More than half a century before the Cubists purportedly set off an artistic revolution by adding collaged elements to their canvases, Victorian women were flouting artistic and social conventions by cutting up pictures and pasting them into elaborate scenes of their own creation. In the process, these women threw the meaning of photography and their own societal roles into question.

Victorian photocollage albums were created in the second half of the nineteenth century almost exclusively by women of the British “Upper Ten Thousand”—the aristocracy and the landed gentry—England’s landowning class. Making such albums was deemed an acceptable pastime akin to needlework, learning a foreign language, singing, or playing a musical instrument. Here a woman could display her wit and artistic talents within domestic parameters. Most of the photocollagists remain unknown. They saw little reason to sign their names to their works. As private objects, the albums remained at home and were not highly valued as works of art. Their makers would never have expected them to end up in a museum.

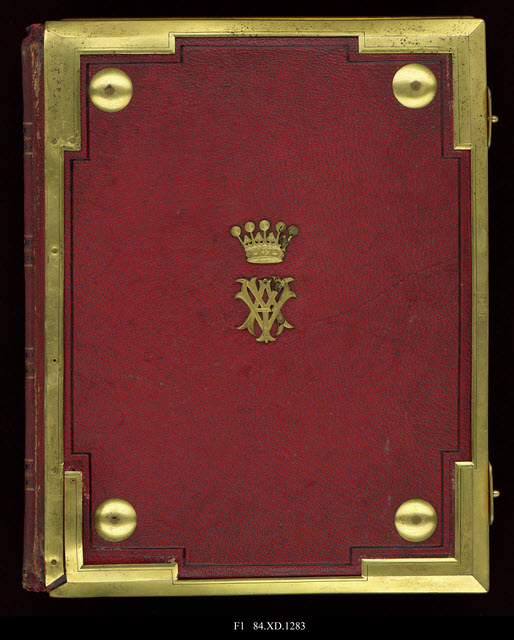

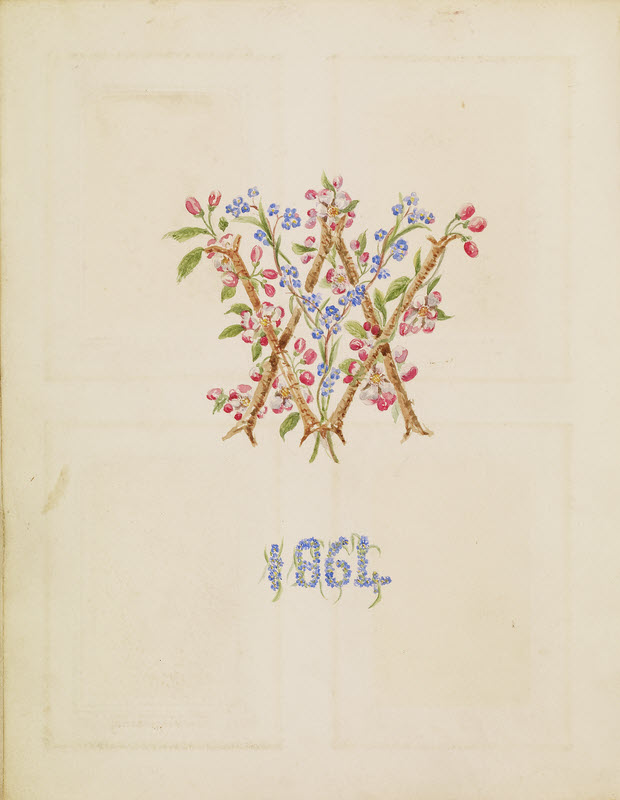

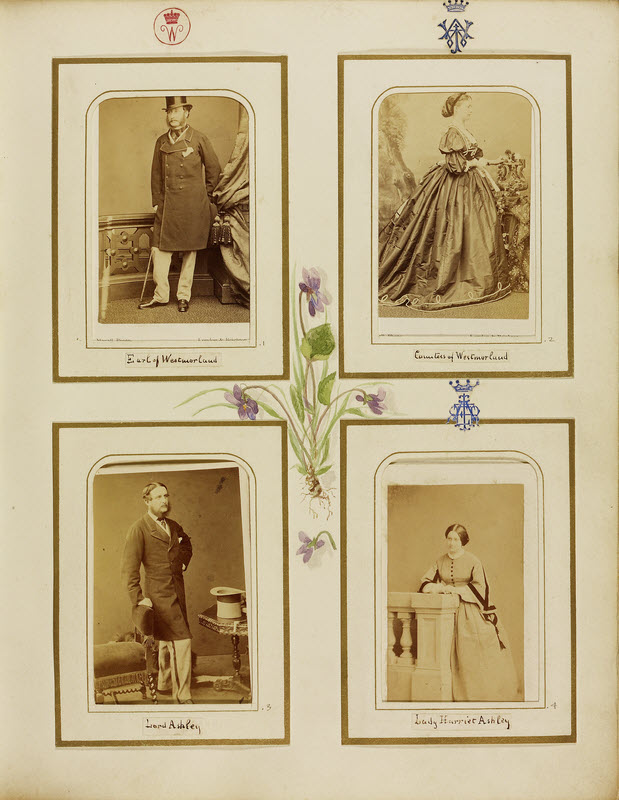

This album was given the title The Westmorland Album at some point in its life because the portraits of the Earl and Countess of Westmorland appear at the top of its first page of photographs (fig. 4). However, the likely owner and compiler was recently identified by curators at the Art Institute of Chicago. The initials “VAY” found on the well-preserved red leather album cover (figs. 1-2) and in the watercolor design on the opening page suggest that Victoria Alexandrina Hare Anderson-Pelham, Countess of Yarborough (also known as Lady Yarborough, 1840-1927), assembled the album and made some of the compositions. Countess Yarborough’s niece Eva Macdonald (1846/50-1930) also created at least two of the collages. Thus, this album presents a rare instance where the compiler and artist, for at least some of the photocollages, has been identified.

