It displayed her wit, artistic talents, and place in society through the circle of friends and acquaintances pasted inside. An album also offered a young man and woman an excuse to sit close to each other on the sofa as they turned the pages of the album making flirtation that much easier. One could imagine that the woman standing in the threshold in the scene at the right above is about to greet her gentleman caller and suggest that they look at one of her albums lying on the ground to his left (fig-3).

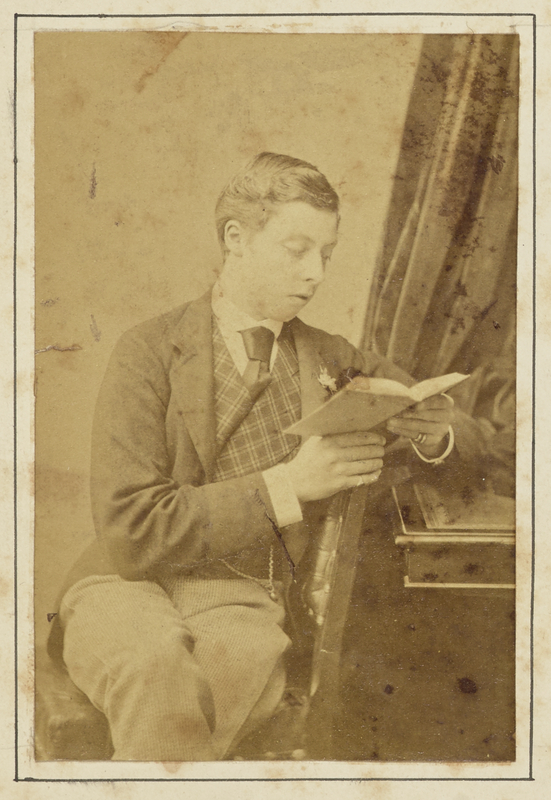

Collagists took their photographic materials primarily from cartes-de-visite—small portraits mounted on heavy cardstock measuring 3 1/2 x 2 1/8 inches, roughly the size of playing cards (fig-4). Patented by André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri in 1854, the carte-de-visite was easily and inexpensively printed. By 1860, cartomania had taken hold and it became customary to exchange cartes-de-visite on social calls to friends. Introduced in 1866, cabinet cards also became a widely used material for photocollage. Measuring 61/2 x 41/4 inches, they offered slightly larger images and might portray bigger groups of people with which the photocollagist could work.

Some photocollagists travelled in social circles that included royalty, political leaders, and military heroes. Thus, they would have exchanged cartes-de-visite or cabinet cards with these well-known people when they gathered at social occasions. However, many other Victorians purchased cards of the royal family, actors, and political leaders despite not knowing them personally. A woman’s collection of cartes-de-visite visually displayed her social circle and favorite celebrities. Specially manufactured albums came with slots to easily house them. An album could intermix pages of cartes-de-visite with full-page collages. Collagists sometimes also painted ornamentation directly onto the slotted pages that held the cartes-de-visite.

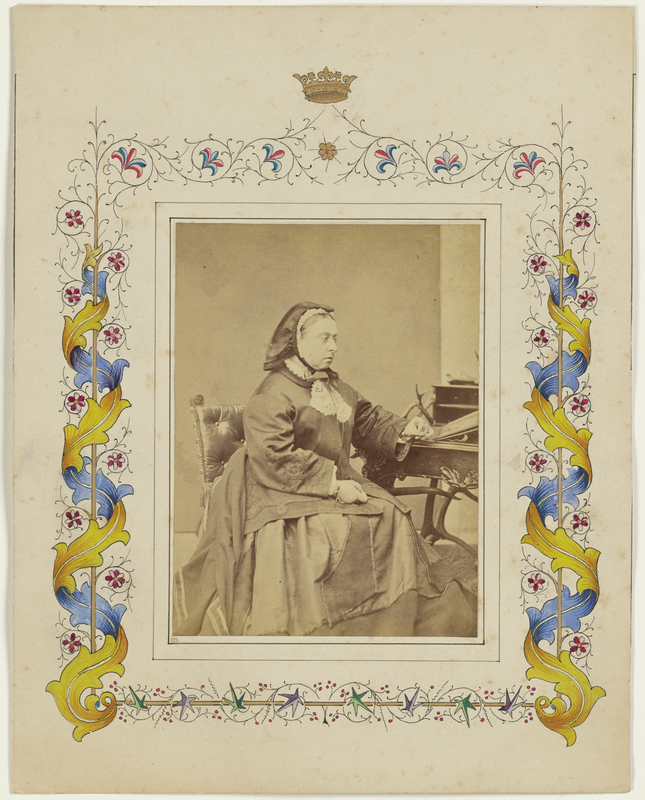

In this album, the photocollagist did not include any mounted cartes-de-visite or cabinet cards. Rather, she removed them from their backings and cut them down to her specific needs. On one page, she added a watercolor decorative border around a full, but unmounted cabinet card of Queen Victoria (fig-5) and on another, she created an elaborate architectural design to present some of the queen’s children.

Victorian photocollagists chose settings and activities from their own privileged lives. A costume ball, a trip to the pet shop, a leisurely hour in a bookshop or library, a game of pool, and a carriage ride are some of the subjects in this album. The artist did however also venture further from home to depict a scene in Japan(fig-6), the Wild West, and even Khartoum, places to which she likely never traveled. The fashion of the day weaves its way throughout the photocollages. Thus, these albums extend beyond a personal diary of one woman’s life to document a broader idea of upper-class British life and culture.

By mixing mechanically produced photographs with drawn and painted images, Victorian collagists created something entirely new. Anticipating a time when photography would be approached more fluidly, they played with scale and integrated multiple perspectives by including photographic imagery of varied proportions taken from different angles. They also added color with ink and watercolor in an era when photographic technology could not yet reproduce such hues.

These artists questioned the accepted view that photography told the truth by integrating cut-out pictures into imagined scenes or montaging several portraits of one person into a composition. They didn’t worry about the awkward integration of photographs into their collages. Instead, they relied on drawn elements to help unify the composition. They invited viewers to suspend disbelief.

Working within the constraints of societal conventions, these upper-class women collagists strengthened social ties, forged romances, and humorously entertained their circles of friends and family. At the same time, they gained a sense of empowerment from their compositions by creatively and subversively conveying their opinions and feelings about their world.

- Carolyn Peter, J. Paul Getty Museum, Department of Photographs

For More Information:

Geoffrey Batchen, Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance, (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum/Princeton Architectural Press, 2004)

Ann Bermingham, Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art (Yale University Press, 2000)

Elizabeth Siegel, ed. Playing with Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2009)

Morgan Hamon, former graduate intern in the Department of Photographs, J. Paul Getty Museum talks about the anonymous photocollage album featured in this exhibition. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=10156221285520097

“Radical Whimsy: Victorian Women and the Art of Photocollage” published online in 2021 via Google Arts & Culture, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/KAUhrgTXuuGwZg