The Countess of Yarborough and her husband, the Earl of Yarborough (also known as Lord Yarborough, 1835-1875) are depicted in several photographs and collages in the album (fig. 3). She was the goddaughter and namesake of Queen Victoria and therefore traveled in the circles of royalty and aristocrats. Her collection of cartes-de-visite visually display her family and broader social circle while also documenting social events that took place in and around her in Lincolnshire country estate, Brocklesby Park.

As in other photocollage albums, the photographic material used in this album came primarily from cartes-de-visite. Patented by André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri in 1854, the carte-de-visite was easily and inexpensively printed (84.XD.1157.2179). By the 1860s, cartomania had taken hold. It became customary to exchange cartes-de-visite when calling upon friends. These small portraits measure 3 1/2 x 2 1/8 inches, about the size of a playing card. It is not known whether these artists removed the photographs from the thick cardstock on which they had been mounted or obtained unmounted prints from the photographer. Even people who were not part of the royal circle collected cards of the royal family, actors, and politicians. So, it is not uncommon to find some the mass-produced images of the royal family or other celebrities in multiple photocollage albums.

The Westmorland Album displays a myriad of ways that a photocollagist could use her artistic skills to highlight and augment the photographic images. Some pages present unaltered cartes-de-visite; special manufactured album pages came with slots where the cartes-de-visite could be inserted. The Countess of Yarborough, Eva Macdonald, or another collaborator often added painted floral ornamentation to the center of these pages (fig. 4).

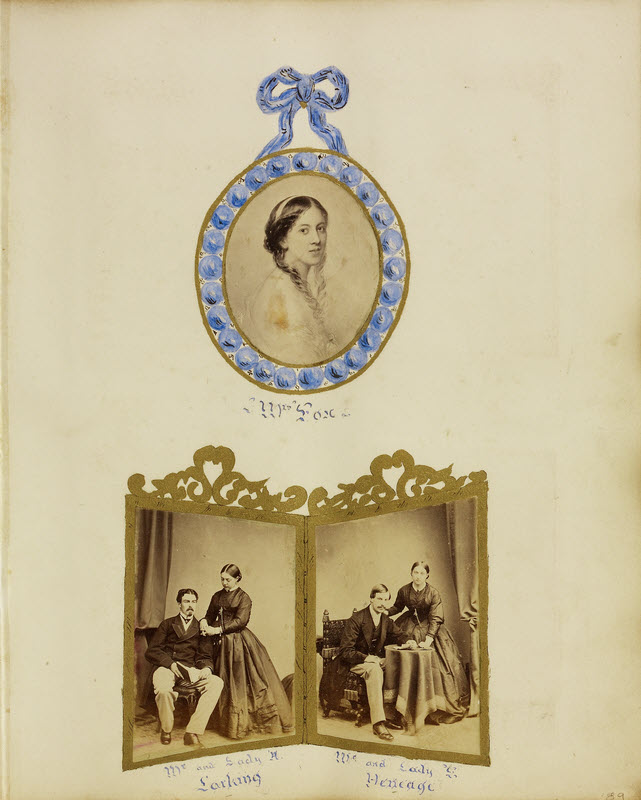

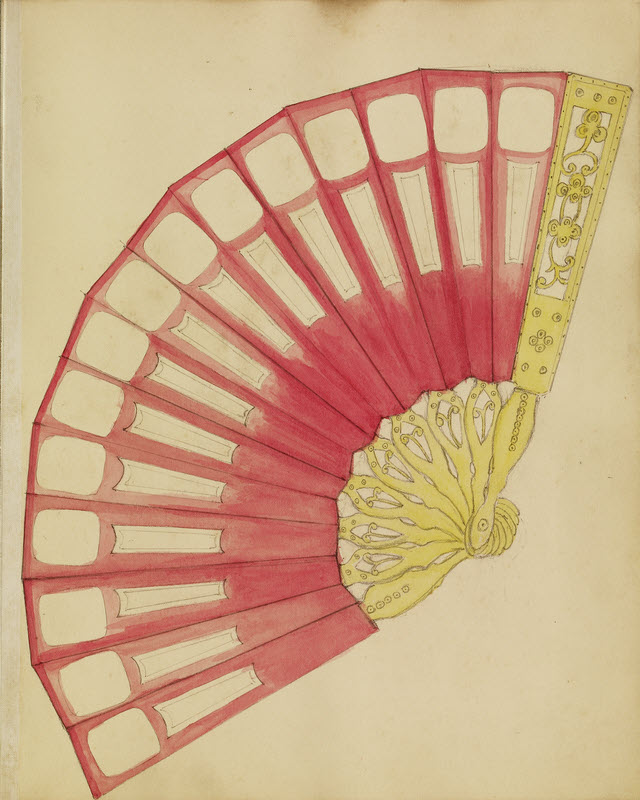

On other pages, the artist painted decorative frames around photographic images or created a montage of different photograph in a diamond or flower shape (fig. 5)(84.XD.1283.69, .87, .104, .110, .154) And in other instances, the photocollagist intermixed cut sections of a photographs into an elaborate full-page scene. The Westmoreland Album also includes examples of unfinished compositions awaiting further design as well as the insertion of photographs (fig. 6).

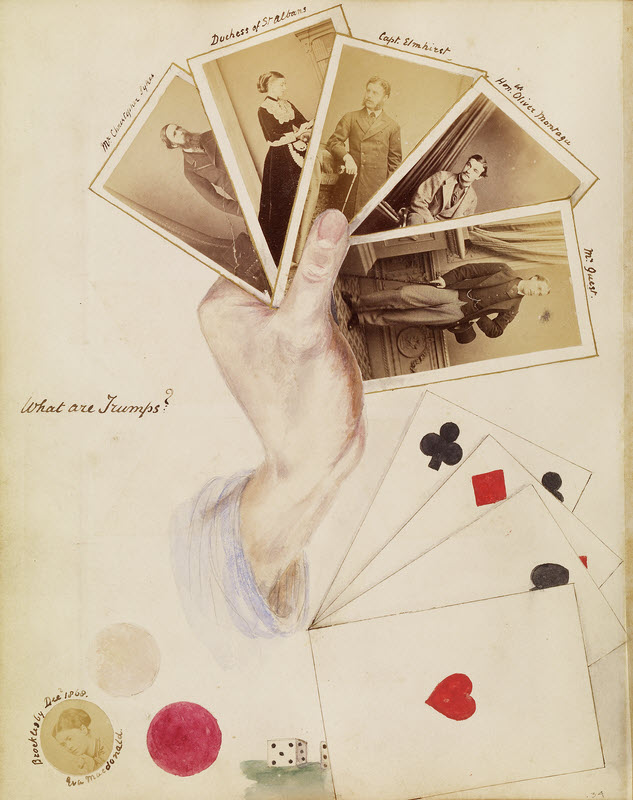

Two collages in The Westmorland Album bear the signature of Eva Macdonald. These compositions commemorate the people Macdonald encountered and the social events that took place during her visits to her aunt and uncle’s country estate (fig. 7) (84.XD.1283.34). In this composition, five cartes-de-visite are fanned out like a hand of playing cards. Macdonald’s photographic likeness is found in the form of a gambling chip at the bottom left of the collage. Her signature and the date the drawing was made encircle the portrait (fig. 8).

The people portrayed were part of the Earl and Countess of Yarborough’s social circle—Christopher Sykes (an English politician) (1831-1898), Sybil Mary (née Grey), Duchess of St Albans (1848-1871), Captain Elmhirst (possibly William Augustus Elmhirst), the Honorable Oliver Montagu (1844-1893), and Montague John Guest (an English politician) (1839-1909). Through Macdonald’s imagination, they become pieces in a game of gambling, flirtation, and social status. In the minute circular portrait of Macdonald at bottom left, she holds something rectangular in her hand. It might be a stack of playing cards suggesting that Macdonald was playing the role of dealer.

In Macdonald’s second signed photocollage (84.XD.1283.161) she documented an 1870 ball at Brocklesby Park including the names of many of those in attendance. She married her first husband, Henry Algernon Langham, in 1873; he died the next year. She went on to marry her second husband, the Scotsman Robert William Napier of Magdala, 2nd Baron (1845-1921), in 1885. Perhaps her artistic talents, honed early on in her photocollage work, played a role in both her courtships. She later exhibited paintings at the Royal Academy’s annual exhibitions in 1889, 1896, and 1898 and published novels and short stories, such as Fiona (1909), How She Played the Game (1910), and Half a Lie (1916), under her married name, Lady Napier.

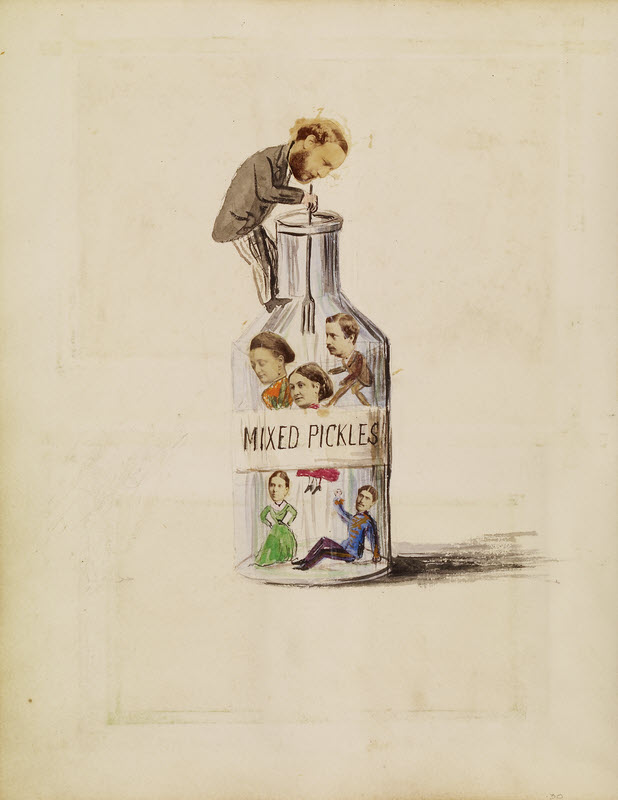

A Victorian collagist did not concern herself with ensuring that the photographs seamlessly blended into their drawn settings. By placing the images in new contexts, she unapologetically undermined photography’s reputation for being truthful. The collagist dictated who would inhabit her scenes and how they would be depicted. She controlled the world she created, while also poking fun at individuals and society.

By mixing mechanically produced photographs with drawn and painted images, Victorian collagists created something entirely new. Anticipating a time when photography would be approached more fluidly, they played with scale and integrated multiple perspectives by including photographic imagery of varied proportions taken from different angles. They also added color with ink and watercolor in an era when photographic technology could not yet reproduce such hues.

These artists questioned the accepted view that photography told the truth by integrating cut-out pictures into imagined scenes or montaging several portraits of one person into a composition. They didn’t worry about the awkward integration of photographs into their collages. Instead, they relied on drawn elements to help unify the composition. They invited viewers to suspend disbelief.

Working within the constraints of societal conventions, these upper-class women collagists strengthened social ties, forged romances, and humorously entertained their circles of friends and family. At the same time, they gained a sense of empowerment from their compositions by creatively and subversively conveying their opinions and feelings about their world.

- Carolyn Peter, J. Paul Getty Museum, Department of Photographs

For Further Information:

Geoffrey Batchen, Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance, (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum/Princeton Architectural Press, 2004)

Ann Bermingham, Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art (Yale University Press, 2000)

Elizabeth Siegel, ed. Playing with Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2009)

Morgan Hamon, former graduate intern in the Department of Photographs, J. Paul Getty Museum talks about another anonymous Victorian photocollage album in the Getty Collection. [https://www.facebook.com/gettymuseum/videos/10156221285520097/

“Radical Whimsy: Victorian Women and the Art of Photocollage” published online in 2021 via Google Arts & Culture, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/KAUhrgTXuuGwZg